Author Q&A

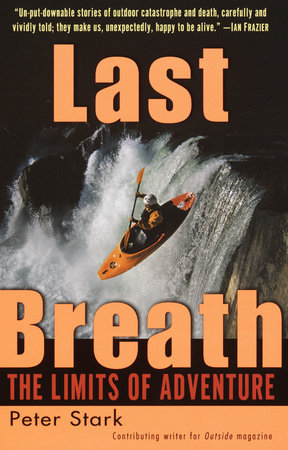

Q: Why did you choose Last Breath as the title of this book?

A: The stories in the book are all essentially about the final moment just before one dies. I chose “Last Breath” because it implies a certain kind of desperation at that moment yet at the same time a certain possibility of understanding. The story that perhaps best exemplifies this is the one about a group of women climbers who get stuck in a snowstorm while ascending Annapurna in the Himalayas near the Tibetan border. One of the women in the group has been showing symptoms of mountain sickness. As they weather the storm in a hastily constructed snow-cave the health of the stricken climber continues to deteriorate and she succumbs from a High Altitude Cerebral Edema. Like many of the stories in the book this one has a strong spiritual component, in this case a Tibetan Buddhist theme. According to the beliefs of Tibetan Buddhists, the “art of dying” is as important as “the art of living” and it is in the final moment of death–that moment of the last breath–that one can achieve enlightenment.

Q: And why do you call these stories “Cautionary Tales”?

A: For some of the characters in the book it is their own fatal flaw that brings them to the brink of death, but for most of the others it is an accumulation of small misjudgments or even, in some cases, circumstances beyond their control that conspire to put them in dire situations. I used “Cautionary Tales” to underscore the notion that when you’re in wilderness situations you’re constantly calculating how far you can go; how far you should go. It’s also meant to be a warning sign that says, “You’re on your own here. You’re making your own judgments.” In the wilderness the line between safety and life- threatening danger is often a fine one, and it shifts all the time depending on the circumstances, the individual, and the extent of that person’s confidence level.

Q: Is this book purely about death?

A: In a way this is a book about life as much as it is about death because the people who put themselves in extreme wilderness situations are embracing the outdoor world, and the extreme outdoor experience, for its intensity. The outdoor activities described in Last Breath, such as free-solo rock climbing (without ropes, anchors, belays, or any other form of protection), or kayaking in a raging river’s cascade of foam and noise and spray, make one feel so alive and focused and in the moment. They make you appreciate the fact of simply living and breathing and being there–particularly if you find yourself caught in a desperate situation and then manage to extract yourself. Afterwards every beam of sunlight, every breath of air, every step taken, seems a gift.

Q: How did this book originate?

A: I’ve been drawn to outdoor activities since I was four years old when my grandfather and father took me on my first wilderness canoe trip. As an avid outdoorsman I’ve always been interested in determining just how far I can go. When I’m actually out in wilderness situations I ask myself what’s too far? At what point do I get scared? How can I die out here? What would happen if it all went wrong? What mistakes could I make that might lead to a fatal mistake? What would my chances be of escaping from the situation? And, if I were about to die, what exactly would be happening to my body? And what would I be thinking about?

I’ve also always been particularly intrigued by snow and ice and cold, perhaps because I was born in January in Wisconsin and always considered winter “my” season. After traveling to and writing about the Arctic in my previous book, and seeing how amazingly adaptable the Inuit people are to the brutal cold of their climate, I proposed a story to Outside magazine in the winter of 1996 about the physiology of the human body in extreme cold. My editor at Outside suggested I make it a story about a fictional character who freezes. I immediately liked the idea and saw what great possibilities it would open up, both in terms of devising a compelling plot and in terms of illuminating the physiology of the human body in the extreme cold. It also tapped into my interest in the question of how far is too far? In this case, how far can you go in the cold before you’ve gone too far?

The article I wrote–about a cross-country skier who gets caught in the woods in thirty- below-zero temperatures–became the seed of Last Breath and now, slightly altered, serves as its first chapter. When it ran in Outside in 1997 it immediately struck a nerve with readers. It was widely reprinted in other magazines, anthologized in a college textbook on writing, and later cited as one of the “Notable Essays of 1997” in Best American Essays 1998. This all got me thinking it might be interesting to explore the psychological and physiological changes other characters might experience in a wider range of extreme outdoor situations.

Q: What sort of research did you do for this book?

A: I talked to literally hundreds of outdoor adventurers who had been caught, and almost died, in situations similar to the ones described in Last Breath. I talked extensively with doctors who specialize in the kind of medicine that applies to those situations–for example, high altitude medicine. And I read tremendous numbers of medical journal articles and textbooks as well as survivor accounts. One way of doing this book would have been to tell the stories of actual survivors and trace what happened to them and their physiology as they hovered on the brink of death. That approach seemed very limiting so I choose instead to use composites of characters drawn from the many experts and survivors I spoke to.

Q: Which of the situations that you outline in Last Breath grew out of experiences you had while traveling to remote places with your wife and kids?

A: In the summer of 1996, while I was writing the hypothermia story, my family and I traveled to Bali. We then flew two thousand miles west to Irian Jaya to go trekking among the tribes of the Highlands. Some Western researchers had recently been kidnapped there by a guerilla group demanding independence from Indonesia, and had been held for four months until they were rescued, unharmed. This made me nervous, especially with Molly along, who was two years old, though I had the assurance from some reliable Irianese sources that there was no danger of our being kidnapped. Nevertheless, the threat of capture in some far-off land where you don’t know what’s happening or why helped inform the dehydration chapter where the character is left out in the desert with a single goatskin of water by nomad guerillas. An experience with what we thought might be malaria during that same trip is one of the reasons the book includes a malaria chapter.

The dehydration chapter was set in the Sahara Desert because we’d traveled there with children, too, when Molly was four and Skyler only five months. We were driving to an oasis about 50 miles into the desert when we got caught in a sandstorm. Though the road was good, the sand was blowing so hard it was like a haze that literally sandblasted the paint off the front of the car. I realized we had no water with us, other than a half-liter or so, and I kept thinking if we broke down now, or couldn’t drive due to the sand, or somehow got lost, how long would we last? It was spooky, and I realized how unprepared we were for the environment we were entering, even though we were really only on the edge of the desert with a comfortable hotel not far in front of us.

Q: Have you ever faced death yourself in the way your characters have?

A: Not to the degree they have but I’ve certainly been in situations where I’ve thought, “I could easily die right here.” I’ve stood at the top of countless avalanche slopes, like the snowboarders in chapter four, wondering whether I should ski the slope or leave it alone. One time, when I was much younger and didn’t know what I was doing, I was on such a slope with a buddy who was even more ignorant than I was. Fortunately I knew just enough to recognize the dangerous conditions. I stamped hard on the ground and a small avalanche began right below my feet. It was big enough to have buried us if it had started above us on the slope. I’ve also been caught in big holes in white water, like the kayaker in chapter two. And I know what it’s like to be really cold. For all the deadly scenarios in Last Breath, I have at least some feeling of how you get into it, how it starts. I could have easily come up with hundreds of strange ways to die, indoors or out, but I consciously chose situations that are fairly common in the outdoors so readers will have a better chance of understanding situations in which they might easily find themselves.

Q: How have our attitudes towards death, particularly in Western society, changed over the years?

A: A century ago death commonly visited the bedroom next door. It was here that a relative or grandparent would die of sickness or old age, in the midst of the household. Death then was a part of everyday life. Today we don’t see death in that day-to-day way. And we certainly don’t talk much about it. Instead it is whisked away to the sanitized environment of the hospital where advances in technology and medicine allow us to keep it even further at bay. In contrast to many societies that are less technologically developed than ours, we’ve removed death from our everyday lives. As a result we’re both frightened of it and curious about it. That might be one reason why there’s so much violence and killing in our movies and on television–because we’re obsessed with this thing that has been so far removed from us.

Q: Were any of the stories in Last Breath particularly hard to write?

A: Not really. Even though it’s about death, the book was fairly easy to write because I was so interested in what was happening to these characters, and the situations in which they found themselves. And of course some part of me is in every one of the characters and situations. The one thing that caused me difficulty, and that I consciously stayed away from, was the notion of bringing children into the stories. I made no attempt to place children in dangerous situations in the outdoors, nor did I create any characters who were parents of children. I have two small children of my own and that would have been too difficult for me.

Q: What do you think will most surprise readers of this book?

A: I think readers will be surprised to find that, despite the dying and the grisly descriptions of physiological processes, this is a life-affirming book, and that these situations are in many ways life-affirming situations. I also think readers might be amazed at how ingeniously the human body adapts to the constant changes in its external and internal environment–to changes in air pressure and oxygen, to food consumption and water intake, to increased physical workload, to heat, to cold, to fear and blood loss. Yet that resiliency can be misleading. The human body, in many ways, is as delicate as a hothouse flower, capable of existing in only an extremely narrow band of conditions.

Q: Which of the deaths you describe do you fear most?

A: The one that I found most unpleasant, from a physiological point of view, was the death through heat stroke. What happens with heat stroke is that your body literally cooks from within. One of the reassuring aspects of this book is that by the time you get to the point where you’re really on the brink of death–whether from heatstroke or hypothermia, drowning or mountain sickness–you’re totally out of it. If you survived you’d remember nothing. In this way the body provides its own protective mechanism. It protects your consciousness from being aware of what’s going on.

Q: Why do you include a cautionary paragraph at the beginning of the book?

A: I’ve made every attempt to insure the accuracy of the physiological processes and medical treatments portrayed in the scenarios here. But I wanted to underscore to readers that this book is to be read for fun, not as an instruction manual for diagnosis or treatment. I certainly wouldn’t want anyone using it to diagnose what’s wrong with their buddy sleeping in the tent next to theirs the next time they’re out on a camping trip. If that’s what readers think they might need, they should choose from among the many available instruction manuals and textbooks dealing with wilderness medical emergencies–several of which are listed in the sources section at the back of the book.

Q: How would you describe the characters you created? And how did you come up with them?

A: When I sat down to write the book I knew I wanted to create a variety of situations, characters, and voices. I didn’t want every character to be the same. Some are wholly sympathetic; others are flawed in some way that leads to them making mistakes. And of course there’s one character–the rock climber–who is a complete jerk. This was a character that sort of suggested itself. Not all rock climbers are hyper-competitive but there is a certain level of rock climbing that is extremely competitive. So I started thinking, if my character were a really competitive rock climber, what would his real life job be? The most cutthroat job I could think of was a corporate takeover artist. Then I tried to create a corporate takeover artist of the worst kind. This is a guy who’s constantly calculating the odds and thinking he’ll always be able to come out on top. Unfortunately he finds himself in a situation where the odds catch up with him.

Q: Which of these stories gets the biggest reaction?

A: The cerebral edema chapter, about the all-women climbing team, has gotten a lot of reaction from people who have read the book. I think one of the reasons is that there are six characters in the story (five of whom are responding to the sixth dying slowly in their midst). The interactions among them allowed me to explore how different people deal with death in different ways. And because there were so many characters, readers could find in at least one of them something with which they could identify. This was also a chapter that touched me emotionally as I wrote it. I wanted the characters, and the situation they found themselves in, to be as sympathetic as possible. I had this vision of them being five midwives around this dying woman. But instead of bringing a baby into life they’re helping her pass as peacefully as possible into death. That was the image I started with. I also made one of the characters, from whose point of view you see the story, a practicing Buddhist. This helped me explore the way different societies, cultures, and religions view death.

Q: How has working on this book changed you?

A: Writing this book has reinforced my sense of caution when I’m in remote places, and the sense that I can turn back whenever I want. I no longer feel like I have to keep charging on ahead when I get into difficult situations. It has also changed my attitude toward the outdoors and risk and death. You’d think the opposite would be true but there’s something about having a greater familiarity with death that is strangely reassuring. I think that’s something a lot of other cultures know but that we’ve largely forgotten. We do have religious-based rituals during times of death, but we also have a tendency to stay away from the kind of intimacy with death that other cultures display. For example, the Japanese calmly prepare for their demise with a centuries-old tradition of writing in their last days or moments what are known as “death poems.” In Tibet, those who are dying have read to them The Tibetan Book of the Dead, which is an intimate portrayal of the process of death and the opportunity it presents for liberation.

Q: Some critics might suggest you’re somehow exploiting death. What’s your reaction?

A: Death is clearly a difficult, emotionally laden topic. I guess you could say I’m exploiting it but I’m exploiting it in the same way we exploit anything we experience: as a means of learning something new.

Q: What do you want readers to get out of this book?

A: I hope this book will, in some way, change their attitude toward death. I want to make it something less fearful. I also want readers to understand there are a lot of ways we can live our lives. We can put ourselves in situations of greater or lesser risk. We all make those choices. I want readers to see there’s something to be learned from making those choices and putting ourselves in those situations.

.