READERS GUIDE

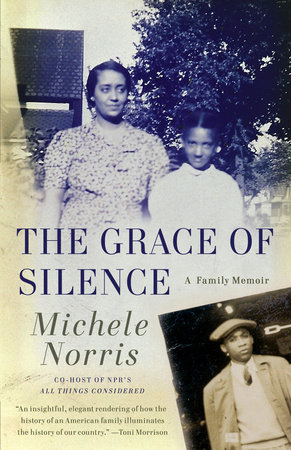

The questions, discussion topics, and reading suggestions that follow are intended to enhance your reading group’s discussion of The Grace of Silence, Michele Norris’s deeply personal memoir.Introduction

“Powerful and heartbreaking. . . . [Norris] explores race within her family history while tracing its complex legacy in the United States.” –San Francisco ChronicleWhile exploring the hidden conversation on race unfolding throughout America in the wake of President Obama’s election, Michele Norris discovered that there were painful secrets within her own family that had been willfully withheld. These revelations—from her father’s shooting by a Birmingham police officer to her maternal grandmother’s job as an itinerant Aunt Jemima in the Midwest—inspired a bracing journey into her family’s past, from her childhood home in Minneapolis to her ancestral roots in the Deep South.

The result is a rich and extraordinary family memoir—filled with stories that elegantly explore the power of silence and secrets—that boldly examines racial legacy and what it means to be an American.

Questions and Topics for Discussion

1. Michele Norris discovered family secrets because elders in her family started divulging stories in the wake of Barack Obama’s election. What were conversations about race like during the 2008 election? Was there a difference between public and private discussions? Have those conversations changed in the last two years?

2. How did family secrets affect life in the Norris home? What does Norris mean when she says she was “shaped by the weight of silence”? In your own family, have you had the experience of finding out something about a family member that you never knew? Alternatively, have you ever been the keeper of such secrets?

3. In the airport, Norris watches two women misjudge her father as a drunk rather than a very ill man, but chooses not to confront them. How is her decision related to being a “model minority”? Do you understand Norris’s belated desire to be the black girl some white women are conditioned to fear most? What do you think of her statement that “Blacks often feel the dispiriting burden of being perceived willy-nilly as representing an entire race”?

4. While Norris feels certain that the white women’s reaction is informed by race, she cannot be absolutely sure: “Here is the conundrum of racism. You know it’s there, but you can’t prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, how it colors a particular situation.” Have you experienced times when you thought race was a factor but were unable to prove it? What choices have you made to address or ignore the possibility of racist behavior?

5. Norris’s mother and uncle have different perceptions of her grandmother Ione’s work as a traveling Aunt Jemima. While her mother has mixed emotions, her uncle says, “I know a lot of people are ashamed of that image but I am not. . . . She put that costume on and she was a star.” Norris finds a similar range of reactions when she delves into the history of Aunt Jemima. The owner of Mammy’s Cupboard restaurant says, “Sometimes I don’t understand why black folks don’t claim her, because she was theirs first. She’s still theirs, isn’t she?” What’s your answer to that question? What does the Aunt Jemima image mean to you? Does the upgrade to her image destigmatize the logo? What are other examples of complicated images in American commercial life?

6. The Norris family were “block busters” in Minneapolis. Do you live in a community that was or still is segregated by race or class? Why do you think the neighbor who was a displaced person was so unwelcoming to the Norris family?

7. Belvin and Betty Norris were sartorial activists, dressing to impress in all circumstances. Do you understand why? Do you find yourself doing the same thing? Why do you think certain groups put so much emphasis on outward appearances such as clothes or cars?

8. Norris writes that she was deprived of the story of her father’s shooting not only because of family silence, but “because the collective story of the black World War II veteran had been slighted.” Before reading The Grace of Silence, did you know the history of black veterans during and after World War II? What affect do you think this period had on civil rights in America and what does it mean that it is rarely discussed these days, if at all?

9. Why do you think Belvin Norris never talked about his encounter with Birmingham police with his wife or children? Do you think he would have talked about it if asked? How does his silence compare to Betty Norris’s reluctance to talk about her mother’s Aunt Jemima job?

10. While Norris didn’t know the story of her father’s arrest, her cousin had “heard about it from his father during a cautionary ‘never look a cop in the eye’ conversation that black men often have with their teenage sons.” Black communities refer to DWB (driving while black) as shorthand for police profiling. The recent immigration law in Arizona also singles out a particular group. Do you think such profiling is a problem in America? Do you agree with its use in any situation?

11. Why do you think Belvin Norris returned to Birmingham so often with his family despite his violent encounter? Has your family or anyone in it had to exile themselves from a place? Did you or they return to that place, or avoid it completely?

12. Norris makes the point that white officers in Birmingham in the 1940s and ‘50s earned less than what they would make in the mills or the mines. They had to provide their own flashlights and pistols, and they were led by a man—Bull Conner—who was overtly racist. Does knowing more about the officers’ situation affect how we understand their actions?

13. Julia Beaton says to Norris: “I have no white American friends. I just don’t care for them. I just don’t trust them. I have always told my sons and my grandsons not to bring a woman in this house who does not look like me.” What was your reaction to Beaton’s statements? Do you respond differently to her, as an older black woman, than you do to the older white men and women that Norris also interviews? Should we judge her words less harshly than we might a white person saying “I just don’t trust black people”?

14. Aubrey Justice tells Norris that “In some ways it seems like things were better when the races had their own.” Norris reflects, “I wonder whether Justice might not be speaking the truth, at least in part. You can’t visit my grandparents’ neighborhood in Ensley and avoid asking, Did integration work as planned?” Was Birmingham’s black community better off in some ways during segregation? Is that true for other communities? Who is responsible for the changes that have come to neighborhoods like Ensley?

15. Have you lived in a neighborhood or worked in an environment or attended a school that went through the initial stages of integration? What was your experience as the integrator or member of the majority culture?

16. Davis Shull laments, “Nowadays everything is racist. No matter what you say. You can’t tell the truth without being racist. You can’t say anything.” Political correctness is an enormous focus in American life. Does it leave any room for real conversations about race? What role does such correctness play in stories like Shirley Sherrod’s, and also in situations like Joe Biden describing Obama as “the first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy”? Was Attorney General Eric Holder right when he said, “Though this nation has proudly thought of itself as an ethnic melting pot, in things racial we have always been and continue to be, in too many ways, essentially a nation of cowards”? Do you understand what Holder meant when he suggested that “to get to the heart of this country one must examine its racial soul”?

17. There is often the assumption that white people are responsible for the persistence of racism. There is less emphasis, Norris writes, on exploring “the legacy of distrust black parents pass on to their children.” Is there an imbalance in the way we see the legacies of race in America?

18. Take some time to discuss racial stereotypes. What characteristics (lazy, driven, violent, studious, etc.) are attached to certain racial and religious groups: blacks, Jews, Muslims, Asians, Latinos, whites, etc.? Do different groups hold the same images of each other—would a white man see the same stereotypes as a black woman or a Latino teenager? Consider as well the role of race and gender in those stereotypes.

19. Norris asks a powerful question at the end of The Grace of Silence: “What’s been more corrosive to the dialogue on race in America over the last half century or so, things said or unsaid?” Discuss your responses.

20. “All the talk of a postracial American betrays an all too glib eagerness to put in remission a four-hundred-year-old cancerous social disease. We can’t let it rest until we attend to its symptoms in ourselves and others.” Norris’s work demands that we look at our own lives and consider how honest we are with ourselves and how open we are with each other. Are you able to talk about race with friends? Are you honest with yourselves about your own prejudices? What legacies have your families and communities bequeathed to you? What have you passed or want to pass on to your children? Have you ever been accused of being a racist? Why does that label carry such stigma?

21. The question at the heart of Norris’s memoir is “How well do you know the people who raised you?” Carry this question home with you and, as Norris states, “take the bold step and say: Tell me more about yourself.” Stay at the table even if the conversation is difficult, and prepare yourself to listen. “There is grace in silence, and power to be had from listening to that which, more often than not, was left unsaid.”

(For a complete list of available reading group guides, and to sign up for the Reading Group Center enewsletter, visit www.readinggroupcenter.com)