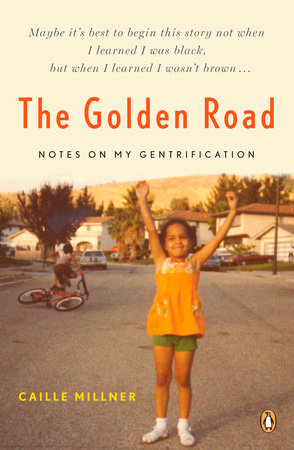

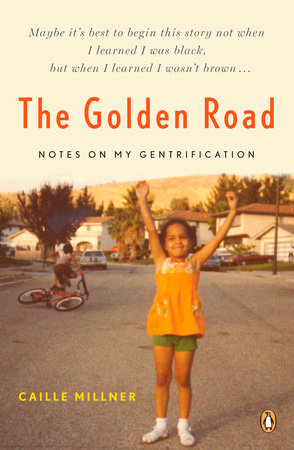

The Golden Road Reader’s Guide

By Caille Millner

INTRODUCTION

“Maybe it’s best to begin this story not when I learned I was black but when I learned I wasn’t brown,” writes Caille Millner in her memoir The Golden Road: Notes on My Gentrification. Caille, along with her brother, grew up as two of the few black kids in a Latino neighborhood in San Jose. Inundated by Cinco de Mayo festivals and birthday parties with piñatas, Caille’s only knowledge about black history in America came through her mother’s teachings. Her ancestors were American slaves, and her parents fought hard-won battles to become members of the educated, upper middle class, leaving the rural backwaters of Louisiana for better opportunities in California. Unlike her parents, however, Caille could not see America, or California, as a place of unlimited opportunity, but instead saw it as a place of continual rejection. Try as she might, Caille did not identify with the “black struggle,” nor was she a part of the Latino experience that surrounded her.

When her family moved into a new neighborhood and into even higher reaches of the middle class, Caille became even more disconnected, experiencing hostility and resentment from friends in her former neighborhood and disdain from her more affluent peers in the new one. In a search for her true nature, Caille began reading The Diary of Malcolm X and attending protest rallies; aligning herself with people on the margins of society provided some relief from her isolation.

Despite often risky behavior, Caille achieved stellar academic results which, paired with a groundbreaking article on racism at her high school, earned her entry into Harvard and launched her onto a new journey. But from Harvard to New York to South Africa, she experienced nothing more than the same sense of dislocation and despair she always had. At Harvard, it stemmed from the often infuriating hypocrisy between Harvard’s liberalism and open-mindedness and its entrenched elitism; in New York, it came from a growing unease with the city’s materialism and fierce competitiveness; and in South Africa, it struck with the stark realization that as a black woman in a country still reeling from apartheid she was powerless to change things despite her passion and altruistic intentions.

Millner’s experience in South Africa drove her back to the United States with a newfound purpose: to make peace with California, to silence the many aspects of her identity competing for her exclusive attention, and hopefully, to finally find a place in the world. There was simply no denying that, in many ways, California was home.

Caille Millner was first published at age sixteen and recently named one of Columbia Journalism Review’sTen Young Writers on the Rise. She is the coauthor of The Promise: How One Woman Made Good on her Extraordinary Pact to Send a Classroom of First Graders to College and her work has also appeared inChildren of the Dream: Our Own Stories of Growing Up Black in America. She’s received the Rona Jaffe Fiction Award, as well as prizes from the National Foundation for the Advancement of the Arts, the National Press Club, and the New York Black Journalists Association. Currently on the editorial board of the San Francisco Chronicle, she has also written for Newsweek, Essence, The Washington Post, and The Fader.

Q. The Golden Road is dedicated to your mother—obviously a remarkably resilient woman and highly influential in your life. How has she helped shape the person you are today? Looking back now, how big a role do you believe family plays in forming a sense of self as compared to external influences such as place and peers?

A. I don’t feel comfortable talking about anyone else’s family, but as far as my own development is concerned my family’s influence on me was more important than anything else. And I’d say that’s true of my brother as well. Because our family never felt at home in any of the places we lived; because we felt quite isolated especially once we moved to Almaden, our focus was internal, on each other, even when we weren’t getting along. When I look back on some of the other things that were important to me growing up—places, peers, “the culture,” as we like to call it—the way that I responded to all of those things was shaped by the values and the concerns I learned from being a part of my family.

Because her own upbringing was so unstable, my mother was completely determined to make every sacrifice that needed to be made for her own children, and she did, and I think we’ve reaped those rewards. At the same time my brother and I are both adamant about achievements in our own lives, and I think that’s partly to do with our concern for our mother. She’s already been through enough; why would we want to add to her burdens? Of course, that attitude comes with its own difficulties, but that’s what the book is about.

Q. For many years you would not even speak to your father, but you changed your mind about him the year you turned twenty-three. What changed then, and how important do you think that was in your healing/growth/evolution? How does that relationship influence you today, if at all?

A. I grew up, that’s all. In addition I’d been away from home for long enough—four years at Harvard, nearly three years in New York, and then abroad—that I was ready to let go of certain fights from the past. When I moved back to California my parents seemed like different people to me, and I simply didn’t see anything useful in clinging to old grudges. I was surprised at how eager my father was to make amends. He’d felt under siege by his own mistakes and the general patterns that my family had fallen into as far as blame goes. He wasn’t sure how he could find his way out. I suppose it was important to my healing and growth in that it reminded me of how important it is not to feel like a victim, even when things happen to you that are out of your control.

Q. In your view, there seems to be an inherent conflict/paradox within the very institutions (i.e. the elite Ivy League colleges) that can provide the so-called less privileged with opportunity for life-changing advancement. When you attend one of these universities as a sort of outsider, is what you gain worth what you might potentially lose by doing what it takes to succeed?

A. Absolutely.

Q. Many high-profile people have been in the news recently for making racially insensitive or offensive remarks. What, if anything, do you think these events, and the coverage of and reaction to them, say about our culture today?

A. Well, they certainly show how little we know each other, even after all the pain we’ve suffered in this country, all the blood that’s been spilled. After all we’ve been through here we still don’t take the time to look at each other with empathy and understanding. That’s sad.

Where there is change, though, is in people’s response to it—the fact that a lot of people get outraged or even just disgusted, when radio hosts or movie stars make vulgar comments. Whether that outrage is real or manufactured I don’t know, but it’s certainly a step in the right direction.

Q. In speaking about the article you published at age sixteen for West, the Sunday magazine of the San Jose Mercury News, you say that the retelling makes you very uncomfortable because it makes you seem much stronger than you actually are—that in actuality you are “struck dumb when confronted with racism” and therefore “hide behind a pen.” You are now a published author and writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. How do you deal with having a public persona and voice and the criticism and expectations that can come from both?

A. It can be awfully difficult. Sometimes I ask myself if I really want to write about a topic or an issue because it means I’m going to be bombarded with the worst kinds of reactions, the worst kinds of responses. There’s such a difference between the person and the work—and that’s a concept most people fail to grasp, which is why they ask questions about why artists can produce great things yet have such horrific personal lives, for instance.

Strangely enough, I think the Internet might change people’s perceptions over time. As more and more people start to have their own public personas that have little to do with their private thoughts and voices—and as they start to see what can happen as a result of an offhand remark or a small public choice—perhaps there will be a shift in our understanding. Perhaps.

Q. “There are a lot of identity narratives that would be ruined if their narrators came clean,” you write, in speaking about the identity narrative and all its inherent problems. Recently, an author of a bestselling memoir came under fire for apparent factual misrepresentations in his book. In telling a personal story, do you believe that some artistic license is allowed? What do you think the scope of memoir should be? What do you hope readers will experience in reading The Golden Road?

A. Of course artistic license has to be allowed. Memory isn’t fact. In fact you could argue that things start to lose their objective “truth,” their objective “meaning,” as soon as we remember them.

Everyone’s memory is going to contain embroideries, holes, conveniently forgotten instances, and woefully unfortunate misinterpretations. But there’s a difference between reporting something as you remember it and just making something up, even though I believe that we start to remember our own falsehoods as truth as soon as we speak them.

In my memoir, one of the ways I wrestled with this question was in the dialogue—I didn’t remember exactly what people had said to me, but I remembered the general thrust of the conversation. That’s why I chose to write the dialogue the way I did—without quotation marks, in longer passages that were designed to mimic the person’s speech patterns rather than the little bits and pieces they actually spoke to me in those scenes. This was the nearest way I could come to the truth that’s in my memory. Is it accurate? Of course not. But that’s the kind of license that readers must be willing to grant us.

Q. At the end of The Golden Road, you say you will be returning to a “home changed quickly and irrevocably and possibly not for the best,” speaking of a post 9/11 America. When you returned home, what did you in fact find?

A. That statement held true. Of course it’s always difficult to come from a society that doesn’t have many resources to one that does, especially if the wealthy country isn’t being particularly smart or responsible with what it has, but I was pretty horrified by America’s obliviousness to the larger picture of what’s going on in this country and what’s going on globally. That goes for Americans of all political ideologies—the left isn’t smarter than the right in this regard. I have only the most basic grasp of what’s going on geopolitically and I’m still horrified.

Q. Nelson Mandela is quoted as saying, “You can never have an impact on society if you have not changed yourself.” How have you redefined yourself since we left you in The Golden Road? Have you learned what to carry with you, “as we wander through the history of our lives”?

A. As usual, Mandela couldn’t be more right.

Every day I’m just unlearning more. I know less now than I did when I wrote that book, and I consider that to be a positive.

Q. Who or what inspires you today? What gives you hope or, to the contrary, concerns you most, both for your future and ours?

A. Let’s stick to hope. There’s more than enough to be concerned about it, and the only way we’ll tackle it is if we have some hope.

So when I look back at the course of the last hundred years or so in this country alone, the positive changes are quite extraordinary—civil rights and suffrage for women are just a couple of examples. If we choose the right leadership in the years to come, we’ll be up to the task of confronting the rather enormous challenges we’re up against.

So when I look back at the course of the last hundred years or so in this country alone, the positive changes are quite extraordinary—civil rights and suffrage for women are just a couple of examples. If we choose the right leadership in the years to come, we’ll be up to the task of confronting the rather enormous challenges we’re up against.

Also the positive side of globalization. A lot of people don’t believe that there is one, but there is—the growing understanding of human interconnectedness, the energy and enthusiasm that’s being unleashed from people who never dreamed that they’d ever have anything suddenly getting a chance to get out of poverty. It’s quite extraordinary to walk down a street in say, Mumbai, and talk to a kid who’s got a tiny little sidewalk shop selling cigarettes and bottled water and find out that, yes, maybe he’s living on the street, but he got out of the countryside and he found a corner to sleep on and now he’s making a few pennies to feed himself and send home to his family and that’s his dream. It’s a small, pitiful dream to Westerners but that’s the kind of dream that’s going to be fueling this world in the coming decades, and there’s something beautiful in its dignity and its humility.

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In