Interviews

Mary Oliver Talks Hard Work, Discipline, and Poem Memorization

An Interview with the acclaimed poet

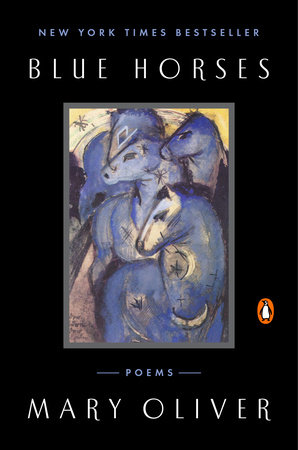

Amy Brinker talks with Mary Oliver about her collection, Blue Horses.

AB: To begin, I was hoping you could read Blue Horses, the poem.

MS: I will do it with pleasure. This is um, a paper I know nothing about until somebody in the ‘60s sent me a little book. It was in German text so I couldn’t read it, but oh my, the paintings were extraordinary and so it stayed with me. Oh, I think that was in the ‘60s, it stayed with me a long time and this is the poem I finally wrote about it. And it’s called, it’s complete title Franz Marc – Blue Horses.

I step into the painting of the four blue horses.

I am not even surprised that I can do this.

One of the horses walks toward me.

His blue nose noses me lightly. I put my arm

over his blue mane, not holding on, just

commingling.

He allows me my pleasure.

Franz Marc died a young man, shrapnel in his brain.

I would rather die than explain to the blue horses

what war is.

They would either faint in horror, or simply

find it impossible to believe.

I do not know how to thank you, Franz Marc.

Maybe our world will grow kinder eventually.

Maybe the desire to make something beautiful

is the piece of God that is inside each of us.

Now all four horses have come closer,

are bending their faces toward me

as if they have secrets to tell.

I don’t expect them to speak, and they don’t.

If being so beautiful isn’t enough, what

could they possibly say?

AB: Would you please speak a little bit about your poetry handbook, which you wrote in the ‘90s I believe?

MS: I think so. It was many years ago. I don’t, I’m bad on time. I get, it gets worse and worse as I get older. It’s how I did, I think with the, what’s interesting. I was invited to come to Sweet Briar College on a Writer/media writer’s residence, but I had once class with about 13 students in it, which I met, was supposed to be for two days per week, but I met them for three days a week. I hardly got to know their names. And I realized that I have never in my life, myself been in a writer’s workshop. So I had no perceived notion of what was done there. Nothing. And I had some weeks, perhaps a month to think about this. So I started writing down what helped me. What would’ve helped me and that is entirely what is in the book. And it takes up subjects, that I think, that I have since been visited through to many uh, workshops. And the method, maybe didn’t – – along, but the method of everybody reading somebody’s poem and then comment on it and then going on to the next one. I didn’t feel was sufficient.

And, and I also feel very strongly that in the other art disciplines the apprenticeship is expected. You learn about immaterial, you learn about different colors, you copy things, you imitate, you, as – – said you teach your hands to do it. And with poetry to teach your mind to know things. Like the sound of words, some are very soft, and then the mutes for example, are very hard words. And I would always start by saying what’s the difference between a rock and a stone, it’s the sound. So I went a great deal into sound.

I also have found out that in my own life, by that time, being poor, once in a while I had to take a job. I always took an uninteresting job so I wouldn’t get interested in it. But I learned to wake up at 5:00 and usually you go to work at 9:00. So I had a couple hours to write. And I discovered that if I was at my desk at the same time, I would say I’ll be there at 5:00, some part of this creative process was there too. I know the students talk about, you know, they’re busy, they have papers, they have readings, they have things to do and then they want to work on poetry so they, they turn on the lamps and they sharpen their pencils and they get the cup of tea, and the they turn on the radio and they wait to turn into poets. But if they were expected and your mind does think of creative things all day long, you’ve made a collection that part of you knows you are going to be there, you are there and this helps so many students. Just wonderfully.

And the other thing that I warned, were many, many things in the book, which yes, people have found helpful. You must remember that other group of poets, young writers, is a social group and nobody wants to hurt anybody else’s feelings, to badly, anyway. And also, it might not be the kind of thing you do anyway. And young writers are rough in the beginning and other students try to be helpful will often say well that doesn’t work. And I would say, well I see what you want to do, except it’s too rough, it’s not working well yet, but stick with it. That’s your voice wants to work something out in that way. Stick with it and we’ll watch and see what you can do. Don’t, don’t just try to change.

And the other thing that happened, is what’s voice, what’s style. And this is very important. Somebody writes a poem and uh, people say that’s pretty good, that’s pretty nice. Oh, I like this line a lot it works. So try more, do it here. And after the fifth poem the person is in a kind of rut of doing it a certain way. And it’s you get much more if you talk about words, you talk about rhyme, or you talk about rhythm, you talk about line breaks. All of these mechanical things that uh, that people use. You talk about the IM and what that feels like. And – – and what that feels like. Half of these kids don’t even know those words anymore. That was the bulk of what I did. Just everything that I dug out for myself and I couldn’t find in any book.

AB: I think that that’s true that you want to find your own voice, but you don’t want to get stuck and that’s something.

MS: You don’t want to get stuck. But you shouldn’t be afraid of imitation either.

AB: Oh, interesting.

MS: Again, young artists go to museums, copy painting and they learn. And a lot of this learning just sinks in you and then when you have something to say, you have the way to say it.

AB: Um, that’s so valuable to uh, to force of work ethic, as well.

MS: Yeah.

AB: Especially for something that is purely artistic.

MS: – – and it worked. The other thing I did, which was kindness and I wanted to do this, I would not let the book be in hardback.

AB: Why is that?

MS: It’s only paperback. Kids have to spend so much money on books, I’ve seen them walking around with $35 heavy books on how to write poetry and I didn’t want to do that. And that’s one reason because I’m sure because it’s available. And so that’s my story of uh, and when I first started to teach, I had all these things laid out and put them in a Xerox format and I did this for about three years and learned from the students what was helpful. Wrote and rewrote and added things – – and so forth and there it was. I wrote a poetry handbook.

AB: I have a friend who graduated from her masters a couple years ago and she says it’s still being taught and it’s kind of the bible for learning how to write poetry. So that must be a wonderful legacy.

MS: Yeah, that’s wonderful. I’m very glad of that. I mean all the things that worked for me and uh, I just knew it from writing every day. I was just fascinated by the sounds and uh, I, I used – – something I would on a chilly evening. My first example of the different sounds. You know the first heavy sound in, in that poem is about five or six sounds. Uh, it’s a sound of a heart, my heart’s – – stink, you give his heart a – – shake and that shake wakes up the whole calling kind of sound. And I use that method always. I think it works. I think it helps.

AB: Well in this new collection of Blue Horses, you mention a few, a few famous poets. You have a poem called “Remee” and you have, you mentioned “Whitman” and I was wondering many people might come to poetry through you and start reading poetry and I was wondering if you could give a couple collections or couple authors or a couple poets who you think are must reads for people new to poetry.

MS: Yeah, that, that’s a difficult question because the taste is so wide.

AB: Of course.

MS: But I, so I can only speak for myself. Uh, Whitman is the master in our language. Coleman Barks’ translations of Rumi uh, are the master in whichever he originates Rumi – -, Coleman is the master. I read, I read a Rumi poem every morning.

AB: Do you?

MS: I absolutely do. It’s very, he’s incredible.

AB: A different poem every day?

MS: I, yup. Coleman has a book out that is uh, one, year with the Rumi. I have all his books. This is one where you can just pick it up in the morning and get a poem. – – it’s not the first year – – .

AB: Right. Guess you repeat maybe.

MS: Yeah, well he’s been working on this for thirty years. And he’s got a new book coming out this fall I believe.

AB: Oh, that’s a great recommendation. I’ve going to start reading a Rumi poem in the morning. That sounds pretty good.

MS: It is. It’s really nice. If it’s a bad day or it’s been a bad day it sets you up. Or thinking about other things.

AB: Yeah.

MS: No, he’s wonderful. He’s good company, but he don’t ask for the – – . I feel this way there are so many good poets, master poets, younger poets that have wonderful stuff that I leave that to the kids, but I try to begin to do it this way. I’ll say I want you to memorize poem. And they go, they groan. Given the poem they don’t want to memorize. I say you pick the poem that you want, just read around, see what you find, find some poem you really like to know when you’re lost some day on the mountaintop and they, that they find agreeable and do it themselves. And I say every morning read this poem for 30 mornings and you will know it. So that’s the way they memorize. And that’s the way they notice things within the poem. I know one of the favorite ones was the Lords is the Snake, which has a lovely amazing sound. And uh, that’s what I do – – poets, of course. There’s, if I got a list and people say who’s been important to you, um, you know I could say 50 people.

AB: Oh sure. That’s an unfair question.

MS: – – mad because I forgot two others.

AB: Well sure. I know. People always want to know though, it’s always interesting to hear what people read.

MS. Yeah, well I very, was very much connected to reading a lot of the current poems. At some point in my career, and James Robert Bride – – Gulloway Canal, that group that was very, very important to me. And they were the ones who really took up – – . More American language. Everybody – – is fantastic. So many different styles.

AB: And you think its valuable to read different types of poetry, I’m guessing. Different kinds of–

MS: [interposing] absolutely. Absolutely. And those – – .

AB: Why’s that.

MS: Because um, I, they teach literature chronologically.

AB: Yeah.

MS: It’s hard to read that – – stuff.

AB: Yeah.

MS: Because we don’t do it anymore.

AB: Yeah, that’s true.

MS: And you can’t enjoy the line unless you’re really familiar with it. Even if he, you miss that part. And uh, it kind of the music of the poem, which is, which is what delivers the message.

AB: That’s kind of nice to hear. I mean it’s kind of nice to hear that you don’t have to appreciate that right off the bat. You can kind of warm up.

MS: I think what good at.

AB: Yeah.

MS: To these poets that know the history of many of those poets – -, you need to know the history.

AB: Sure.

MS: Which comes to us as history, when we know what’s going on these days.

AB: Mm-hm.

MS: – – I went to talk for a few days in a bad journal school, as your – – were calling it. And these kids were interested in poetry, please. So what I did was read them a people like Bill Stafford.

AB: Mm-hm.

MS: – – at that time was a native American. But anyway, so if it was, I wanted them to have poems that sounded like the world they say outside their very window.

AB: Yeah.

MS: And that’s brought a connection immediately with the poem. And that, and that work – – would not have worked.

AB: Right. I guess my last question for you would be, this collection and many of your collections focus on animals and nature and walking. Can you talk a little bit about why certain animals are appealing to you and why, which ones you like to write about?

MS: Well, um, yes, in two ways. Shelly has a wonderful epigram that I’m using in collection of essays that might be out next year, I don’t know when it will come out. Old essays. He talks about what it’s like if there’s nobody that really you could talk to, or agree with, or argue with. You’re lonely. And I had a lonely childhood. The other girls in the early ‘50s in Ohio did not think about being poets. They were supposed to be thinking about boys and home economics.

AB: Right.

MS: So it was lonely. But he sensed the natural world will have a consciousness with your conscience. It will be company and apparently, he thinks this as if it certainly happened to him. And his father was very political and conservative and Shelly of course was not. But it gives you a sense of having a place and possibly you write poetry because you’re talking to yourself. The only thing I can say about a particular animal, it’s the whole arena of the natural world that attracts me. But everything I’ve written I’ve started with an actual encounter. I spent a lot of times in the woods. And uh, I’ve always felt the physical, the actual what I see, the experience leads me to this more mysterious infinity with the whole natural world and that’s what with every animal I uh, even when I’m humorous of. I know somebody gave me a white – – pinecone. They found it in some scat of a grizzly bear. Washed it up and gave it to me. It went through his body; it went through my body too.

AB: Oh my gosh.

MS: I thought that was proof of my close feelings – – .

AB: Sure. That’s commitment.

MS: Yeah, well – – a little piney. But there are no, really special, special animals. I think the highlight of my life was being in India and seeing tigers and a couple of tiger cubs, which is pretty unusual, but I have never written about it. I write about is common, what I see often. I’ve always done that and a few other subjects as well.

AB: Yeah. Well I just want to thank you again for speaking with me, it’s such an honor.

MS: It’s an honor for me and pleasure. Thank you. Thank you very much.