Features

Contemporary Authors on their 1960s research

Discover another era with Sue Monk Kidd, Julia Sweig, and Fiona Davis

This summer we’re taking a look back at the 1960s and how that decade captured the imagination of a nation. We asked some of our popular contemporary authors all about how and why they write about that impactful time.

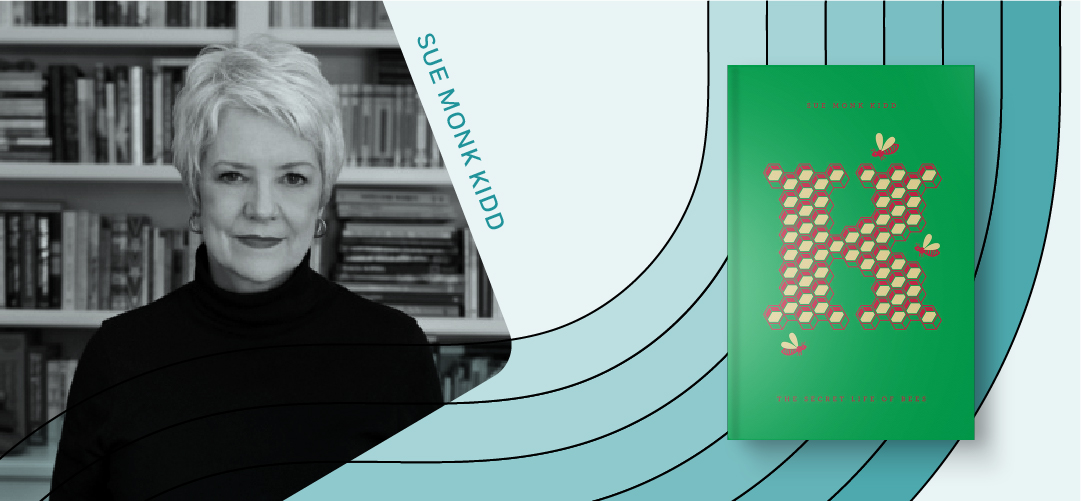

Sue Monk Kidd, author of The Secret Life of Bees

The first time I saw The Secret Life of Bees described as a historical novel I did a double take. Despite the jolt of realizing I’d been alive way back then, I was appreciative of the firsthand experience. My research involved digging out my 1964 high school yearbook. I was a tenth grader with a small skyscraper of a hairdo, an effect we achieved by rolling our hair on Welch’s grape juice cans. That year I wrote a term paper called “My Philosophy of Life,” which I still have as an example of how embarrassing my philosophy was at fifteen. After school, I did my homework while listening to 45 rpm records, primarily Leslie Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me.”

That year, however, was not all about beehive hairdos and class assignments. There was the occasional nuclear bomb drill in which we dived under our desks and nervous talk about the escalating Vietnam War, and a group of feminists who started an organization called NOW, which the ladies at church frowned upon, but which Leslie Gore and I pulled for. Nothing, however, affected me more than the summer of 1964—Freedom Summer, it was called. I watched President Johnson sign the Civil Rights Act on television and Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his “I Have a Dream” speech. I took in hundreds of images of racism, inequality, and white privilege.

When I set out to write my first novel, there was never any question in my mind that it would be set in 1964.

A Q&A with Julia Sweig about her book, Lady Bird Johnson

Did you run into any research dead-ends?

In one of her diary entries, from October 1965, Lady Bird describes an incredible moment at Bethesda Naval Hospital when LBJ dictates his resignation statement to Abe Fortas, then associate justice of the Supreme Court. For LBJ this was a moment of post-operative depression in the aftermath of his gallbladder surgery. The incident went entirely unreported by anyone writing about the Johnson presidency, save for Lady Bird’s account. The Abe Fortas at Yale papers are essentially inaccessible, and the LBJ Library did not have the draft statements. I would have loved to have the chance to hold in my hands the actual statement that LBJ dictated to Fortas, the rationale of which Lady Bird explains but as a die-hard sleuth and archive geek, the inability to see the document did leave me feeling a little… unrequited.. and also makes me wonder if there were other moments that Lady Bird did not recount when LBJ was similarly on the edge of pulling out of the presidency.

Any puzzles you had to solve?

Lady Bird Johnson was herself a puzzle! What made this apparently conventional First Lady tick and how to pull her out from the shadow of such an overwhelmingly dominant president and husband?

What resources were most interesting and helpful? Without a doubt, Lady Bird Johnson’s 123 hours of audio recordings she kept to document her experience in the White House- beginning November 22, 1963 through January 31, 1969. These tapes helped me solve the puzzle because they revealed just how substantially involved Lady Bird was in the LBJ presidency— the transition into it, the exit out of it, and the push on Civl Rights, Great Society, environmentalism, and of course Vietnam. They reveal a brilliant political strategist at the center of the White House, yet they were almost totally overlooked.

What surprised you the most?

The extent of Lady Bird’s power and influence with LBJ and in shaping the arc of the Johnson presidency.

What are you glad you found out?

Discovering Bird’s ambitious environmental agenda concealed by the term “beautification,” especially in relation to bringing access to nature to the most underserved communities of color in American cities, is one of the most exciting, an untold stories I was able to uncover.

Has your impression of the 1960s changed after writing this book? My visceral sense of the 1960s had been rooted in images of hippie counter-culture, the anti-war movement, civil rights and Black Power. And the rise of the women’s movement. Writing this book helped me see how much of the 1950’s carried into the 1960s, in terms of much of the country’s conservative attitudes toward rapid social change, especially in the South, but really everywhere. The Civil Rights legislation passed by the Johnson administration was understood at the time to be the end of the story- the magic wand to wave away the nation’s racial subjugation. But passing laws, it turns out, was only the start, and much of the backlash in the South and among “law-and-order” advocates all over the country showed just how much the rigidities we associate with the 50s carried over into the ’60s, and well beyond.

What’s one thing you hope you’ve accomplished with this book?

I hope the book will re-cast the historiography of the Johnson presidency by placing Lady Bird Johnson where she belongs, at the center of the story.

Fiona Davis, author of The Chelsea Girls

When I chose the Chelsea Hotel as the location for my fourth book, The Chelsea Girls, I knew it had been home to generations of bohemian artistic types over its 140-year history, but I didn’t realize what a vortex of creative energy it was during the Sixties. The more I researched, the more I became determined to give that particular decade more than a passing mention.

The building’s early incarnation as an 1880s utopian cooperative – where musicians and plumbers, electricians and artists, might live side by side – quickly failed, and after going bankrupt in 1905 it was reinvented as a hotel. At the Chelsea, guests might come to stay for a few nights and end up in residence for decades, and early cultural icons who gravitated to the hotel included Dylan Thomas, Mary McCarthy, and Jack Kerouac.

The Sixties brought a new, decadent energy to the building. Playwright Arthur Miller, who lived in room 614, wrote that the building vibrated with “a scary and optimistic chaos which predicted the hip future, and at the same time the feel of a massive, old-fashioned, sheltering family.” Rooms went for ten dollars a week, and aspiring young musicians, actors, painters, photographers, authors, and composers checked in searching for both inspiration and entertainment. And they found it: Leonard Cohen met Janis Joplin in the elevator one day, resulting in a mad love affair and his song “Chelsea Hotel No. 2.”; Andy Warhol swarmed the hotel shooting his seminal movie Chelsea Girls there; the Grateful Dead even performed an impromptu concert on the roof one hot summer night.

The Chelsea Hotel stands as a reminder that even as New York City cycles through ups and downs, economic riches and ruins, it is the artists who keep the city vibrant. No doubt some of the ghosts of the long-gone residents of the Chelsea Hotel still wander the hallways, wondering what role the building will play in the years to come.