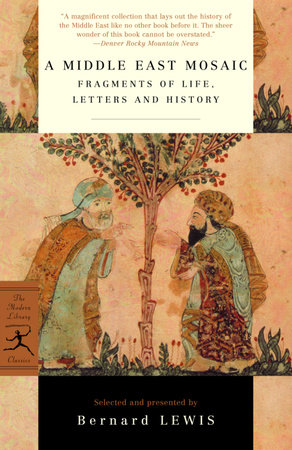

Author Q&A

A conversation with BERNARD LEWIS, author of A MIDDLE EAST MOSAIC — on Assad, the clash of civilizations, technology and modernization, and the lure of the Koran

Q: You were stationed in Syria and Egypt during the Second World War and in your book, in the chapter on war, you give us scenes of WW2 from the point of view of Count Ciano, Mussolini’s brother in law, Churchill and de Gaulle, but also of Sadat. What did the war look like from the point of view of the middle east?

A: I did a brief tour of duty in the Middle East during the war, which took me to Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq. But most of the time I was stationed in London, dealing with Middle Eastern matters. Viewed from inside or outside, the Middle East was crucially important. At the meeting point of Europe, Asia and Africa, bounded by the Soviet Union, German-occupied eastern Europe, and the British Empire, owing allegiance to none of these three, wooed intensively by all of them. Though resented at the time – with some justification – as foreign imperialists, I think the Western allies may claim to have rendered some service to the peoples of the Middle East, since without us they would almost certainly have undergone either Nazi or Soviet occupation. Either would have been bad; still worse would have been a struggle between the two over the Middle East.

Q: When did you first go to the Middle East, and what made you decide to study the region?

A: I first set foot in the Middle East in the autumn of 1937, and spent about seven months there. I was a graduate student at the time, and the purpose of my visit was to acquaint myself with a region that I knew only through books, to improve my knowledge of its languages, and to collect material for my doctoral dissertation. My interest in the region goes back much further. I think I can date it from the beginning of my thirteenth year, when my parents hired a teacher to prepare me for my bar mitzvah. This involved acquiring a sufficient knowledge of Hebrew to read the required short text (without necessarily understanding it) and recite it in the bar mitzvah service. At that time, that was about all that was expected. But I had always been fascinated by languages and history, which were my best subjects at school. Here was a new language – Hebrew – to add to the French and Latin I was doing at school, and moreover one which possessed some of the qualities of both, being both classical and modern at the same time. To everyone’s astonishment, I told my teacher that I actually wanted to learn this language, as distinct from merely reciting it. Fortunately, I had a teacher who could respond to my youthful enthusiasm. He instructed me in the language, and at my urgent request, continued to teach me after the ceremonies were completed. From Hebrew I went on to study some of the cognate languages, first Aramaic, and then Arabic. This last opened an entirely new world, and going to university a few years later gave me the opportunity to explore it.

I had opted to take an honors degree in history and honors students were asked to choose one regional specialization, in addition to the standard West European history. I chose the Middle East, and this allowed – indeed required – me to continue my study of Arabic. Later, as a graduate student, I added Persian and Turkish.

Q: One of the themes that runs through your book is the deep suspicion east and west have had of each other’s customs and ways, ever since the crusades. But you also show us many instances of curiosity and fascination, and of cross-cultural pollination. When did middle eastern rulers first enter into relations with the west? What did they think of us?

A: The most important factor in the relationship – and also in the conflicts – between the Middle East and the West has been their resemblances, far more than their differences. Both shared the heritage of antiquity: Roman law and government, Greek science and philosophy, Hebrew religion and scripture, and the more ancient civilizations of the Mediterranean lands and the Middle East. Both were religiously defined civilizations, the one Christian, the other Muslim. Both claimed to be the custodians of God’s final revelation, with a duty to bring it to all mankind. Two such religions, two such civilizations, sharing a heritage, a mission, and the same environment, were bound to clash. But even at the worst moments of hostility, they were able to understand each other, to establish a level of communication which would have been impossible for either of them to achieve with the more remote civilizations of the East, in India and China. This facilitated meaningful argument – when a Christian or a Muslim said to each other "you are an infidel and you will burn in hell," each understood exactly what the other meant, because both meant the same thing. Such a remark would have been unintelligible to a Buddhist or a Confucian. This resemblance made for suspicion, rivalry and hostility in the past and still does so to a considerable extent at the present time. One can only hope that it may also provide a basis for better mutual understanding. In this book I have tried to give examples of how Europeans and Middle Easterners, at different periods in their history, saw each other, displaying remarkable similarities, on the one hand in their arrogance and ignorance, on the other in their aspirations.

Q: It has become popular in recent years to denounce America (and Europe) for objectifying and stereotyping the east. You seem in this book to be challenging some of the assumptions behind these attacks. What did you hope to show us about the relations between the two cultures?

A: "Objectifying and stereotyping the Other" is a common failing of human

societies, from the most primitive tribe to the most sophisticated civilization. There is no lack of such stereotypes in Western writing about the Middle East and also – though this is often overlooked – in Middle Eastern writing about the West. But we should not objectify and stereotype the literature of either side about the other. There were also visitors who made an honest attempt to understand an alien culture, and explain it to their compatriots. Some went so far as to learn the languages and to translate some of their writings. This kind of intellectual curiosity aroused suspicion in those who did not share it. I have tried to present a representative selection of these various perceptions. Much has been written of how the West perceived and presented the Middle East. I thought it might be useful to match this with some examples of how the Middle East saw – and sees – the West.

Q: You and Edward Said famously locked horns at the time of the publication of his book Orientalism, a scathing attack on western portrayals of the east. Is this book an answer to Said?

A: This book is in no sense intended as an answer to anybody. Its purpose is not polemical, but explanatory – to show how different civilizations, at different stages of their evolution, perceived each other and themselves. As I said, my purpose is not polemical, but if the reader comes away with a realization that ignorance and arrogance are not the monopoly of anybody, the book will have achieved some of its purpose.