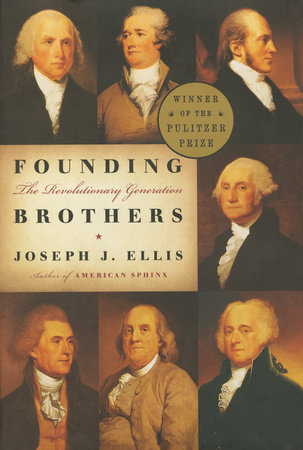

Author Q&A

A Conversation with

Joseph Ellis

author of

FOUNDING BROTHERS

Q: What made you decide to follow your award winning biography of Thomas Jefferson with Founding Brothers and what kind of research went into this book?

A: After I finished my last two books, on John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, I realized that I had read much of the correspondence produced by the founding generation. I did have to go through the Washington letters, and read the Burr correspondence, but otherwise I had pretty much started a new book on the entire group of founders without quite knowing what I was doing. And throughout those letters, they kept referring to each other as a "band of brothers." We think of them as Founding Fathers, but they saw themselves as a fraternity. I should add that my title fails to include the one sister in the group, Abigail Adams, whom I think was an equal partner in her husband’s political career.

Q: You open the book with the sentence, "No event in American history which was so improbable at the time has seemed so inevitable in retrospect as the American Revolution." How so?

A: We regard the success of the American Revolution as inevitable because we have lived so long as a nation, over two hundred years, with the consequences of its success. Looking back over that stretch of time, we can only see the unfolding of American destiny. But for those involved in making that destiny happen, everything was contingent, problematic, unclear. After all, before 1776 there had never been a successful war for independence by a colony of a European power, had never been a nation organized around republican principles, to include the principle of popular sovereignty. So all the great achievements of the revolutionary generation were, in fact, unprecedented.

Q: Of the men you write about in Founding Brothers, who do you think was the most "revolutionary" and who do you think has left the greatest legacy?

A: They were all revolutionaries, at least in the sense mentioned above, that is they were trying to do something that had never been done before in modern history, and they were bold enough to take on the dominant military and economic power in the world, Great Britain, fully realizing that if they lost the contest they would all have been tried and hanged as traitors. Washington was probably the most indispensable character in the group. Without him, the effort would have most likely failed. Jefferson’s legacy is most lustrous, because of those magic words he wrote in the Declaration of Independence. Franklin was, in my judgment, the wisest. Hamilton was the most brilliant, the one who would have scored the highest on the SAT’s. Madison was the sharpest political thinker, though I think Adams ranks right up there with him. In fact, Adams is probably the most under-appreciated of them all and the founder whose letters most fully reveal the hopes and fears and ambitions they all shared. But selecting one founder over another misses the main point, which is that they succeeded because they were a collective.

Q: Why did you choose to tell the story of this generation using specific events (i.e. the duel between Hamilton and Burr; the private dinner for Hamilton and Madison at Thomas Jefferson’s home; the Farewell Address of Washington) as starting off points?

A: If there is a method to my madness in the book, it is rooted in the belief that readers prefer to get their history through stories. Each chapter is a self-contained story about a propitious moment when big things got decided (i.e., the location of the nation’s capital; the decision to take slavery off the national agenda). In a sense, I have formed this founding generation into a kind of repertoire company, then put them into dramatic scenes which, taken together, allow us to witness that historic production called the founding of the United States.

Q: How was it that these men, with often bitterly different beliefs and viewpoints, were able to collaborate in a way that seems almost unimaginable in today’s political arena?

A: Alfred North Whitehead once said that there were only two occasions in world history when the political leaders of an emerging nation behaved about as well as we could possibly expect: Rome under Augustus and the United States under the American founders. I think there are two reasons why this group managed it so effectively: First, they all knew each other personally, meaning they broke bread together, sat in countless meetings together, were forced to interact in intimate, face-to-face settings; second, they shared the common experience as revolutionaries who had been "present at the creation," a bonding process that generated mutual trust and a common sense of purpose. They knew they were making history. And unlike other revolutionary elites in places like France, Russia and China, they did not, with one exception, allow their rivalries to take a violent form. Instead of killing one another off, they argued endlessly. This is one of the most misunderstood features of the entire generation; namely, the very human competition among them. We have made them into statues but statues cannot throb with ambition or shout obscenities at each other. Here was a case where the best, not the worst, were full of passionate intensity.

Q: How do you think Jefferson, Hamilton, Franklin, Adams, Burr, Washington, and Madison would regard politics and politicians today and are there any modern day political figures who closely resemble any of the Founding Brothers?

A: Very few, if any, of the founding generation would be willing to run for political office today, since the democratic political process we have created during the ensuing two centuries would strike them as demeaning. The present primary system, the incessant scrutiny of the media, the fund-raising obligations generated by all national campaigns, the relentless pressure created by pollsters to shape policies in accord with popular opinion–all these staples of democratic politics in contemporary America would alienate the founding generation from public life today. They were a pre-democratic generation, meaning that they regarded themselves as a political elite whose highest obligation was the public interest, which is often quite different from the popular interest at any given moment. The one current political figure who resembles the vanguard members of the revolutionary era is John McCain, whose position on campaign finance reform is so obviously driven by a genuine commitment to the public interest, and yet whose failure also exposes the suicidal fate awaiting anyone so disposed in our current political culture.

Q: In the presidential election of 1800, Americans chose between Jefferson and Adams. As you write, "Choosing between them seemed like choosing between the head and the heart of the American Revolution." In 2000 it’s Bush v. Gore and it is hard to imagine anyone saying the same about this choice. What has happened?

A: Comparisons between then and now, say between the election of 1800 and the current presidential contest between Gore and Bush, are always treacherous. On one level they call to mind Henry Adams’s famous observation: if you look at the history of the American presidency, you would conclude that Darwin got it exactly backward. At another level, the comparison is unfair to Gore and Bush, because we are measuring them, not against the real Adams or Jefferson, but against our mythological versions of them. That said, I do think the current generation of political leaders cannot possibly measure up to the founding generation. It’s not that there was something special in the water back then. Or that God, or the gods, gave this group some special grace. It was that the crisis we call the American Revolution generated the conditions essential to call forth heroic acts of leadership. The only analogous crisis in American history was the Civil War, and that did give us Lincoln. Perhaps the Great Depression also qualifies. And there we got Franklin Roosevelt. Perhaps we ought to conclude that our democratic culture really does not want strong leaders except in national emergencies. Leaders can be dangerous, can do bold things. In an ironic sense the founders created a system that is designed to function without strong leaders, to be a machine that runs itself. And in an equally ironic sense, the current crop of lackluster leaders is symptomatic of the abiding health and prosperity of the United States as we enter the new millennium.

Q: There seems to be a renewed interest in the revolutionary generation these days. The Patriot is shaping up to be one of the summer’s biggest movies, the History Channel has a series planned on the Founding Fathers, HBO is making a film about the infamous Burr Hamilton Duel. What accounts for all this attention at this particular moment?

A: It’s true that, until the recent success of The Patriot, there have been very few Hollywood films about the American Revolution that have enjoyed critical or commercial acclaim. The only one I can think of is Drums Along the Mohawk by John Ford in the late 1930s. I think part of the reason for the failure is that the eighteenth century is pre-photograph. All the visual renderings we have of that era are stylized portraits. We have no mental pictures that make the revolutionary generation fully human in ways that link up with our own time. Another reason, I think, is that these great patriarchs have become Founding Fathers, and it is psychologically quite difficult for children to reach a realistic understanding of their parents, who always loom larger than life as icons we either love or hate. I see a certain connection between the surge of interest in the World War II generation, what Tom Brokaw has called "the greatest generation," and the current surge of interest in the revolutionary generation, which I happen to think wins the election for "the greatest" hands down. In both instances we are beginning to come to terms in a deeper and more detached fashion with the role of our ancestors in making our modern America what it is. If Founding Brothers turns out to be part of that process of mature appreciation, I would be quite pleased. I would love some reviewer to say that if you liked Saving Private Ryan, you will love Founding Brothers.