Tracy Kidder, graduate of Harvard University and then the University of Iowa, has won the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the Robert F. Kennedy Award, and many other literary prizes. It’s hard to say what links his writings other than the fact that admirable people who do admirable things (paraphrased from his own words below) are at the center of all of them.

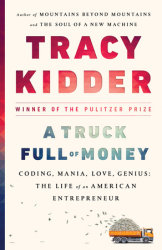

He’s written about the art of nonfiction, an immigrant from Burundi in search of a new life, and his own tour of duty in Vietnam. In his most recent work, A Truck Full of Money, Kidder writes about Paul English, an entrepreneur diagnosed with bipolar disorder who strikes gold. Below, we talk with Kidder about what inspired him to write his latest book, the American identity, and more.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: You write in the author’s note that something about Paul English made you feel that your tour guide of the world of computer software should be the subject of your next book. Can you elaborate on what exactly made you change your focus, and why you found English so compelling in that moment of changing your mind?

TRACY KIDDER: It wasn’t a matter of changing my mind suddenly, but rather something that happened over time, as I discovered just how much territory he had covered in his life. I was, at first, looking for a window on the digital age, and Paul’s career spans a great deal of it. On top of that, he had been both a programmer and an entrepreneur. More important than any of that – to me – he turned out to be interesting, more interesting than I had known. Among other things, he’d overcome a lot in his life and still struggled with bipolar disorder. For me, most people are interesting, even some of those who have worked hard not to be. I suspected that Paul would turn out to be more interesting than most, and I was right.

PRH: I was very interested in the connection you make early on between Paul and his team at Kayak and blacksmiths in 18th century Concord, in that they cared about the act of creation – whether creating a travel website or a horseshoe – more than travel itself. Can you compare that approach to your role as a writer?

TK: Well, I don’t know. Mine may be completely opposite, in the sense that what I believe really matters about a piece of writing is the final product, the piece of writing itself. How one gets there doesn’t strike me as something that ought to be of great interest to anyone, including me. That said, the tricks of the trade and especially the aims of writing do interest me. (I wrote a whole book on the subject, or more accurately helped my friend Richard Todd write one.) I’m sure that in my time I’ve published a few articles that I ought to be ashamed of, but I am not ashamed of any of my books (except the very first, which I have paid to keep out of print). And the reason I’m not ashamed is that I know that in each I did the very best I could at the time.

PRH: You write that there is an aspect of the American identity that believes ‘consistency doesn’t mater. Only innovation maters,’ and Paul English exemplifies this idea. Do you agree with this idea yourself? In studying the New Economy and those who have won and lost in the tech world, what do you think are some downfalls of being so, as you write, ‘unencumbered by the past’?

TK: You don’t have to do what your father did – I think that is probably the best way to express this strain in the American ethos. It’s an old doctrine, also present in Emerson’s often quoted line: “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” (I think I have that right). Obviously, one could take this dictum too far. It might easily be a recipe for recklessness with other people’s money, for instance. I’ve read some of the biographies of tech titans, hagiographies in some cases, but I have no idea whether or not it’s been useful or a detriment for the entrepreneurs of digital technology, or whether they practiced it.

I do believe it is a useful dictum for an economy in the long run, and of obvious utility for some people in some situations. But to the extent that Paul embodies this strain of the American ethos, he also embodies its counterpart. That is, he is also capable of working for a long time and with great energy and zeal on a single project. So I think the general prescription runs like this: You try out an idea. If it becomes clear that it’s not going to work, you jettison it without hesitation or remorse. If, however, it becomes clear that it’s going to work, you dig in and make sure that it does.

PRH: Looking at your oeuvre, is there a question that links all the books you’ve written so far, and if so, what is it? Did A Truck Full of Money get you any closer to an answer?

TK: I used to think there was a common thread, which was work – stories of Americans at work. But that ended sometime back, I think. The only thread I’m aware of, consciously, is characters. Not famous people as a rule but people interesting in themselves who are doing something interesting. If I find the right character, I feel sure I’ll find a good story.

PRH: Your books are often about people who are honest, generous, and kind. Is it difficult to write about genuinely good people and keep the narrative interesting and the reader engaged? Are you ever afraid during the reporting process that you’re going to learn something about your subject that will tarnish your opinion or compromise the book? If you’ve had that happen, how have you handled it?

TK: It is true that I’ve written about admirable people as a rule – people who have admirable qualities and do admirable things. I do think it is a bit more challenging to write about human virtue than about venality and evil, which are somehow much easier to believe in. But none of us is perfect, and I hope I’ve never sugar-coated a character or a story. I want to depict real people as accurately as I can.

PRH:Paul English has bipolar disorder and partial epilepsy. At one point you ask “had (Paul’s hypomania) helped him in his role of entrepreneur, boosting his energy and boldness? Or had he made his way in spite of hypomania?” After covering the tech world for several decades, do you see a relationship between mental illness and technological brilliance? How do you answer your own question about Paul?

TK: I think it’s dangerous to imagine that mental illness is somehow a necessary ingredient for creativity in any arena. It may be true, as Paul English and others suggest, that first-rate computer programmers tend to be socially awkward but that is hardly evidence of mental illness. I think that the hypomania which Paul suffers from has endowed him with special capactities. For instance, it allowed him, and perhaps impelled him, to work intensely for long periods without much sleep. But it also had its down side. At times it boosted his confidence, but sometimes misled him into embracing a loopy project that he would have rejected when free of hypomania. I believe that at bottom, the source of his genius lay elsewhere.

Another way to say all this is that we are all born with talents and challenges. How we deal with those is perhaps the real test of a person’s achievements in life.

Yet another way to say all this is that it’s a bad idea to generalize about any group of people. You’re bound to be wrong more than half the time.