The Unsettled

By Ayana Mathis

By Ayana Mathis

By Ayana Mathis

By Ayana Mathis

By Ayana Mathis

By Ayana Mathis

By Ayana Mathis

By Ayana Mathis

By Ayana Mathis

Read by Bahni Turpin

By Ayana Mathis

Read by Bahni Turpin

Category: Fiction

Category: Literary Fiction

Category: Fiction

Category: Fiction

Category: Literary Fiction | Audiobooks

-

$18.00

Jun 04, 2024 | ISBN 9780525435617

-

$31.00

Oct 17, 2023 | ISBN 9780593793039

-

$29.00

Sep 26, 2023 | ISBN 9780525519935

-

Sep 26, 2023 | ISBN 9780525519942

-

Sep 26, 2023 | ISBN 9780593788424

687 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home

Zero-Sum

Before We Were Innocent

Life and Other Love Songs

A Little Life

Sisters of the Lost Nation

The Rainbow

Sea Change

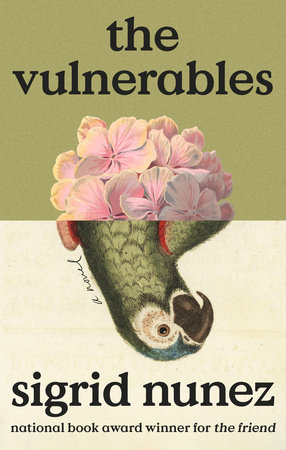

The Vulnerables

Praise

A BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR: The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Oprah Daily, Kirkus Reviews

“Poignant, heartbreaking . . . Mathis skillfully and subtly drops allusions to historical events, sending the reader on a kind of intellectual treasure hunt.” –The New York Times Book Review

“The Unsettled follows Ms. Mathis’s debut, The Twelve Tribes of Hattie, whose loosely assembled family vignettes also explored the ambivalent aftermath of the Great Migration north. But this is a far better book, more focused and cohesive, and also more alive.” –The Wall Street Journal

“Ten years after The Twelve Tribes of Hattie, Mathis again strikes story-telling gold.” –People

“An ardent, ambitious, and carefully stitched tapestry of a novel, one that deserves and rewards our attention.” –The Minneapolis Star Tribune

“The Unsettled is a powerful, moving novel about the fracture of Black family and the attempts we make to suture it, about the power of our history and futile attempts to sanitize it, about the connection of Black people to the lands they fight so hard to keep, and the government’s attempts to separate them from it.” –Roxane Gay, The Audacity

“A decade after taking the world by storm with her debut novel, The Twelve Tribes of Hattie—the 72nd Oprah’s Book Club selection and an instant bestseller—Mathis is back with a highly anticipated and emotionally propulsive follow-up . . . Through a chorus of distinctive and virtuosic voices, we gather the story of a mother, a daughter, and the land that both unites and divides them.” – Oprah Daily

“[A] masterpiece . . . The Unsettled is poised to be a significant addition to contemporary literature, affirming Mathis’s status as a gifted and influential voice in the literary world . . . An emotionally charged journey through the intricate tapestry of family, love, and the relentless pursuit of belonging.” – Essence

“Important . . . The Unsettled bears within its title the affective work that it accomplishes. Through entanglements of generational memory, placemaking, loss, nostalgia, family, community, and social dissolution, the reader is dislodged from the comfort of neat resolution.” –Los Angeles Review of Books

“Shelter without the grace of welcome is exposure to the worst coldness of the world. Loyalty and the offer of comfort satisfy needs we feel in our bones. In The Unsettled, Ayana Mathis brings these extremes of experience intensely to life. This is a fine, powerful book.” – Marilynne Robinson, author of Gilead

“The Unsettled crosses generations and landscapes, digs in the Southern soil and walks mean Northern city streets. Expansive and explosive, this beauty of a novel showcases Ayana Mathis’s grace on the page, as writer, as storyteller. A book to be read and re-read.” – Jesmyn Ward, author of Let Us Descend

“Ayana Mathis is one of the most brilliant writers working in today’s America. A tour de force, The Unsettled is a poetic and fierce study of the conflicts between circumstances and personalities, between dreams and survivals, between the indifference of the world at large and the passions of individuals.” – Yiyun Li, author of The Book of Goose

“Outstanding . . . Perfectly paced . . . A heartbreaking tale about Reagan’s America that deftly weaves the past and present into the possibility of a bright, if still-unfolding, future.” –BookPage (starred review)

“Another triumph for Mathis . . . Fresh, bold, entrancing . . . [The Unsettled] sparkles even as it cuts to the bone.” –Library Journal (starred review)

“An affecting and carefully drawn story of a family on the brink . . . Mathis powerfully evokes the heartbreak and ways best efforts are undermined by social and legal machinery.” – Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“A simmering family saga involving fraught efforts in building Black communities . . . Mathis ratchets up the tension all the way to a stunning reveal, which reunites the family members for a reckoning with the truth. Readers won’t want to miss Mathis’s accomplished return.” – Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Surprising and gorgeous . . . Mathis’ long-awaited sophomore novel leaves the Great Migration of her lauded debut (The Twelve Tribes of Hattie) for the 1980s, but her sharp characters, vivid settings, and beautiful sentences remain . . . Hattie fans will not be disappointed.” – Booklist

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In