Excerpts

Life-Changing Tips from Atomic Habits

Author James Clear provides actionable ways to change our habits – little by little.

James Clear, author of the New York Times bestselling book, Atomic Habits, is one of the world’s leading experts on habit formation. The key to creating habits that stick (and breaking bad ones) is all in the system. In Atomic Habits, Clear teaches readers simple behaviors, drawn from biology, psychology, and neuroscience, that can be easily applied to daily life and work, and make positive behaviors repeatable and bad behaviors repugnant. Read our interview with James Clear to hear his advice in his own words, or start reading an excerpt from Atomic Habits below. And, if you want to get specific advice from James about ways to read more, check out James’ essay on “How to Make Reading a Habit.”

How to Keep Your Habits on Track

A habit tracker is a simple way to measure whether you did a habit. The most basic format is to get a calendar and cross off each day you stick with your routine. For example, if you meditate on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, each of those dates gets an X. As time rolls by, the calendar becomes a record of your habit streak.

Countless people have tracked their habits, but perhaps the most famous was Benjamin Franklin. Beginning at age twenty, Franklin carried a small booklet everywhere he went and used it to track thirteen personal virtues. This list included goals like “Lose no time. Be always employed in something useful” and “Avoid trifling conversation.” At the end of each day, Franklin would open his booklet and record his progress.

Jerry Seinfeld reportedly uses a habit tracker to stick with his streak of writing jokes. In the documentary Comedian, he explains that his goal is simply to “never break the chain” of writing jokes every day. In other words, he is not focused on how good or bad a particular joke is or how inspired he feels. He is simply focused on showing up and adding to his streak.

“Don’t break the chain” is a powerful mantra. Don’t break the chain of sales calls and you’ll build a successful book of business. Don’t break the chain of workouts and you’ll get fit faster than you’d expect. Don’t break the chain of creating every day and you will end up with an impressive portfolio. Habit tracking is powerful because it leverages multiple Laws of Behavior Change. It simultaneously makes a behavior obvious, attractive, and satisfying.

Let’s break down each one.

Benefit #1: Habit tracking is obvious.

Recording your last action creates a trigger that can initiate your next one. Habit tracking naturally builds a series of visual cues like the streak of X’s on your calendar or the list of meals in your food log. When you look at the calendar and see your streak, you’ll be reminded to act again. Research has shown that people who track their progress on goals like losing weight, quitting smoking, and lowering blood pressure are all more likely to improve than those who don’t. One study of more than sixteen hundred people found that those who kept a daily food log lost twice as much weight as those who did not. The mere act of tracking a behavior can spark the urge to change it.

Habit tracking also keeps you honest. Most of us have a distorted view of our own behavior. We think we act better than we do. Measurement offers one way to overcome our blindness to our own behavior and notice what’s really going on each day. One glance at the paper clips in the container and you immediately know how much work you have (or haven’t) been putting in. When the evidence is right in front of you, you’re less likely to lie to yourself.

Benefit #2: Habit tracking is attractive.

The most effective form of motivation is progress. When we get a signal that we are moving forward, we become more motivated to continue down that path. In this way, habit tracking can have an addictive effect on motivation. Each small win feeds your desire.

This can be particularly powerful on a bad day. When you’re feeling down, it’s easy to forget about all the progress you have already made. Habit tracking provides visual proof of your hard work — a subtle reminder of how far you’ve come. Plus, the empty square you see each morning can motivate you to get started because you don’t want to lose your progress by breaking the streak.

Benefit #3: Habit tracking is satisfying.

This is the most crucial benefit of all. Tracking can become its own form of reward. It is satisfying to cross an item off your to‑do list, to complete an entry in your workout log, or to mark an X on the calendar. It feels good to watch your results grow — the size of your investment portfolio, the length of your book manuscript — and if it feels good, then you’re more likely to endure.

Habit tracking also helps keep your eye on the ball: you’re focused on the process rather than the result. You’re not fixated on getting six-pack abs, you’re just trying to keep the streak alive and become the type of person who doesn’t miss workouts.

In summary, habit tracking (1) creates a visual cue that can remind you to act, (2) is inherently motivating because you see the progress you are making and don’t want to lose it, and (3) feels satisfying whenever you record another successful instance of your habit. Furthermore, habit tracking provides visual proof that you are casting votes for the type of person you wish to become, which is a delightful form of immediate and intrinsic gratification.

You may be wondering, if habit tracking is so useful, why have I waited so long to talk about it?

Despite all the benefits, I’ve left this discussion until now for a simple reason: many people resist the idea of tracking and measuring. It can feel like a burden because it forces you into two habits: the habit you’re trying to build and the habit of tracking it. Counting calories sounds like a hassle when you’re already struggling to follow a diet. Writing down every sales call seems tedious when you’ve got work to do. It feels easier to say, “I’ll just eat less.” Or, “I’ll try harder.” Or, “I’ll remember to do it.” People inevitably tell me things like, “I have a decision journal, but I wish I used it more.” Or, “I recorded my workouts for a week, but then quit.” I’ve been there myself. I once made a food log to track my calories. I managed to do it for one meal and then gave up.

Tracking isn’t for everyone, and there is no need to measure your entire life. But nearly anyone can benefit from it in some form — even if it’s only temporary.

What can we do to make tracking easier?

First, whenever possible, measurement should be automated. You’ll probably be surprised by how much you’re already tracking without knowing it. Your credit card statement tracks how often you go out to eat. Your Fitbit registers how many steps you take and how long you sleep. Your calendar records how many new places you travel to each year. Once you know where to get the data, add a note to your calendar to review it each week or each month, which is more practical than tracking it every day.

Second, manual tracking should be limited to your most important habits. It is better to consistently track one habit than to sporadically track ten.

Finally, record each measurement immediately after the habit occurs. The completion of the behavior is the cue to write it down. This approach allows you to combine the habit-stacking method with habit tracking.

The habit stacking + habit tracking formula is:

After [CURRENT HABIT], I will [TRACK MY HABIT].

After I hang up the phone from a sales call, I will move one paper clip over.

After I finish each set at the gym, I will record it in my workout journal.

After I put my plate in the dishwasher, I will write down what I ate.

These tactics can make tracking your habits easier. Even if you aren’t the type of person who enjoys recording your behavior, I think you’ll find a few weeks of measurements to be insightful. It’s always interesting to see how you’ve actually been spending your time.

Creating Identity-Based Habits

Why is it so easy to repeat bad habits and so hard to form good ones? Few things can have a more powerful impact on your life than improving your daily habits. And yet it is likely that this time next year you’ll be doing the same thing rather than something better.

It often feels difficult to keep good habits going for more than a few days, even with sincere effort and the occasional burst of motivation. Habits like exercise, meditation, journaling, and cooking are reasonable for a day or two and then become a hassle.

However, once your habits are established, they seem to stick around forever — especially the unwanted ones. Despite our best intentions, unhealthy habits like eating junk food, watching too much television, procrastinating, and smoking can feel impossible to break.

Changing our habits is challenging for two reasons: (1) we try to change the wrong thing and (2) we try to change our habits in the wrong way. In this chapter, I’ll address the first point. In the chapters that follow, I’ll answer the second.

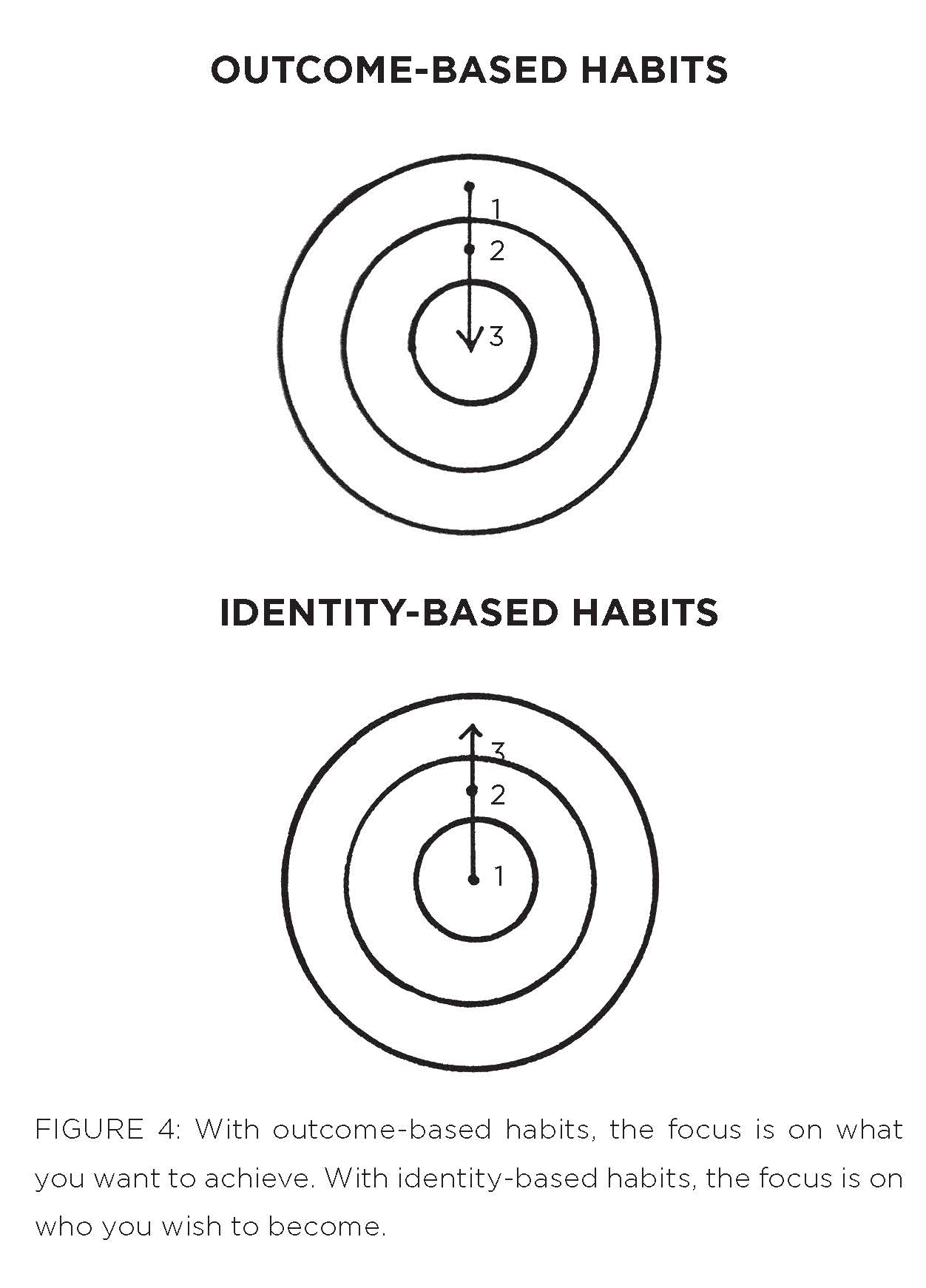

Our first mistake is that we try to change the wrong thing. To understand what I mean, consider that there are three levels at which change can occur. You can imagine them like the layers of an onion.

The first layer is changing your outcomes. This level is concerned with changing your results: losing weight, publishing a book, winning a championship. Most of the goals you set are associated with this level of change.

The second layer is changing your process. This level is concerned with changing your habits and systems: implementing a new routine at the gym, decluttering your desk for better workflow, developing a meditation practice. Most of the habits you build are associated with this level.

The third and deepest layer is changing your identity. This level is concerned with changing your beliefs: your worldview, your self-image, your judgments about yourself and others. Most of the beliefs, assumptions, and biases you hold are associated with this level.

Outcomes are about what you get. Processes are about what you do.

Identity is about what you believe. When it comes to building habits that last — when it comes to building a system of 1 percent improvements — the problem is not that one level is “better” or “worse” than another. All levels of change are useful in their own way. The problem is the direction of change.

Many people begin the process of changing their habits by focusing on what they want to achieve. This leads us to outcome-based habits. The alternative is to build identity-based habits. With this approach, we start by focusing on who we wish to become.

Imagine two people resisting a cigarette. When offered a smoke, the first person says, “No thanks. I’m trying to quit.” It sounds like a reasonable response, but this person still believes they are a smoker who is trying to be something else. They are hoping their behavior will change while carrying around the same beliefs.

The second person declines by saying, “No thanks. I’m not a smoker.” It’s a small difference, but this statement signals a shift in identity. Smoking was part of their former life, not their current one. They no longer identify as someone who smokes.

Most people don’t even consider identity change when they set out to improve. They just think, “I want to be skinny (outcome) and if I stick to this diet, then I’ll be skinny (process).” They set goals and determine the actions they should take to achieve those goals without considering the beliefs that drive their actions. They never shift the way they look at themselves, and they don’t realize that their old identity can sabotage their new plans for change.

Behind every system of actions is a system of beliefs. The system of a democracy is founded on beliefs like freedom, majority rule, and social equality. The system of a dictatorship has a very different set of beliefs like absolute authority and strict obedience. You can imagine many ways to try to get more people to vote in a democracy, but such behavior change would never get off the ground in a dictatorship. That’s not the identity of the system. Voting is a behavior that is impossible under a certain set of beliefs.

A similar pattern exists whether we are discussing individuals, organizations, or societies. There are a set of beliefs and assumptions that shape the system, an identity behind the habits.

Behavior that is incongruent with the self will not last. You may want more money, but if your identity is someone who consumes rather than creates, then you’ll continue to be pulled toward spending rather than earning. You may want better health, but if you continue to prioritize comfort over accomplishment, you’ll be drawn to relaxing rather than training. It’s hard to change your habits if you never change the underlying beliefs that led to your past behavior. You have a new goal and a new plan, but you haven’t changed who you are.

The story of Brian Clark, an entrepreneur from Boulder, Colorado, provides a good example. “For as long as I can remember, I’ve chewed my fingernails,” Clark told me. “It started as a nervous habit when I was young, and then morphed into an undesirable grooming ritual. One day, I resolved to stop chewing my nails until they grew out a bit. Through mindful willpower alone, I managed to do it.”

Then, Clark did something surprising.

“I asked my wife to schedule my first-ever manicure,” he said. “My thought was that if I started paying to maintain my nails, I wouldn’t chew them. And it worked, but not for the monetary reason. What happened was the manicure made my fingers look really nice for the first time. The manicurist even said that — other than the chewing — had really healthy, attractive nails. Suddenly, I was proud of my fingernails. And even though that’s something I had never aspired to, it made all the difference. I’ve never chewed my nails since; not even a single close call. And it’s because I now take pride in properly caring for them.”

The ultimate form of intrinsic motivation is when a habit becomes part of your identity. It’s one thing to say I’m the type of person who wants this. It’s something very different to say I’m the type of person who is this.

The more pride you have in a particular aspect of your identity, the more motivated you will be to maintain the habits associated with it. If you’re proud of how your hair looks, you’ll develop all sorts of habits to care for and maintain it. If you’re proud of the size of your biceps, you’ll make sure you never skip an upper-body workout. If you’re proud of the scarves you knit, you’ll be more likely to spend hours knitting each week. Once your pride gets involved, you’ll fight tooth and nail to maintain your habits.

True behavior change is identity change. You might start a habit because of motivation, but the only reason you’ll stick with one is that it becomes part of your identity. Anyone can convince themselves to visit the gym or eat healthy once or twice, but if you don’t shift the belief behind the behavior, then it is hard to stick with long-term changes. Improvements are only temporary until they become part of who you are.

The goal is not to read a book, the goal is to become a reader.

The goal is not to run a marathon, the goal is to become a runner.

The goal is not to learn an instrument, the goal is to become a musician.

Your behaviors are usually a reflection of your identity. What you do is an indication of the type of person you believe that you are — either consciously or nonconsciously. Research has shown that once a person believes in a particular aspect of their identity, they are more likely to act in alignment with that belief. For example, people who identified as “being a voter” were more likely to vote than those who simply claimed “voting” was an action they wanted to perform. Similarly, the person who incorporates exercise into their identity doesn’t have to convince themselves to train. Doing the right thing is easy. After all, when your behavior and your identity are fully aligned, you are no longer pursuing behavior change. You are simply acting like the type of person you already believe yourself to be.

Excerpted from Atomic Habits by James Clear. Copyright © 2018 by Avery. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.