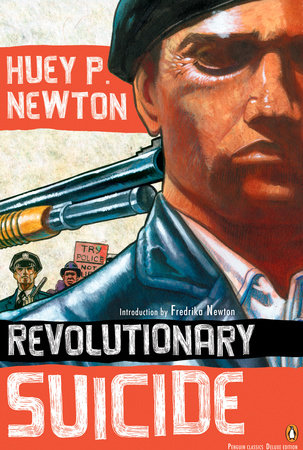

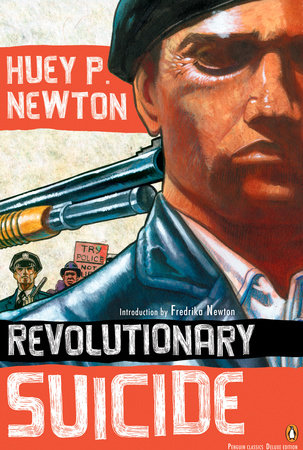

Revolutionary Suicide Reader’s Guide

By Huey P. Newton

INTRODUCTION

The year is 1966. The Beatles go on their last concert tour. The number of American soldiers in Vietnam crests 380,000. Ronald Reagan is elected governor of California. And, in Oakland, California, a self-educated, twenty-four-year-old black man, in partnership with his friend Bobby Seale, forms the radical Black Panther Party. The name of that young man was Huey P. Newton, a clever and charismatic figure whose revolutionary career and legacy continue to stir strong interest today, not only among historians but for anyone seeking to understand the conflicts and paradoxes of race relations in 1960s America. Of all the dynamic forces of the decade, few were more controversial and polarizing than Newton’s Black Panthers. To the white establishment, the Black Panthers were an armed menace to the established social order. To the black people in the communities they served, the Panthers were a more positive force—the purveyors of free breakfasts for schoolchildren, furnishers of protection for would-be victims of police brutality, and a source of hope and heightened consciousness for all.

Seven years after co-founding the Panthers, Newton told his own story in the fascinating, turbulent memoir, Revolutionary Suicide. Both autobiography and radical diatribe, Revolutionary Suicide tells of Newton’s life up to the age of thirty. Beginning with his birth as a minister’s son in Louisiana, the book follows him through his disheartening years in the Oakland public schools and his brave, independent struggle to raise himself out of illiteracy. It also narrates his sudden ascendancy to notoriety as a social and political leader of the Far Left—a status both enhanced and endangered when Newton is placed on trial for the murder of a police officer.

Apart from its significance as a political document, Revolutionary Suicide is the affecting story of an American life, evoking the exuberance of childhood, the pain of adolescence, and the alienation of a dispossessed adulthood. Yet it is in its observations of social inequality, its indictments of white authority, and its recommendations for radical reform thatRevolutionary Suicide leaves its most lasting impressions. Openly denouncing white America as the enemy, and averring that “to die for the revolution is heavier than Mount Tai,” Revolutionary Suicide calls upon all African Americans to unite in resistance to a faceless, bigotry-ridden system. While arguing the importance of dying for the cause of liberation—the revolutionary suicide alluded to in its title—Newton’s memoir raises an inescapable parallel question: In a social situation whose logic evidently presses toward physical and spiritual death, what are the possibilities for life and survival?

In Revolutionary Suicide, Huey P. Newton recalls a wide range of emotions, from anger to pride to a passionate love for a people and an ideal. Perhaps the only feeling absent is fear. The man who addressed us in these pages may be, depending on one’s perspective, a criminal or a hero. But in either case, Newton stands forth as a man who will never surrender, living his life with an unconquerable dignity that even his detractors must honor.

Born the son of a Baptist minister in 1942 in Monroe, Louisiana, Huey P. Newton moved to Oakland, California, with his family at the age of three. Although functionally illiterate upon graduating from high school, he taught himself to read by studying Plato’s Republic. Newton enrolled at Oakland City College, where he campaigned successfully to have black history included in the curriculum. While at the college, he became familiar with the writings of Marx, Lenin, Frantz Fanon, and Chairman Mao. In 1966, with Bobby Seale, Newton co-founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, an organization in which Newton served as minister of defense. Though perhaps best known for their community street patrols, which openly displayed loaded firearms, the Black Panthers also sponsored breakfast programs for poor children and provided shoes and health care for the needy in the black community. Convicted in 1968 of manslaughter in the shooting death of Oakland police officer John Frey in 1968, Newton spent more than a year and a half in prison before his conviction was reversed. After a series of mistrials, the case against Newton was voluntarily dismissed. After reaching its high-water mark in 1970, when it claimed several thousand members, the Black Panther Party steadily declined, undermined in part by the efforts of the FBI. Accused of another murder in 1974, Newton jumped bail and spent the next three years in Cuba, after which he returned to the United States to stand trial and was acquitted of the charge. Newton earned a doctorate from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1980. He was shot to death by a gang member in 1989.

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In