Books by B. Smith

Author Q&A

Five years ago, Dan Gasby and his famous wife, B. Smith, led a very different life than they do today. B. Smith was a national lifestyle brand, the African-American Martha Stewart: author of three best-selling entertaining books, co-owner with Dan of three B. Smith restaurants (Manhattan, Sag Harbor, and Washington, DC), and host of a nationally syndicated television show. Their sprawling apartment with wraparound terrace overlooked Central Park; their compound in Sag Harbor surveyed the bay. Then, for B. at sixty-two, came troubling warning signs – signs of what would be diagnosed as early-onset Alzheimer’s.

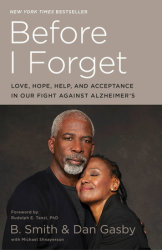

As public figures, Dan and B. made a decision to fight Alzheimer’s in a public way: to speak candidly, and from the heart, about how it was changing their lives. By the time B. was diagnosed, they had learned that African Americans were twice as likely to get the disease as white people, and that women were more likely to get it than men. That made B. Smith a very special spokesperson – and led to the book that Harmony has just published: Before I Forget: Love, Hope, Help and Acceptance in our Fight Against Alzheimer’s, by Dan and B., with veteran Vanity Fair contributing editor Michael Shnayerson. To Join B. and Dan’s fight against Alzheimer’s, visit BSmith.com.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: What were those first warning signs, and how did you and B. deal with them?

DAN GASBY: It was like that movie “Groundhog Day.” B. would repeat herself, telling me a story she’d just told me an hour before. I thought it was just fatigue. She’d leave the teapot on the stove. Once she put my wallet on the roof of our car and drove off; I didn’t see that wallet again. There’d be non sequiturs; things that just didn’t make sense. I’d get frustrated, and B. would get mad. An hour later, she’d be totally different: friendly, even flirtatious, until another spell of anger came out of nowhere.

PRH: Did you think Alzheimer’s?

DG: Not at all. At first I thought our marriage was teetering; maybe it had run out of gas. For a year or more, B.’s outbursts would leave me seething; I’d find solace behind the bar of our restaurant on Theater Row, talking with the patrons and drinking my problems away. Then came a turning point: B. was on “The Today Show,” demonstrating a Labor Day recipe. Suddenly she froze, unable to finish her sentence. That silence lasted nine or ten seconds – an eternity on live TV. That was when I knew we had a serious problem.

PRH: So you went to an Alzheimer’s doctor?

DG: Not right away. I still couldn’t bring myself to think B. might have Alzheimer’s. So first we went to a doctor whose diagnosis was depression. He put patches on her back that delivered anti-depression medicines. All they did was freak her out. So on we went to a neurologist associated with Mt. Sinai hospital in upper Manhattan who had B. take simple tests: like drawing a clock and showing the hands at three PM. I was surprised: She couldn’t do it. I think maybe I’d been in denial. We had digital clocks around the house and in the car.

PRH: In the book, you describe that moment of getting the actual diagnosis of Alzheimer’s – it’s sort of everyone’s nightmare.

DG: Yes. We were in the very cramped office of Dr. Martin Goldstein, a distinguished Alzheimer’s doctor at Mt. Sinai. It was so cramped that my knees were jammed against the front of his desk. He showed us a lateral scan of B.’s brain. It was gray, except for these small, white blotches that looked like Wite-Out. They were amyloid plaques, and where they were, B.’s brain cells were fighting a losing battle. We were both stunned. B.’s shock wore off faster than mine, though: She just forgot. I just kept thinking our lives had changed, right there, forever.

PRH: From the first, you and B. agreed to take your story public. Some have criticized you for putting B. out there. How do you respond to that?

DG: She wants to be there! I mean – look, I know what the argument is, that B. wasn’t of sound mind to make a decision like this. But B. has always given of herself, whether it was being a candy striper when she was a girl to working with children at risk, or doing fundraisers for former prostitutes. She’s always tried to make other people’s lives betters. That’s who she is. She’s still that way, even as her Alzheimer’s has gone from the first of seven stages to the fourth or fifth. She loves connecting with people. If anything, the appearances we’ve made over the last year – starting well before the book’s publication – have kept her brain more vital than it would have been.

PRH: By the time B. got her diagnosis, you were her full-time caregiver.

DG: Absolutely: 86,400 seconds a day, 24/7, 365.

PRH: You write bluntly of the toll that took on you – of the toll it takes on any Alzheimer’s caregiver. Frankly, you had the money to bring in help. Why didn’t you?

DG: In the restaurant business, which is what we were in every day of the year, you’re always surrounded by people. Your one place of privacy is your home. For me, home meant not having to talk to anyone beside my wife and daughter. I didn’t want to give that up and have a stranger in the house. And nor did B., by the way.

PRH: What does “caregiving” really mean on a day to day basis for you with B.?

DG: It’s not just helping her dress and making her meals. She’ll get up in the night and wander down the beach with Bishop, our Italian mastiff. I have to be sure I don’t sleep through that – she might wander off, as she did that terrible night in November 2014.

PRH: That’s a shocking chapter – B. wandering lost up and down Manhattan on a cold night in high heels, until the next day when a friend spotted her sitting disheveled in a coffee shop. Did that force a change in your caregiving?

DG: Yes. We do have a woman who comes in to help as many days as we need her now. But as you noted, we can afford this, and that’s a crucial point. Most of the families of the 5.2 million Americans dealing with Alzheimer’s can’t afford the home care they need. Especially African Americans.

PRH: Your book has a message that seems both urgent and new: not only that many African Americans lack the financial resources to deal with Alzheimer’s – but that they’re more likely to get the disease. Why is that?

DG: It’s almost certainly a genetic reason, but no one knows yet what it is, exactly. There are, of course, no drugs yet that change the course of Alzheimer’s, let alone cure it. So far, this is a disease that no one survives. But there will be drugs – in the foreword to our book, Dr. Rudy Tanzi, one of the leaders in the field, makes that very clear. The problem is that that drug, when it comes, may not work for African Americans.

PRH: Why not?

DG: It just stands to reason that if the genetics of Alzheimer’s are different for African Americans than whites, so may be the way a gene-based new drug works. We’d know for sure – and tailor the drug accordingly – if we had African Americans in new drug trials. Unfortunately, almost none have signed up.

PRH: Again, why?

DG: One word: Tuskegee. That terrible chapter of American medicine, in which poor southern African Americans with syphilis were denied new, life-saving drugs – over decades – so that doctors could analyze their demise is a horror story that still haunts us. If the visibility we’re getting for this book accomplishes nothing else, we want to get the word out there that African Americans must get beyond those fears – new medical ethics laws will never let a Tuskegee happen again – and sign up for those trials. Chances are that you can find one near you, just by going to the national Alzheimer’s Association or my new favorite, BrainHealthRegistry.org.

PRH: From the overflow crowds that have come to hear you and B., it looks like Before I Forget is also reaching people on an emotional level, putting them in touch with people – you and B. – who are going through the same grueling and often lonely gauntlet.

DG: I think it is. Along with telling our story, we’ve got sections at the end of each chapter on how to cope with the disease, from recognizing first symptoms to dealing with end-stage patients. But what people respond to most is our story, and the fact that for all we’ve been through, as hard a journey as this is, I still love B. and she still loves me. Love gets you through, man. In the end, it may be the only thing that does.

Visit other sites in the Penguin Random House Network