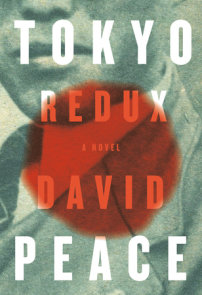

Author Q&A

A conversation with DAVID PEACE, author of TOKYO YEAR ZEROQ: You have written several books, and Tokyo Year Zero is the first to be published in the United States. For the benefit of American readers who are unfamiliar with your work, tell us a little bit about yourself. How long have you lived in Japan and how did you come to move there? Is writing your main occupation?A: In short, I’ve lived in Tokyo since 1994. Initially I came here to teach English (as a foreign language).However, I’ve been able to write “full-time” since 2001.In a nutshell, here are the details:• David Peace was born in Ossett, West Yorkshire in 1967• From 1983 to 1988, he was in a punk band, unsuccessfully• He graduated from Manchester Polytechnic in 1991• From 1988 to 1992, he wrote one novel, two plays, three screenplays, and a lot of poetry, unsuccessfully• He lived in Istanbul from 1992 to 1994• He moved to Tokyo, where he initially taught English, in 1994• He married in 1996• His son was born in 1997• Nineteen Seventy-four was published in 1999 by Serpents Tail• Nineteen Seventy-sevenwas published in 2000• His daughter was born in 2000• Nineteen Eightywas published in 2001• He was awarded the French Prix de Roman Noir 2002 for the French edition of Nineteen Seventy- four• Nineteen Eighty-threewas published in 2002• He was chosen as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists 2003• GB84 was published in 2004 by Faber and Faber and awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction• The Damned Utd was published in 2006• He was awarded the Deutscher Krimi Preis (the German Crime Novel Prize for 2006) and the Krimi Welt Besten Liste 2006 (The Critics Crime Author of the Year Award) for the German edition of Nineteen Seventy-four• Tokyo Year Zero will be published in 2007, followed by Tokyo Occupied City in 2008, and Tokyo Regained in 2009• His books have also been translated into Italian, Japanese, and Russian• He continues to live in Tokyo, but rarely leaves the room in which he writes, reads and listens to music• Drinks, smokes and occasionally sleepsAnd that really is all there is to sayQ: Tokyo Year Zero is based on real events: It is about a series of horrific rapes and murders that took place in 1946 in Tokyo and the hunt for their perpetrator. How much of what takes place in the book actually happened? Is the central character, Detective Minami, based on a real detective who worked the case?A: The book follows the actual course of the investigation as it happened and the dates match the real dates. So the organization of the police and the structure of the investigation are accurate, as are scenes such as the interrogation of Kodaira, the killer. And so there would have been a detective of Minami’s position and rank in the investigation BUT my Minami is a fictional character.Q: Did you do very much, or any, research on these cases in order to write the book?A: Every one of the seven books I’ve written has been based on actual events and all of them required exhaustive and extensive research (which I enjoy). Tokyo Year Zero was by far the biggest challenge as, for the first time, I was writing about times and places I had not lived through and a country which was not my own. But I was very lucky to be greatly assisted in my research by my Japanese editor, Nagashima Shunichiro. So the research took about six solid months, then six solid months of writing (day and night).Q: The book takes place in Tokyo one year after WWII has ended. The title "Tokyo Year Zero" conveys a sense of things having been completely wiped out, of there being nothing left, but also a sense of beginning again, of the slate having been wiped clean. How did you come up with the title and what does it mean to you? Do you feel it’s partly hopeful?A: The title was actually inspired by Rossellini’s film “Germany Year Zero,” set among the ruins of Occupied Berlin. My next book, the second book in a trilogy, continues the homage—Tokyo Occupied City being inspired by Rossellini’s “Roma Open City.”To me, Year Zero means exactly that; no history, no future. And so, no—I don’t see it is partly hopeful (though I realize I am possibly the most pessimistic person you’ll ever have the misfortune to meet).Q: In this version of Tokyo in 1946, it feels as if a war is still going on. Air raid sirens are going off, buildings are burning, people are dying. It feels eerie, and grimy; there are lots of alleys and dark corners. Was this what the city was really like then? Did a wish to convey the harsh reality of a war-torn region play a part in your writing this book?A: Obviously, I can’t say for sure that this was what the city was like in 1946. However, as I said above, I did do extensive research and that did include talking to people who had lived in the city at that time. But this book is very much from the perspective of the Defeated and the Occupied, rather than the Victor and the Occupier. So when you talk to Japanese and Americans who were in Tokyo in 1946 there is obviously a tremendous contrast in how they saw the city at that time. But the city was largely ruined and I wanted to convey that impression as strongly as I could. Also the feeling that the war was not really over (and even now, one could argue it still isn’t), the feeling that history and the past never really go away. For example, the part of Tokyo in which I live—the East End—was bombed completely flat in one single night in March 1945, with well over 100,000 civilian deaths (as recounted within the book). And every time I set foot outside my door, I am conscious that I am walking on the dead, that on some (psychic?) level, in some way, that horrific, terrible night is still happening, over and over, beneath my feet, these stones. And I have to say that while writing the book, every time I took a break and switched on CNN I was witnessing another war, another defeat, another occupation.It really does never go away, never end.Q: The reader follows Detective Minami as he traces and re-traces ground in the city, trying to find new bits of evidence—and also trying to hold on to his sanity. Fragments of his thoughts and remembered conversations form a kind of parallel narration in the book, a relentless inner voice that gets louder and more frequent as time goes on. How did you decide to structure the book this way, and what are you trying to convey with your use of these long italicized passages?A: Well the city, the country, was literally broken and smashed into fragments at that time and so I wanted to convey that sense of fragmentation, destruction, on a personal level. Also, it is actually how I personally feel/think; we all have our memories, our dreams, our fears inside us and we (or at least I) have great difficulty controlling them. So, war or no war, reality (whatever that might be) is surely very, very fragmented and subjective—we are all fractured contradictions (and it’s no crime, no sin).Q: Of all the refrains, one of the most haunting is “No-one is who they say they are.” Minami feels this applies to everyone around him. As the story goes on, we realize that the statement may apply to him, as well. What purpose did you wish that statement to play, for Minami and for the reader?A: Literally, at that time, many people had hidden their identities and their pasts and taken new names, new ranks, new jobs etc in order to escape the purges and the prosecutions. And obviously the same was true in France, Italy and Germany. So many, many people really were not who they said they were, including Minami. However, and without getting too “deep” again, are any of us really who we say we are? I don’t think so; I think we are much more complicated and divided than we appear or try to appear to be.Q: In this fictional world, traditional values—the formality, precision, and politeness of Japanese culture—are being enacted in a place that has been completely torn up and changed by war. It’s a clash that is hard to overlook in this narrative. What, if anything, were you trying to say about those traditions and their clash with a modern war that paid them no heed? Was it hard to find the right way to say it?A: I was simply trying to reflect what I thought Japan was like at that time; the legacy of the past/tradition, the pain of defeat, the confusion of occupation and how these all collided both in individuals and in society. And yes, it was difficult; many non-Japanese have clichés and stereotypes about Japan and the Japanese—as do some Japanese people themselves—and such people will always tell you, “A Japanese person would never do this or say that etc”—as if they have met every one of the 120 million people who live here—and obviously such generalizations are utter nonsense BUT, that said, you have to be aware of them and make sure you don’t add to them!Q: Have any of your previous books been published in Japan, in Japanese? What has the reaction been? What do you think the reaction will be when Tokyo Year Zero is published there?A: My first four books—the Red Riding Quartet— were all published here and the first one, Nineteen Seventy-Four, was a “bestseller,” even. Year Zero will be published in October here by Bungei Shunju. As I say, Bungei have greatly assisted in the research of the book and they seem very, very enthusiastic. It’ll be in hardback with a big promotion. So let’s hope their enthusiasm and excitement is justified in the reaction from press and public.Q: You have in the works two more books that will be linked to Tokyo Year Zero. Tell us about them. What is each about, and will we see any of the same characters again?A:As with Year Zero, both books are based on actual crimes that happened during the Occupation: Tokyo Occupied City,which I’m writing now, is based on the well-known “Teigin Incident”; in January 1948, a man posing as a public health official entered a bank in Tokyo and administered an anti-dysentery medicine to the staff. Within minutes, ten of the staff were dead and the manwas gone. Hirasawa Sadamichi was arrested, convicted and sentenced to die for the crimes. However, his execution was never carried out due to worries about the surety of his conviction. He died in 1987 having spent 40 years on death row. To this day, many Japanese remain deeply divided on Hirasawa’s guilt or innocence. Tokyo Regained is based on the “Shimoyama Incident”; in July 1949, the body of the President of the Japanese National Railroad was found dead beside the tracks in North Tokyo. The case remains unsolved to this day. And yes, they will feature some of the same characters; Nishi from Tokyo Year Zero, for example, narrates the second book. But I would hope they can also be read as “stand-alone” novels. That is the ambition, the challenge, at least. And all three books are about DEFEAT and even though most of us in the US and the UK, of my age anyway, have been fortunate enough not to live through a war (in our own country) or an occupation, we have all experienced defeat—we are all, to varying degrees, defeated.