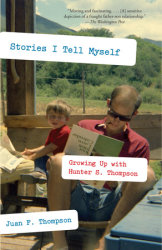

Hunter S. Thompson was an alcoholic, drug addict, and hell-raiser. Certainly that’s the public image of him, and one his son, Juan Thompson, doesn’t dispute in his new memoir about his father, Stories I Tell Myself: Growing Up with Hunter S. Thompson. But his dad was also “a brilliant writer and craftsman of the language,” Thompson writes, “facts that are still overshadowed by his Wild Man persona.” To correct this imbalance, he says, he wrote a book that portrays his dad both truthfully and lovingly.

Previous depictions of the larger-than-life Thompson, such as the films “Where the Buffalo Roam” and “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” show the writer tearing about with a cigarette hanging from his mouth, a bottle at the ready, and nary a concern for the well-being of himself or anyone else in the room. The truth, as his son reveals, was often less entertaining and more frightening, especially for a young boy at the mercy of his parents’ raging battles. To say Thompson was a less-than-model parent would be an understatement. Yet as an adult, his son managed to form a deep and authentic connection to his dad, and the two shared a rewarding, if unconventional, father son relationship up until the day Thompson took his own life in 2005.

Thompson talked to Penguin Random House about his writing process and what it was like growing up the son of a Wild Man.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: What inspired you to write this book now?

JUAN THOMPSON: I first decided to write this book several months after my father’s death in 2005. I felt very strongly that I had to set the record straight about who Hunter was. For many years the focus had always been on his drug use, his drinking, and his crazy behavior, which overshadowed his writing, his idealism, and his complexity as a man. I figured I had sufficient writing skills and talent to come up with a readable book, I had a unique perspective, and I had a story I very much wanted to tell.

PRH: What was the most difficult aspect of the writing process?

JT: Sharon Olds (one of my favorite poets) said in an interview about her book of poems, Stag’s Leap, (about her divorce from her husband):

‘Composition is itself a form of healing. “I focus so hard on the line, like a gladiator in the arena with the lions, just trying to be accurate, not being gloomy about your condition, but making something which may prove to be good.”

What I take from this is that the most important thing is to try to communicate as clearly and accurately as possible to a reader what happened. Doing that forces the writer to try to see and feel to the essence of the thing in order to communicate it to someone else. That was true for me, though I never thought of it that way.

At first I just wanted to celebrate him, but then it gradually became clear to me that that if I was going to tell a real story, I had to include the ugly parts also, and to accept that I was still angry at him for things he had said and done decades earlier. So began a long process of deciding what to include and what to leave out without regard to whether a memory made Hunter look good.

There was also the problem of trying to see the whole arc of the book in my head, how all the stories fit together into a whole to tell a coherent story that would hold a reader’s attention. Meanwhile, I was working my day job, and between that and being a father and husband, I had very little time. Finally, I just didn’t want to work on it. It was hard and frustrating and painful, and there were difficult decisions to make.

The bottom line is that the hardest part of writing the book was trying to write a good book.

PRH: Do you think you would have written a memoir about HST if you weren’t a father yourself?

JT: Yes, absolutely, but it would have lacked an important dimension of my being able to identify to some degree with Hunter as a father.

PRH: What is the greatest misconception about HST you hope to correct with this book?

JT: I would very much like for people to think of Hunter as a writer first, then as a man trying to be a good father and friend, and only then as the drug-crazed Wild Man. He certainly liked drugs, and he liked getting crazy now and then, but that was a side-show. He wasn’t a great writer because he drank too much and did a variety of drugs, he was a great writer in spite of those things. It’s very important to me that people understand this.

PRH: Are there any other memoirs by the children of larger-than-life cultural figures you used as models? Or memoirs you admire in general that you read during the writing process?

JT: I didn’t read a lot of memoirs before starting my book, but I did read a few. The one that really stuck with me was The Tender Bar by J.R. Moehringer. Great book. I still think of it. I highly recommend it. I didn’t study it, but I often thought of it while writing my book. What struck me most was his honesty about himself, and the lack of victimhood. Also, it was just a tight, very well-written book. If any memoir influenced me, it would be that one.

PRH: In what ways did your father’s career teach you how to be a writer, and in what ways did it teach you what NOT to do?

JT: The primary thing I learned from him about being a writer was that it was a very hard way to make a living, and that writing is just hard. Being a writer was the most important thing to Hunter, but it was never easy for him. My agent told me back when I started this book, ‘Don’t quit your day job,’ but she didn’t have to say that. I had no intention of making a run at making a living at writing. Good thing too, since it took me nine years to write it.

PRH: Many of your early memories of your father involve guns, and, as you write in your book, you cleaned the gun he used to shoot himself.

What do you think HST would think about the current debate about guns in the culture and President Obama’s recent executive actions to curb gun violence?

JT: Hunter loved guns, but he was not an absolutist. I think he would reject this recent development of 2nd amendment fundamentalism, this idea that the right to carry any gun anywhere is a sacred human right, equivalent with freedom of speech. This is absurd, it has no constitutional basis, and no rational basis. We didn’t talk about this, but I’m sure Hunter would readily acknowledge that some people should not have guns, and would have not agreed with the idea that people will be safer if they carry a gun in public. Hunter could have gotten a concealed carry permit, but he did not. He didn’t need one. And he never openly carried a gun off his property. Again, there was no reason to, and many reasons not to. Having a gun would make any altercation or confrontation much worse. I don’t think he would have had any problem with Obama’s attempt to strengthen gun control laws, and they are mild changes at best.

I do want to make it clear that I cleaned the gun he used, but I had no idea at the time that he was planning to kill himself, or that he would use that gun. He did, though. I’m not sure how I feel about him asking me to clean it that weekend. Perhaps it was meaningful to him, but had I known, I would not have touched that gun.

PRH: If you could recommend one piece of your father’s writing to a person who had never read him before, what would it be and why?

JT: The best place to start for an HST newbie is The Great Shark Hunt, because it shows the range of Hunter’s writing styles, and his development from a pretty traditional form of journalism to his own unique voice and style. It includes some early articles, excerpts from his three masterpieces, Hell’s Angels, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72, as well as some of his best magazine writing.

PRH: You write, “to his credit, Hunter never encouraged me to be a writer.” What do you think he would think of your memoir?

JT: I never claim to know what Hunter would think or do, that is a losing game, but I would like to think that he would be very proud that I completed it, that it is not badly written, and most important, that I was honest about him. The one thing I do know is that he would be very happy that the book reaffirms what he knew when he killed himself, that I loved him and had forgiven him, and that I knew he loved me.

PRH: You open your book with a poem titled “Forgiving Our Fathers.” Was it necessary for you to forgive HST before writing this book, or did you find a new level of forgiveness and understanding in telling the story of your life with him?

JT: I’m glad someone brought up that poem. I think it’s a beautiful poem, and a few times I have thought, ‘why did I bother writing a book when Dick Lourie already said what there is to say?’

Yes, I had already forgiven him before he died. That was a key to my being able to come closer to him. Therefore, writing the book didn’t help me to forgive him. What it did help me to do was to work through my grief more completely, to write more and more honestly about him and me, to be able to see him more clearly, and to worry less about what people might think of him.

It also helped me to take him into myself, by which I mean that I no longer feel that I have to be surrounded by his possessions to feel that I’m connected to him. He is in me, I don’t need his things. That has been a great gift.