READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

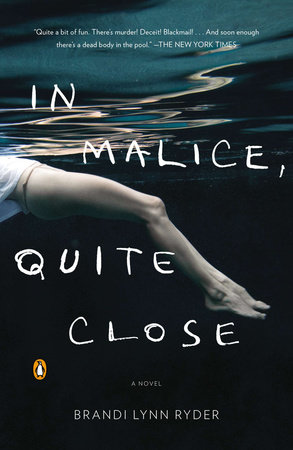

A middle-aged European aristocrat, his sexuality skewed and tortured by a tragic past, comes to America and becomes infatuated with a teenage girl, who fantasizes about escape from her own drab, soul-destroying existence. Seeing his chance, he abducts her, and the two embark on an odyssey fraught with passion and deception that leads at last to tragic death. Lolita? No; it’s the audaciously brilliant debut novel by Brandi Lynn Ryder In Malice, Quite Close, and those who reasonably assumed that Nabokov had said the last important words about international, intergenerational seduction are about to make the discovery that they were mistaken.

In Malice, Quite Close draws readers into the aesthetically refined but emotionally fractured world of Tristan Leandre Jourdain Mourault III. A man of wealth and taste (the Rolling Stones’s “Sympathy for the Devil” is only the most obvious of the novel’s profusion of eclectic cultural allusions), Tristan has inherited a priceless collection of Impressionist paintings, but, as he confesses to the reader early on, he prefers his art living. The piece he most yearns to add to his collection is Karen Miller, a precocious but naïve fifteen-year-old girl from San Francisco, whom he decides to “liberate” from her shabby home and sexually abusive father. With consummate cunning, he lures Karen into running away with him, leaving evidence to suggest that the girl has been murdered. After breaking Karen’s will to escape, Tristan renames her Gisèle and the two settle in New York as father and daughter.

But Tristan is both predator and prey. A blackmailer sends photographs of him with Karen in San Francisco, and the two are forced to flee to the exclusive, idyllic artists’ community of Devon, Washington. There, all appears to be opulence and ease. Gisèle marries and has a daughter, Nicola, and it seems for many years as if Tristan will escape judgment. His tracks, however, are imperfectly covered. The man on whom he most depends to guard his past, the artist-philosopher Robin Dresden, proves anything but trustworthy. Karen’s long lost sister Amanda also appears on the scene, and both she and Nicola start asking uncomfortable questions. A cache of nude paintings of Gisèle unexpectedly surfaces, and the web of suspicion grows ever broader: What is Gisèle’s real identity? Who is Nicola’s actual father? And who has painted the exquisite, enchanting paintings that both reveal Gisèle and heighten the mystery that surrounds her? As the questions proliferate, Tristan descends into the kind of desperation that can lead to murder.

An astonishing work that blends the suspense of a classic whodunit, the insight of a psychological thriller, and the philosophical richness of a literary masterpiece, In Malice, Quite Close is a gripping, unforgettable book that remains with the reader long after its last mystery has been disclosed.

ABOUT BRANDI LYNN RYDER

A native of Sonora, California, and a summa cum laude graduate of San Jose State University, Brandi Lynn Ryder has been telling stories for as long as she can remember. In Malice, Quite Close, which was a finalist for the 2009 Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award, is her first novel. She lives in Napa Valley, California.

A CONVERSATION WITH BRANDI LYNN RYDER

Q. Like your character Karen Miller, you dreamed of being a writer since childhood. What other traits of Karen Miller/Gisèle Mourault do you see in yourself?

I’m often asked if my characters and stories are autobiographical. Given the nature of some of my characters, I hesitate to go down that particular rabbit hole! I will say that I can relate very much to Gisèle’s search for identity. She is as trapped in the role of Karen Miller as she later is as Gisèle Mourault. She moves from the dysfunction of her family to being Tristan’s prized objet d’art. While my circumstances were certainly different, I was something of a chameleon as a teenager; I’d slip into various guises to suit my surroundings. Eventually, I was able to pinpoint this as a fear of self-revelation, a need to establish “identity” through the affirmation of others. Like Gisèle, my redemption was art. In it, I found honesty and authenticity to be the only signposts—pivotal to any true sense of self or deep relationship to others. Throughout the novel we see Gisèle only as she is defined by those around her, which is why she’s given no point of view in the novel. But I think she was on the brink of the self-definition she sought in her art, that she would have continued down this path and ultimately succeeded. By the end, the truth has become something for which she’s willing to face great risk and sacrifice.

Q. You took your novel’s title from a Rimbaud poem that also serves as the book’s epigraph. How and why did you choose it?

I love the language and have long admired the emotional charge of Rimbaud’s work. There is a lot of courage in his poetry, a raw honesty. In “First Evening,” one finds an unabashedly objectifying seduction scene. There is a clear disparity between the speaker and the young woman, the object of his desire: probably in age, certainly in power and experience. He chronicles the effects of his actions on her as one might analyze an insect under a microscope. Combined with this calculated remove, I find his amused, patronizing tone chilling and very well suited to the themes of the book.

Q. Your title was interesting in that much of the evil in your novel seems to emerge from something other than malice, be it eroticism, selfishness, or some kind of cowardice. Are you suggesting that we need a more complex understanding of the word “malice” than we typically use?

That’s a great question. Even in the translation from French, “malice” is a rather controversial interpretation of Rimbaud’smalinement, but I personally love this choice; I feel A. S. Kline masterfully captured the true spirit of the poem. In common usage, “malice” is typically used to describe evil intent, and in legal terms an “absence of malice” lessens the offense. One of the things I’d hope to accomplish with this novel is to encourage readers to look hard at the intent of each of the characters and the apologies they offer for their crimes and decide for themselves. I suppose I am suggesting a deepening and expansion of this word, of the way we weigh motivation and responsibility. It seems to me there is definite malice in repeatedly—and knowingly—harming others for one’s own reasons, whether sexually motivated or simply as a result of cowardice. Selfishness is unconsciously malicious. However, I use the actual word only once in the novel and in relation to only one character. It’s an intentional marker—a clue for close readers.

Q. Although the debt is paid off with interest later in the novel, the early scenes of In Malice, Quite Close owe a great deal to Nabokov’s Lolita. How did you keep your novel from standing too much in Nabokov’s shadow?

I’m afraid I’m bound to be credited with either great audacity or great courage, and more likely the former. The theme, even semantically—a “Lolita affair”—belongs to Nabokov. To be perfectly honest, I had not read Lolita when I wrote the first draft ofIn Malice. I’d read and loved much of his other work, and of course had a cultural awareness of Lolita, but I was not directly influenced by it. When I’d finished this novel, I did decide to read Lolita because I knew the comparison was inevitable. And at some point, I toyed with decreasing the similarity by making Tristan American. Unfortunately, he completely refused to cooperate. He is quintessentially French in his sensibilities and by then his accent had permeated my brain. Karen’s age, too, was vital to her character. Her youth and naïveté make her uniquely vulnerable to Tristan. She is a “work in progress.” Suffice to say, I feel the Lolita affair in this novel is a small element of the larger story and themes and I hope any similarity will be seen as a respectful homage. My intent was never to rival Nabokov or attempt to retell a story so brilliantly told. I do feel the entire field of human experience should remain open to writers, as indeed I imagine there are painters still intent on capturing the light and that Monet would heartily approve.

Q. In your novel, Robin Dresden tells an interviewer that he doesn’t mind that critics look for meaning in his work; indeed, he hopes they find it (p. 123). How do you feel about this when it comes to your own work?

For me, everything has meaning. That is the great thrill—and great challenge—of being alive. And certainly the great thrill and challenge of art. That said, I think the very worst thing an artist can do is to dictate the meaning of their work to others! I can’t tell you how many songs have been ruined for me by a rather prosaic explanation of the lyrics by the songwriter. Art lives in the mind of the creator, but equally in the minds of those who perceive it. I expect this story will have as many meanings as it does readers.

Q. How does your own philosophy of art compare with Robin’s?

I think they’re very similar, though I’m still learning from him. Put simply, and as he states in the novel: “Art is why.” Most of our time and energy is concerned with the means of life, the “how.” But art is the why. I don’t agree with those who claim art is a privilege. Even in the most impoverished societies, there are beautiful traditions of storytelling, song, dance, visual arts. Art is essential, a dialogue, an outcry, a celebration, both a window and a mirror into history and culture. In creating art we engage the magical, inexplicable fact of being.

Q. Gisèle tells Tristan that she does not want to spend her whole life being pleased (p. 216). What’s so bad about feeling good?

Nothing! But I think this revelation is, for Gisele, the signal of her maturity, her entry into adulthood. There is great pleasure in giving. Even great power. Tristan is happy to keep Gisèle on a shelf and take her down when he wishes, to admire and care for her, to polish her and put her away again. She doesn’t want to be “kept.” She wants to participate in the relationship, to give back. Gisèle’s most satisfying relationships in the book are all giving relationships—with her daughter, her younger sister, her art. It’s something I like about her. She knows, even at a young age, that being human is something more than being a receptacle, even if it’s a receptacle of pleasure.

Q. It seems that art ought to stimulate people toward more humane sensibilities. For characters like Tristan, Robin, and Marc, however, beauty and artistry seem to be corrupting influences, and artistic temperament becomes an excuse for cruelty. What role do you see art playing in your own experience?

I have to disagree with the assertion that art “ought” to do anything, that it ought to deliver a message of some kind. In my opinion, art is at its worst when heavy-handed and didactic. If inspired, art inspires. It is going to inspire different things in different people. Beauty, certainly, has tempted people to destruction and inspired terrible things. That’s why it is such a fabulous theme for literature.

In my novel, it is not art or beauty that corrupts but a character’s drive to control, “own,” or otherwise bastardize beauty and artistry that leads to corruption. The artistic process is a freeing one and the act of creating is an inherently positive force, yet I think there is a dissonance between the intangible process of creating art and the tangible product of the art itself. Unfortunately, where there is a product, there will be those who wish to control it. My novel creates a situation in which a human becomes, at least to one character, a work of art. Others forge, steal, manipulate, and murder—each in an ego-driven attempt to control something that is ultimately uncontrollable

In my experience, art is about the loss of ego. Any artist deeply engaged in his or her work has no sense of “self.” Petty and even pressing concerns disappear, time is altered, perception is entirely focused on something other than oneself. Paradoxically, I’m never more “myself” than when writing. Feeling the weight of my first finished manuscript represented for me the weight of years of experience and yet it freed me from the weight of those years too. While my characters struggle with very human limitations and temptations, I hope to always to present art as the “higher road,” the path to self-awareness. Again, the process and the product are very different things and I find this chasm fascinating to explore.

Q. Your descriptions of the Gisèle paintings were some of the most spectacular passages in your book. What paintings did you have in mind when you wrote these descriptions?

Thank you. To be honest, I had no “real-world” inspiration for the Gisèle paintings. I just saw them as I felt the painter would see herself: fragmented and abstract, searching, unflinching, critical. Self as object. To refer back to the Rimbaud poem and the speaker’s analytical remove as he studies the object of his desire—Gisèle studies herself with this analytical remove. She has been all her life an object of male desire; in her art she reenacts this objectification. And I like to feel that she reclaims herself in the process.

Q. The setting of Devon, Washington, is captivatingly rendered—an Eden with, alas, more than one serpent. What real-life places did you draw upon to create your flawed artist’s Shangri-La?

I draw a lot of inspiration from nature and knew the backdrop had to be the Pacific Northwest. It’s nature on a grand scale—wild, raw, utterly beautiful—and the perfect ironic counterpart to all the human attempts in the novel to harness and cultivate the beauty that one finds in Devon. I suppose it’s evident even from the name that I was inspired by England and the charm of the English village, which always seems to hide so much behind its quaint facade. Closer to home, I was very influenced by the lovely town of Carmel in my home state of California, which I mention in the novel and where I’ve been fortunate enough to spend a lot of time. And yes, the galleries there nearly outnumber the residents!

Q. One of the many subtle touches of In Malice, Quite Close is that the chapter titles are taken from paintings by the great Impressionist masters. What effect were you attempting to achieve with this device?

The intent was to bring Tristan’s collection—which is almost a character in its own right—to life for readers. Like many people, I have an ongoing love affair with the Impressionists. The works are exquisite and the titles often evocative. It is a vital aspect of Tristan’s character that he’s grown up surrounded by this great celebration of beauty on the walls. The aesthetic entitlement he feels, not to mention ownership over such a collection, is a thing most of us cannot imagine. There is an online “gallery” of the works on my website and I hope readers will go and experience a bit of Tristan’s world for themselves.

Q. You’ve said that one of your muses is your cat—an attribution that may surprise writers whose cats mostly play with the wires of their word processors and demand to be fed. Care to comment on your feline inspiration?

Well, most of my writing is done with my laptop perched precariously on my knees while Murphy occupies my lap and flourishes his tail in my face, so I absolutely identify with the frustrations! But quite simply, my cat inspires me. He’s sixteen now and has overseen most of my serious writing—all the drafts and revisions and endless stabs at finding the perfect turn of phrase. He’s remarkably verbal and talks me through the downtimes. He’s been known to take a bite out of a manuscript that deserved it. And he is simply a living study of grace, elegance, and self-possession. Mark Twain said it best, “If man could be crossed with the cat, it would improve the man but deteriorate the cat.” I’m offered proof of this daily, but Murphy’s remarkably tolerant and good-natured about it.

Q. Word has it that your next novel will be taking us back to Devon. Might you offer a bit of a preview?

I’d love to! The next book is tentatively titled Like a Guilty Thing, and is taken from Hamlet: “It started, like a guilty thing upon a fearful summons…” In this case, the summons is an invitation to an art exhibition sent anonymously to each of Robin Dresden’s elite group of art students, who are mentioned obliquely in this novel. Previously unknown works of the artistic prodigy Daniel Ekland surface five years after his death and spell out events that each of the students—and Robin—would rather keep secret. Ultimately, the paintings unravel the riddle surrounding Daniel’s mysterious death, in which everyone is more than a little guilty. The novel takes us deeper into Robin Dresden’s world of art and illusion and the dangerous philosophies he passes on to his students, which have effects that even he cannot anticipate.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS