Author Q&A

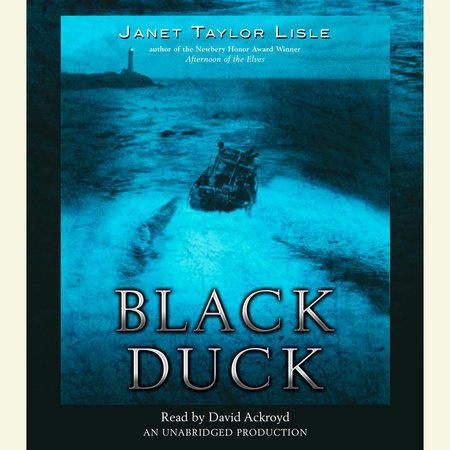

In the Notes of Black Duck, you stated that the story came to you through a memory of your father’s and that the story is based on a true event. Tell us more about how this true story was relayed to you to enable you to tell it so vividly—your father’s input? through your own research?

My father was eight in 1929, the year the rumrunning boat Black Duck was fired on by a Coast Guard cutter across our bay, near Newport, Rhode Island. He knew little of this particular incident first-hand. Stories of smuggling and rum runners were everywhere in his coastal community, though, and he and his pals had sharp ears. A few hundred yards from Dad’s family house, at the end of a rural lane, lay a beach where he often swam and played. The place was visible from his bedroom window, and it was here, he later told me and my brothers that, waking late one night, he saw an eruption of lights and action. Rumrunners! He knew them at once and never forgot the dark thrill of watching that secret, illegal landing.

If I were to point to a single spark that ignited the writing of the book Black Duck, this would be it. My father’s memory touched my imagination in a most visceral way. As a child, I knew the lane and the beach. (I know them today.) I saw the dark figures my father described, the incoming boat, the flickering headlights. I felt, and never forgot, his excitement.

A few years ago, I became interested in the Black Duck shooting as a part of Rhode Island’s colorful Prohibition history. After reading newspaper articles from those times, I knew I wanted to write about them. But history, even if it has taken place just across the bay, is a distant thing. Live memory is quite another. In the end, it wasn’t the research I did, but the landing my father witnessed as a child that made this story luminous and real in my mind. Armed with his eyes and memory, I could write the scenes close up, as if I’d been there, because in a way I was.

Since your career began as a journalist it’s not surprising tha the premise of this story was very appealing: a budding journalist hunting down a story, and the use of articles about the event interspersed. How did you come to use this approach?

Actually, Black Duck was written unframed in the first couple of drafts. That is, the character of the young would-be journalist David Peterson didn’t exist, and neither did the old Ruben Hart. The novel opened with the boys Jeddy and Ruben discovering the murdered body on Coulter’s Beach, and the story proceeded as a straight, third-person narrative. Three quarters of the way through the writing though, I ran into a dead zone. Every writer knows these places. They’re where the tension collapses, the story’s forward motion stops, the characters droop and the writer falls asleep at his/her desk out of sheer boredom.

Dead zones mean something is wrong with the plot. To go forward, you may have to go back and rework things. When I went back, I saw that what my story needed was more perspective. It was too one-dimensional, just a bunch of episodic adventures, like a comic book. I experimented around and finally discovered that if I reframed the narrative, I could move it again and give it deeper meaning. So David Peterson was born, and I was able to use my own experiences as a young reporter to fill out his character. With him also came the old Ruben Hart, a character who immediately fascinated me. His voice became the voice of the novel. From there on, I had clear sailing to the end.

What do you find are the challenges of writing historical fiction as opposed to a story with a contemporary setting?

The main difficulty with writing historical fiction is the danger of historical fact pile-up. A lot of historical fiction I read seems to suffer from this. After reading about and researching an era, a writer tends to want to put everything he/she has learned into the book. I’m no exception. I want to show off what I know and make sure my readers “get the feel” of whatever olden time I’m into.

That’s the trap. Too much historical detail is a killer to a novel. (Too much contemporary detail would have the same effect on a contemporary novel.) Facts weigh down fiction. The characters can’t move; they’re crashing into the set design and wearing too much period clothing. I’ve come to believe that readers can get more history from the voice of a story than from larded-into-the-text descriptions of old-fashioned ways.

I do the research and take the notes and revel in the amazing details of history as much as anyone, but when it comes time to write, I try to put all that aside. The story comes first. I let the scenery fade into the background, where it belongs.

You have some wonderfully drawn characters in this story, even the more minor characters have a lot of presence. I especially liked the relationship between the two boys and the very emotional side of their friendship as they struggled to do the right thing. Can you talk about this struggle as a theme in your books?

One of the strange truths I came upon growing up is that the rock-solid, old-fashioned Truth I was taught to admire and aspire to as a child doesn’t really exist. There is no truth, no law, no absolute understanding of a situation that is always right. Exception is continually tempering the rules. If you are a realist, you must pick and choose your moral high ground, and even then be ready to shift as new facts come in.

Many of my books are woven with threads of these human dilemnas: What is right? What is wrong? What to do when two rights collide? In my novel Afternoon of the Elves, Hillary steals food from a store to help her friend who is in need. Is this right? In The Art of Keeping Cool, Robert reports suspicious spying activities of the German painter Abel Hoffman to the police. But man is innocent and this action leads to his death. How should Robert feel?

Black Duck paints the problem of belief in Truth, the Always-Right kind, in starker colors. Ruben’s friend Jeddy commits a betrayal of the most egregious nature because he can’t see how to shift his ground, how to weigh truth against truth and come out on the right side. It’s Ruben’s special agony to have to witness this failure and the havoc it causes, and to try to forgive his friend.

This story is very visual. Do you have thoughts about your books becoming or compared to films?

If Black Duck were to become a film, I’d go to see it and probably be disappointed. Books often don’t translate well to the silver screen, at least in the eyes of their authors. This is understandable. We writers have an array of voices, pacing strategies and literary techniques we use to bring our stories to life, and these are very different from the camera angles and editing techniques a film’s director must employ to get his screen effects. These differences affect the content of a work as well. Subtleties of plot and characterization that I might consider essential to my novel might be scrapped or reinterpreted by the film’s scriptwriter or director in the interest of making a box-office success. Even if I were the script-writer, there’s no guarantee my novel would remain intact, as many authors have discovered. Occasionally a novel is translated well into film. I think the movie To Kill a Mockingbird is tremendously evocative, and a fitting extension of Harper Lee’s novel.

How did you become an author of juvenile fiction?

There really isn’t much difference, in my mind at least, between writing ‘juvenile’ fiction and writing all the other kinds: say ‘literary’, ‘romance’, ‘science fiction’, ‘experimental’, ‘confessional’, etc. These are categories that marketers of books have cooked up to identify certain groups of readers and sell to them more efficiently. Readers themselves are notoriously free-wheeling when it comes to what catches their attention.

As a child, I read the books my parents left lying around, with no particularly bad effects. As a mother, I read books my daughter was reading in her 4th, 5th, 6th grade classes, and wasn’t disabled either. In both cases, I found interesting books and boring ones, stories that gave me something and others I didn’t bother to finish. Because the main characters in BLACK DUCK are 14-year-old boys, the book marketers have targeted the book to kids who are around fourteen, or perhaps boys who aspire to that age. I didn’t write the story to fit into that category. I’d hope that all different kinds of people would read the book, for all different kinds of reasons, and that some, from the depths of whatever category they’ve been shoved into, would come away with a feeling of satisfaction.

What authors did you enjoy as a child? Who do you enjoy reading now?

My favorite writers as a kid were: Beatrix Potter, J.R.R. Tolkien (“The Ring Trilogy”. Back then, it wasn’t famous. Tolkien was a little-known British author.) William Pene DuBois (especially,The Twenty-One Ballons). Elizabeth Speare (The Witch of Blackbird Pond.) Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped and The Mysterious Island.(Our dad liked these last two and read them to us.) Margaret Rawlings’ The Yearling. It’s great that so many of these wonderful authors’ books are still around and being read.

Now I read and admire: Cather, Woolf, Italo Calvino, Marquez, Alice Munro, E.B. White, Muriel Spark, Rumer Godden, Eudora Welty, Joan Didion, and many, many others. I also like to read poetry and biographies.

What projects do you have on the horizon?

I don’t like to tell what I’m working on. As in any good plot, there’s nothing like the element of surprise.