Author Q&A

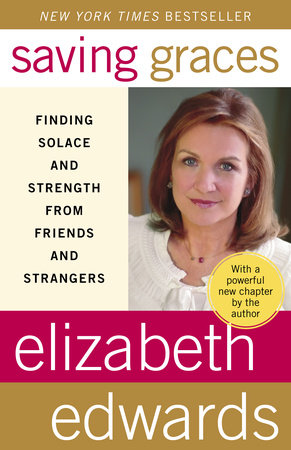

How are you feeling these days–in terms of your spirits and your health?At my last clinic visit — after a round of scans to check for signs of cancer — my doctor, Lisa Carey, looked at the stack of papers I brought with me to work on while I was waiting and she said, “You have a lot going on, but cancer is not one of them.” Those were great words to hear, and it is impossible not to feel buoyed by that news. Are there still lingering ailments? Sure, but “cancer is not one of them” so I am not complaining. When did you begin to write Saving Graces? What were the challenges of trying to capture your life in a manuscript? The bulk of Saving Graces was written in the winter and early spring of 2006. I had written pieces before but the book started to take shape only after I made a daily commitment. For the months it took to write, the children always knew where to find me: at the computer. Sometimes, I have to admit, I was also in the attic, going through old photographs or newspaper clippings to make certain I had names and dates right, and — far from being work — that part was great fun. The challenges of capturing any life in a book are that it took 57 years to get here and no one will read something that takes 57 years to finish. So the process of editing means by definition leaving things out. It is hard when you have lived the life to know which parts can be conveyed in a book and which parts should be relegated to family reunions. That is where having a great editor, as I did with Stacy Creamer at Broadway Books, is invaluable. Your childhood recollections are full of interesting details. How did living overseas shape your sense of what it means to be an American? Do you think being an American today conveys the same meaning as when you were a child? Growing up overseas in military communities meant that we were totally American without having many of the touchstones to American culture that others in our generation would have. (Imagine that there is a decade in your growing up where you didn’t see a single television show, for example.) I think in many ways it meant we clung to being American even more fiercely. I have tried to pass that aspect to our children, developing a deep and real pride in our country. There was a time before September 11th when I think we might have seen a general drift away from a conscious patriotism generally, maybe because we didn’t have a single threatening superpower like the Soviet Union on the horizon. But after September 11th and since then, there has been a renewal in the open expression of patriotism and in the values that we hope are associated with this country. In what ways were the childhoods of your four children different from your own? What were the earliest lessons you tried to teach them? The one thing I wanted to give my children was a single place that they could call home, something I never had. It didn’t work out completely, but in some ways they have had the best of what I experienced and what I am dreamed of having. They have traveled, as I did, but they have real roots in a place, too. The earliest lessons have to be the simplest: honesty, responsibility, respect for others. In truth, I think you have a lot of responsibilities as a parent. You need to teach your children cleanliness and manners and a work ethic and real ethics. You need to teach them how to make dinner for themselves and how to study for a test and a thousand other things, big and small. But none of this matters if you don’t also give them wings. You never know how well you did at parenting until they leave. As hard as it is to see them go, the job is not complete until they are able to fly for themselves. So I have spent a lot of time urging all four of my children to try new things, to meet new people, to step up on their own. Having been raised in a military family, you came to know about this particular kind of community and the untold ways its members support one another. What should civilians (whether they are political leaders or not) do to “return the favor” for the tremendous sacrifices made by soldiers and their families? There are lots of ways in which we could show our appreciation to military men and women and their families, starting with the incredibly simple act of saying “thank you” when you cross their paths. I am always heartened when I see signs in stores that give discounts to people with military ID cards — which happens a lot in North Carolina where we are blessed with lots of bases. If you live near a base where there are a lot of deployments, you could reach out to the family support centers on those bases and see if there are ways to help. I admit that I have been disappointed for some time by our governmental stinginess with the military, the military family, the veteran, and the veteran’s family. It would be great if all the civilians spoke up — it is hard for active duty military men and women to do so — for pay increases (so that some military families don’t qualify for food stamps), for better medical care even if the military family is not near a base and better care for all veterans, for more retirement support for widows and widowers. These issues come up in Congress all the time, but until they understand that all their constituents, not just those in the military, care, Congress will not give these issues the priority they deserve. Was it difficult for you to make the transition from your legal career to motherhood? What advice do you have for working women who are about to become mothers? Once I went to an ethics seminar. All North Carolina lawyers, probably lawyers everywhere, have to take a certain number of continuing legal education course in ethics. (I admit I always assumed that unethical lawyers, like unethical professions everywhere, knew what was ethical and what was not, but chose to act unethically. So I wasn’t sure what the purpose was, but I went anyway.) At this seminar, a young woman lawyer contemplating having children asked me about balancing, and I told her what I did: I decided which job, mothering or lawyering, was the priority — mothering won — and from that point on balancing was easy. When I was doing it day to day, which I did at first, it was very difficult; I could make the argument for why this school recital was important and why this contract was important. I made decisions that allowed me to work: my children attended the YMCA after-school program, for example, but when there was a teacher workday or some other conflict with work, mothering won out. You described how hard it was for you to write the passages about Wade’s death. How did you get through this part of your book project? What did you most want your readers to know about him? Writing about Wade, like thinking about him, is both hard and wonderful. It was hard to revisit the things I wrote at the time he died because I was so raw then and the writings reflect that. As for what I wanted the reader to know about Wade, I knew first that they would not trust what a mother had to say, but I was lucky. Alise Tharpe had gone to school with Wade, and she described him in a letter she gave me which she allowed me to include in the book. Her description of a sweet, fun, and monumentally thoughtful boy will, I hope, convince the reader about Wade in a way my words never could. Where do you think Cate’s law degree will take her? Has she shown any interest in having a political career?Cate is interested in public interest law, that is working with governments, non-governmental organizations or non-profit organizations on issues of public interest, such as access to justice, access to democratic processes, constitutional, civil and human rights, energy and environmental policies, labor policies, global political, financial, trade, and technological issues, poverty, or children’s or women’s issues. Although I thought she was terrific on the campaign trail, usually appearing by herself and taking questions, she has not expressed any interest in a political career. In the book, you write candidly about differences of opinion between your husband and John Kerry over certain aspects of the campaign (including when to concede). Was it difficult to decide how frank to be in your memoir? Were there certain topics you decided would be off-limits altogether? I tried to tell the story in the way that would be truthful. It would have been impossible, for example, to tell the story of the end of the campaign and the beginning of our fight against breast cancer without saying how hard it was to let go of the campaign, that John did not want to let go until the promise to count every vote had been fulfilled. Politics are like other human interactions; people will have differences. I didn’t describe every difference of opinion not because it was “off-limits” or to keep a secret but because not every difference of opinion is structurally a part of the book. Do you think the political landscape has shifted since the 2004 election? The public trust on which the President counted in 2004 has clearly eroded as more and more information about the initiation of the war in Iraq are revealed, and frankly, I don’t know how you rebuild lost trust. It is one of the reasons why it is important to be honest whatever the short-term cost. And the lobbying and leak scandals in Washington have driven a further wedge in the public trust in any part of their government. But I think that the American people want to believe in their President and want to believe that their elected officials care about them; that hasn’t changed. How has your understanding of cancer diagnosis and treatment changed now that you have been through it? Did you have any of the classic risk factors (such as a family history of the disease)? No one on my mother’s side of the family has had breast cancer, so I don’t think I have a relevant family history. What we are learning now — and my doctor, Lisa Carey, is responsible in part for these breakthroughs — is that breast cancer is not one disease but an umbrella for lots of cancers that occur in the breast, with different causes and different prognoses and, we have reason to hope, different cures that can be identified as we identify the causes and triggers for each cancer. As to the current treatment, I am now much more informed about how physically difficult the chemotherapy regimen is and how it alters every part of a patient’s life, whether or not they have a support system in place. How did you react to becoming a patient rather than a caregiver? I fought looking at myself as a patient because I didn’t want to be a “victim” of cancer. I wanted to get started immediately after the biopsy results; I wanted to turn the tables on cancer and be the aggressor. But in the end, I was the patient; I was, undoubtedly, the victim, eventually physically leveled by the treatment. I was very lucky though, because I had a caregiver; my husband John took great care of me. Did your illness affect your feelings about America’s health care system?My experience confirmed what I believed I knew about the health care system — that we have an inequitable system that provides great health care for a few and less thorough health care for everyone else. People come from all over the world to get medical treatment in America because we have such fine hospitals and doctors. Too many Americans, however, don’t have access to them. Maybe they don’t have health insurance or their health insurance doesn’t cover the treatment that would be the very best for them. Whatever the excuses, my experience convinced me we need to finally do something to rectify the inequities. You have received much from friends and strangers, and you have also given them much; the computer lab established in Wade’s memory is but one example. How would you advise readers who want to do similar good works that might bring solace and strength to others? Where have you seen the most need in your travels throughout the country?In the book I tell the story of Helen who bought crayons for her Sunday School with the little money she was able to use for her “good works” and I also tell the story of Lyght who delivered meals to the needy. In giving, the size of the gesture is a poor measure. What matters is that you actually do it. We too often talk about giving Christmas to a needy family or working a few hours at the Goodwill Store, but then we don’t follow through. For those who are grieving the loss of a loved one, sometimes it is helpful to do something for others that you can see, and if that feels right to you, consider going to your local parks department and asking to see their wish list. It might be bulbs for a garden or a tree on a greenway or something more expensive, but you will be able to find something. For those who don’t need the affirmation a physical gift provides, there are lots of opportunities to make a difference in people’s lives, but the key here is continuity. Your church, your social services office, your school system, your hospital, local non-profit organizations can all provide you with their versions of wish lists — taking meals, reading to the young or the old, visiting with the home bound or hospitalized, filling the shelves of the food bank. But the real key is to commit to help regularly, to be someone that they can count on. You’re a lifelong lover of literature and have tried to nurture this trait in your children also. What books would you like to recommend to your readers and their children? Everyone has their own taste in literature but I think it is a good idea to include in your regular reading two categories of books. One, read a classic at least once a year. You know, a book you were supposed to read in eleventh grade but never really did. Read it now. You don’t have to give up whatever you love to read; just include something that stretches your mind a little. And two, read something by authors from your state or region. You might find a little of yourself on those pages.Saving Graces concludes with images of your new home and other new beginnings. What are your dreams for the next chapter of your life?There will be mornings, not long from now, when I will wake up and look across the meadow in our backyard at deer grazing — I hope they won’t be in my garden. And I may make breakfast again, like I did a decade ago, for a houseful of boys and girls who stayed the night with Emma Claire and Jack. And I will finally have a place to paint and write, and a warm family kitchen in which to cook. I hope to have a small tractor — maybe this Christmas (a hint to John) — so that I can work on the paths in the woods I hope to clear so that when we grow old we can walk the woods in the early mornings. Maybe Cate will call from her new life and maybe John will bring me something he read, like he always does, and if they do, I will certainly think life is nearly perfect. Nearly is a word I have to use after losing Wade, but nearly perfect is not so bad a dream.