-

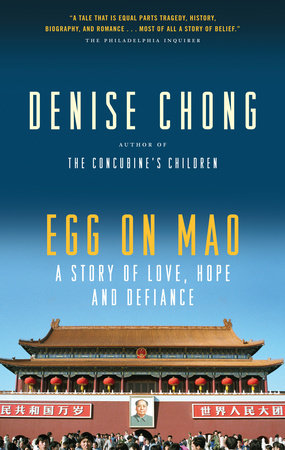

$19.95

Aug 30, 2011 | ISBN 9780307355805

Buy the Paperback:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Believe Nothing Until it is Officially Denied

A Most Extraordinary Ride

We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I

America First

The Power Broker

Sage Warrior

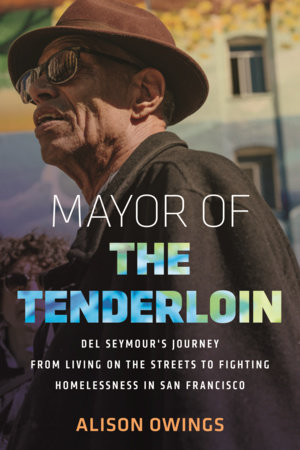

Mayor of the Tenderloin

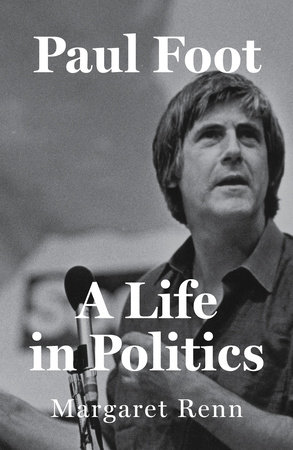

Paul Foot

Lula

Praise

Praise for Egg on Mao:

“Extraordinary . . . useful, timely and devastating . . . as insightful about everyday China as anything I have read. . . . A coming of age memoir, a suspenseful action tale and a prison documentary—all of them handled with astonishing adroitness.” —John Fraser, Literary Review of Canada

“Chong is a masterful storyteller. . . . Egg on Mao is a lovely and fascinating look at not only China, but also the power of friendship and human decency.” —Quill & Quire

“Egg on Mao speaks the universal language of human rights.” —The Daily News

“Exquisite. . . . This is a gem of a book, strong in its treatment of substance, superb in its expression.” —Winnipeg Free Press

Praise for The Concubine’s Children:

“Beautiful, haunting and wise, [The Concubine’s Children] lingers in the mind like a portrait one returns to in a family album, and elicits the same mysterious response of love, melancholy and pride.” —The New York Times Book Review

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In