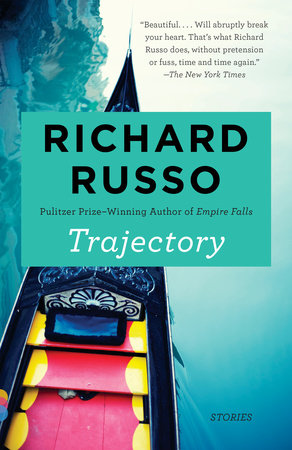

Trajectory

By Richard Russo

By Richard Russo

By Richard Russo

By Richard Russo

By Richard Russo

Read by Amanda Carlin, Arthur Morey, Fred Sanders and Mark Bramhall

By Richard Russo

Read by Amanda Carlin, Arthur Morey, Fred Sanders and Mark Bramhall

Part of Vintage Contemporaries

Category: Literary Fiction | Short Stories

Category: Literary Fiction | Short Stories

Category: Literary Fiction | Short Stories | Audiobooks

-

$16.00

Apr 03, 2018 | ISBN 9781101971987

-

May 02, 2017 | ISBN 9781101947739

-

May 02, 2017 | ISBN 9780451486462

487 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Picked-Up Pieces

Half a Life

Time to Be in Earnest

Spring

God’s Silence

Breathing Lessons

Thank You, Mr. Nixon

Killer’s Choice

Home/Land

Praise

“Beautiful. . . . Will abruptly break your heart. That’s what Richard Russo does, without pretension or fuss, time and time again.” —The New York Times

“[A] collection of short fiction so rich and flavorsome that the temptation is to devour it all at once. I can’t in good conscience advise otherwise.” —Laura Collins-Hughes, The Boston Globe

“Has the engaging quality of tales told by a friend, over drinks, about a person we know in common. And so we lean forward, eager to hear what happened next.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Vibrant. . . Russo’s gift for character is as powerful as ever, enlivened with spot-on detail.” —People

“The four tales here are replete with Russo’s insightful studies of relationships. . . . Throughout, we enjoy Russo’s skill at weaving a story in which conflicted characters find moments of revelation and, sometimes, redemption. . . . . Rewarding and worth ruminating about.” —Minneapolis Star Tribune

“The stories in Trajectory are classic Russo, tales of minor-key defeat laced with rue and humor. . . . Russo again shows how adept he is at portraying life as a tragicomedy. . . . Gives readers plenty to enjoy and mull as his characters ponder their life trajectories.” —The Dallas Morning News

“Delightful. . . . Unearthing such insight on page 44 (instead of page 444) is a bit like watching a successful squeeze bunt score a runner from third—just as exciting as a home run, but a shorter trip and a rarer treat.” —Paste

“Intriguing and universal. . . . Russo newcomers will begin to scope out why he’s a Pulitzer Prize winner.” —Houston Chronicle

“Heart-warming. . . . Absorbing. . . . A testament to Richard Russo’s skill at deploying his characters. . . . All four stories are challenging not because they are difficult—they are not—but because they raise questions about why we live our lives the way we do, and if that’s all right.” —The Washington Times

“[An] engrossing collection.” —Southern Living

“Russo remains an entertaining and interesting writer.” —The Christian Science Monitor

“Russo is a master at Everyman, offering common folks doing their best to get by, the cards often stacked against them. . . . This collection is a welcome edition to Russo’s work—if you haven’t delved into the Pulitzer prize-winning author’s books, do yourself a favor and begin.” —The Missourian

“Cogent, wry and satisfying. . . . Confirm[s] Russo’s status as one of the most justly celebrated American writers.” —Portland Press-Herald

“Wonderful. . . . Russo’s writing should be cherished.” —Columbus Dispatch

“Powerful. . . . An entertaining and compellingly provocative read.” —New York Journal of Books

“Potent and surprising tales. . . . Russo rarely wastes a word, interweaving details and dialogue into master classes on storytelling.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred)

“A singularly satisfying journey. Very few writers so thoroughly embrace human foibles, or present them in such an accepting and empathetic manner.” —Booklist (starred review)

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In