READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

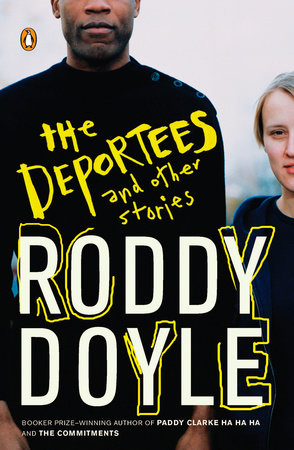

Roddy Doyle’s eight novels have established him as one of the best-loved chroniclers of the contemporary Irish experience. The toughness and charm of his characters in the face of poverty, domestic abuse, and the weight of stifling social norms have won him millions of readers around the world and have spawned three highly acclaimed films. The Deportees and Other Stories continues his winning streak in writing perceptive, poignant, and funny fiction about Ireland. For all the familiarity of Doyle’s voice and setting, however, The Deportees represents a break from his past fiction in two significant respects: the structure of the book, and the social demography of his subjects.

The Deportees is Doyle’s first collection of short stories. While his previous novels have traced the misadventures of a single character within a teeming social milieu, each of the eight stories in The Deportees has a different protagonist. What’s more, most of the stories were written in eight-hundred-word installments for serial publication in the monthly periodical Metro Eireann. These segments—six to fifteen in number, depending on the length of the story; sometimes titled, sometimes not—give the stories a pleasing built-in momentum, with a quick turnaround or mini-climax punctuating the narrative every couple of pages or so, tugging the reader along.

The second, equally obvious departure marked by The Deportees and Other Stories concerns the ethnicity of its primary characters. With two exceptions, every story in the book prominently features characters who are immigrants or expatriates or both—four of them, specifically, from Africa. Doyle writes in his introduction that “one in every ten people living in Ireland wasn’t born here” (xiii), and that this nation-changing influx came on startlingly quickly: “I went to bed in one country and woke up in a different one” (xi). Against this roiling backdrop of change, tension, confrontation, paranoia, and acceptance, of black men and women coming to live and work in one of the oldest, most tradition-bound nations in Europe, Doyle constructs these cunning, twisty tales, playing off the reader’s embedded expectations and stereotypes like a maestro.

In these days of globalization and terrorism, with venomous debates over immigration and identity, The Deportees has explicit relevance. Speaking of contemporary fiction as having a “message” is, of course, considered ridiculously unfashionable and grade schoolish; yet these stories are so unexpected in their turns toward the accidentally humane, so humble and cheering in their humor and small decencies, that one cannot help but feel that the simple act of reading them is somehow bearing witness to the possibility of a saner, freer world. Doyle has a clear eye, and is unafraid. Those are especially valuable traits for a writer, so far, in this still-new century.

ABOUT RODDY DOYLE

Roddy Doyle was born in Dublin in 1958 and attended University College, Dublin, before becoming a teacher in Kilbarrack, North Dublin. He has written eight novels, including Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, which won the Man Booker Prize in 1993. Each of the books in his Barrytown trilogy has been made into a successful film, with Doyle doing the screen adaptations himself. He has also written several stage plays and books for children and young adults. He lives in Dublin, Ireland.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS