How well do we know our parents? What do we know of their lives before we arrived? Just as running into your elementary school teacher in real life was a strange moment for many of us as kids – somehow, we only thought about teachers existing in that classroom space with us – so, too, can the realization be that our parents exist(ed) outside their parent space. Even as adults, it can be awkward to relate to parents from an adult-to-adult position, and it’s common for parents and children to not tell each other the types of stories that they confide in their friends.

Anya Yurchyshyn admits that like most kids, until she was in her late teens, she assumed that she was the center of her parents’ universe. She knows that it wasn’t true, but lacked the awareness as a child to know that parents have lots of other things going on. When her father died in a car accident in his native Ukraine after journeying there to help with the country’s re-building in the early Nineties, Anya was 14. In many ways, her father had been cruel to Anya prior to his leaving, and his death felt like a liberation from the pain he had caused her.

Her relationship with her mother was equally fraught, and her mother’s alcoholism meant that Anya switched roles, becoming her mother’s caretaker. When her mother died, Anya again felt a sense of relief. But she also worried that something might be wrong with her: grief books told her that she was supposed to be feeling certain emotions that she didn’t feel, and she began keeping a blog in which she wrote anonymously about this tangle of emotions that she felt.

While going through her mother’s things, Anya discovered a series of love letters and other documents that made it clear to her that she had known little about her parents’ lives, of who they had been as children, teenagers, and the adults to whom she was born. Anya had grown up with one older sister. She had discovered as a child that before she was born, her older brother had died. As she sorted her way through documents as an adult, she also learned the tragic details of his death, and began to piece together a story that helped her understand why her upbringing had been so painful.

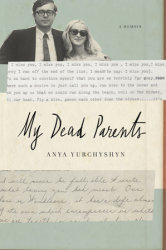

In writing My Dead Parents, Anya Yurchyshyn made the difficult decision to tell the lost stories of her mother and father. Difficult not only because she found out so much about them, but also because she insisted that in writing the book, she had to be honest about herself as a teenager, a period of time when a lot of us are struggling for autonomy and against parental control.

In an interview, Anya talked to Penguin Random House about the writer’s temptation in memoir to not be honest about who we were in the past; the discovery through writing that we are not alone; and how what she has learned about her parents’ lives has changed her feelings toward them even as she recognizes that there are still parts of her parents’ lives that she will never be able to know about.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: I’d like to start with a question of craft. I know that your previous work had been in short stories and fiction, and I am wondering if you ever felt the temptation to turn this into a novel rather than a memoir.

ANYA YURCHYSHYN: I was not tempted, and that could have been for a couple of reasons. One is that my fiction has never been autobiographical. I prefer to just make things up. I was so interested in finding the truth. After I had all of the information, I think that fictionalizing it would have been disrespecting the story and the work I was trying to do.

There were certainly times when I was working on the book that I was tempted to skip things, though. Sometimes, I worried that things were boring – I was tempted to completely skip my adolescence (laughs). I would shudder and think, “Really? Did I say that?”

And in those moments I would think that it would be great as a novel, because I could make a particular thing more interesting or pretend it didn’t happen, but as hard as it was to be constrained by the truth, it was also helpful in that I had a task that was overwhelming enough.

I hope that because it is a true story, that will lend to its impact. Certainly you can identify with characters in fiction, but I think when you’re telling a personal story, the reader has the comfort of reading about something that a real person went through. Reading someone else’s experience offers insight into your own.

PRH:I want to clarify that the reason I asked that question is not because I think fiction is disguised autobiography, but rather, when we are writing memoir, especially when dealing with difficult material, the temptation is there to put a layer between ourselves and it. So, I guess I’m asking whether you ever felt the temptation to distance yourself from the story you were telling?

AY: Every day.

I worked on this book for three years. I wanted distance from it.

It was absolutely difficult, especially as I uncovered things that had happened. And for a long time, I tried to ignore that. I tried to just treat it as a job.

But I had gone out in search for information and I knew it wouldn’t all be positive, and so that was its own emotionally and mentally exhausting experience. But you have to get up the next day and you have to go. It’s the basic function of being a diligent writer: writing and re-writing.

But for me it was also the discovery of things that pained me. I found myself navigating my own grief and grief that I perceived them to have, that hadn’t been shared with me.

PRH:What motivated you to take on this project about your parents’ lives?

AY: There were two phases to the project. There was the blog that I started anonymously – a decision that felt right. I had conflicting impulses, because I did feel ready to be rid of my parents. But as documents emerged that detailed what had happened in their lives, I realized my knowledge of them was extremely limited. My blog was this messy mixture of explanations for why I felt the way that I did about my parents, and then it was a place to say that I didn’t feel that I had an ordinary or expected grief experience, and I was feeling defensive about that.

I want to be able to say these things that I know other people can relate to, but what I really felt when I was looking at other grief books or grief memoirs is that I just couldn’t relate. I wrote over 50,000 words on the blog. My concern for the book was that I knew why I was interested in this topic, but why would anyone else be interested?

When I came out (under my real name) in the article that I wrote for BuzzFeed, I got a really strong response. It gave me confidence, but it confirmed what I hoped had been true, that this was something that other people could relate to. I think it’s universal: it’s hard for children to know their parents, even when they become adults, because the dynamics of the relationship often stay in place. I think it must be hard for parents to make those decisions about what they want to tell their kids.

There were so many times that people expected me to be sad about my parents’ deaths, and I was very aware that I was disappointing them at not having that reaction. Because I am self-critical, I went back and forth between wanting to be proud of my reaction to thinking that there was something wrong with me. Family relationships and grief are really, really complicated. It was great for me to be able to explore that and to hear from some people who had felt similarly.

I hadn’t started it as a means for connecting. Even if no one had read it, I still would have done it because it was interesting and good work for me to be doing. But it helped me to have more confidence to go forward.

PRH:I think the book also serves on a commentary about the fact that we have developed these expectations about how we are supposed to perform our grief. For me, my dad’s death wound up devastating me more than I expected it to, and even a year later, I was still struggling with it. I found myself saying,”This is a personal experience and I’m sorry I’m not meeting your expectations for how I’m supposed to be doing this.”

You must have had mixed feelings about your mother’s death, wondering if it was an end to her suffering.

AY: My biggest fear was that her health aide would find her at the bottom of stairs and that she would spend the last 20 years of her life with a traumatic brain injury from falling. It was very hard for me to accept that she wasn’t going to get better. And some part of me never really let go of hoping that, “If I just say the right thing this time,” I can undo all the damage that alcohol has done to her.

It would have felt selfish, wishing that she was still alive. Her life was really awful at that point. She was really sad. But I think one of the things that kept her drinking was the shame and the sadness that she had drunk so much already. She was deeply aware of how limited her world became. It really was a room and a bathroom. It didn’t seem as if she was living for anything. She certainly didn’t seem to get any joy from life.

I would, of course, have kept her in my life no matter what but it would have been hard to go through another 15 years of that. She died of heart failure because of the alcoholism. I think she was done.

PRH:There were so many different poignant moments in the book, but one of the most poignant for me was when you realized that your father had instilled in you a mistrust of your own abilities, this expectation of failure.

When you were looking at his teenaged life, he had been one of those teenagers for whom all things had seemed possible, and now that you know all of the things that your parents experienced before you were born, do you feel that you my now understand why your father raised you with such low expectations? It’s painful to think about, but do you have an understanding of where that came from?

AY: I think that most people as parents are doing what they think is best, even if what they’re doing is terrible. I’m sure that it didn’t occur to my father that things he said to me when I was six, eight, ten would stay with me, and that I would internalize his voice. I think that if he had understood that, it’s possible that it would have changed his behavior.

One thing about his childhood that gave me some insight was that his childhood was rough – living in the war (World War II), living in different countries, and then really thriving despite that. He really valued academics and I think it was frustrating to him that I had these learning difficulties. I think he wished “Anya would get it together.” Some part of him must have thought that I was making a choice. Maybe he would reflect on his own childhood and think that I couldn’t really have a better life, so what was going on? And to me,those wounds are still there. I catch myself minimizing my accomplishments or doubting myself all the time. And again, I think that he was not thinking that far ahead.

He knew I was scared of him. I hated doing homework with him, and there were points when I was writing the book, when I thought, “He saw that it wasn’t working. It did not work, so why did something not go off in his head to try another approach?” He could have sent me to a learning specialist. Was it not worth it? My father was a hyper-focused and a hyper-determined person and it’s possible that he thought that he could get through to me. I was very respectful of my parents at a young age, but it still must not have been similar to the childhood he grew up with. He had pressure that came from him being an immigrant and his mom telling him that “we’re representing Ukrainians.” That’s a lot of pressure to have on himself. I liked school, but I liked it less when it became obvious to me that I wasn’t “good at it,” and I think with his kind of personality, that might have really motivated him where for me, I just wanted to ignore it.

Then when I found out about my brother when I was ten years old, I had never met him and it was something that was never talked about. My father was tough on my sister, but he was tougher on me. I had more problems, but I think both of my parents were expressing grief that came with a lot of anger. Medical professionals not being able to save him. My father did not talk about losing his son at all. I think that it’s very possible that the way he dealt with me was an unintentional way of expressing his grief.

PRH:Did you find yourself looking for explanations that would excuse their behavior?

Or were you looking for a way to understand your parents’ behavior that didn’t come from their meanness but maybe compassion?

AY: Definitely. Because an explanation would be comforting. He was very hard on me, and there was this inability on his part to see that something wasn’t working. I think I’m as close as I can get to an explanation, yet even with all the research there are still questions that can’t be answered. But even if they had been alive, there would still be questions because I know this about myself: People are not great self-reporters. They might not accurately represent something. Not even on purpose, but because their memories work on their perspectives.

My dad died when I was a teenager, and I think I needed that distance in order to broaden my perspective about their lives. When I was younger, I needed my perspective to be true to me because it didn’t take my experiences away. And that was important for me.

That was something that I was trying to battle in the book. I was worried that the first chapters about my childhood are depressing because I wasn’t a happy kid. I was worried that readers wouldn’t stick around for my emotional arc. All kids, I am sure, have a running list of things that their parents did wrong. My friends with kids are talking about it. I know that they’re struggling.

Even for teenagers, it’s difficult to understand that your parents are trying their best. I’m pretty confident that most of them are and that mistakes that they make are honest. Being honest about the human condition of trying hard and asking how do you raise another human? Teenagers are so interested in pushing boundaries and breaking rules that they see their parents as an impediment. They don’t get how hard the job is that parents are doing.

I was a very rebellious, angry teenager and I only thought about myself. That must have been really annoying for my mom. And I spoke to my mother’s friends and they agreed that there were moments when I was awful. Because of course she would bitch to her friends about me as she is entitled to do. In some ways, I felt entitled to have that experience. I never thought about what her perspective of that time might have been, how much she might have been worrying.

I was so happy that my father was gone, and I thought she was supposed to be happy, too. Which makes no sense. They hadn’t gotten along, but that was her husband, still. He left her for Ukraine. Back in that time, it wasn’t like she could pick up the phone and call him. It must have been terrible and lonely for her. And then you’re stuck with a super bratty kid.

Even though I know that teenagers do what they do, I feel guilty for everything that hurt her, and not understanding that it was great for me that my father was gone but it felt terrible for her.

PRH:In the middle of the book, you talk about what happened to your mother when she was a girl. You talk about wanting to go back and protect her as a girl. I’m wondering if you think that this writing project may have been a way for you to do that in a symbolic way. Did the writing make you feel in any way that you were changing the things that happened?

AY: I didn’t think it was changing the way things happened. The things that involved me so often, but I wished that I could have, which is something I talk about in the book. I was so angry and so sad when I realized what had happened to my mom. I assume that those events were a factor in who she became. I felt the same way when I was working on issues around my brother’s death. Like I know how this ends. And I wish I could stop it. From my perspective, I know things that they didn’t. That is a burden of information. I was constantly frustrated that I couldn’t change parts of their lives but I do feel that ultimately the work that I did changed my relationship to them. And in some ways that’s harder for me because it’s much easier to think, “I didn’t like these people. They were complicated and caused me a lot of grief or problems and lucky me. They’re out of my life.”

But actually developing compassion for them and discovering all the pain that they lived with taught me to have so much compassion for them as humans.

It’s not a child’s responsibility to feel compassion for your parents when you’re little. Becoming close to their pain caused me so much pain and that didn’t happen before the book.

What I’m left with is a lot more complicated. Because it takes time to write a book, by the time I was writing about certain things, I had a hard time writing about it because I don’t really feel that way anymore. But that was how I felt then. Even though that will turn people off, it’s kind of the point that you felt that way.

When I understood the work my father was doing, I was embarrassed. It feels better to say, “Your exiting my life was really great for me but I’m so sorry that those things happened to you. You were actually living out this lifelong dream. I had no idea.”

It was really important that I was writing so honestly about my parents and that I be as honest about myself and treat myself in the same way.