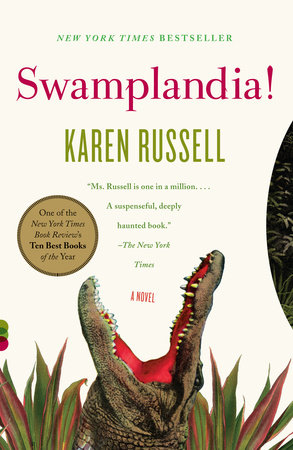

Swamplandia!

By Karen Russell

By Karen Russell

By Karen Russell

By Karen Russell

By Karen Russell

Read by Arielle Sitrick and David Ackroyd

By Karen Russell

Read by Arielle Sitrick and David Ackroyd

Part of Vintage Contemporaries

Category: Literary Fiction | Women's Fiction

Category: Literary Fiction | Women's Fiction

Category: Literary Fiction | Women's Fiction | Audiobooks

-

$18.00

Jul 26, 2011 | ISBN 9780307276681

-

Feb 01, 2011 | ISBN 9780307595447

-

Feb 01, 2011 | ISBN 9780307748881

788 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

The Watchers

Medusa’s Ankles

A Friend of the Earth

The Water Cure

Revelator

Early Riser

The House of Whispers

The Blue Girl

The Red House

Praise

A New York Times Best Book of the Year

One of Granta’s Best Young American Novelists

Selected for the New Yorker’s 20 Under 40

Nominated for the Orange Prize

“Absolutely irresistible. . . . A suspenseful, deeply haunted book. . . . A marvel.” —The New York Times

“[Russell] has thrown the whole circus of her heart onto the page, safety nets be damned. . . . Russell has deep and true talent.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Vividly worded, exuberant in characterization, the novel is a wild ride. . . . This family, wrestling with their desires and demons . . . will lodge in the memories of anyone lucky enough to read Swamplandia!” —The New York Times Book Review

“The bewitching Swamplandia! is a tremendous achievement.” —Entertainment Weekly

“Seduces before you’ve turned the first page.” —People

“If no such thing as the Great Floridian Novel already existed, consider it done. . . . A novel of idiosyncratic and eloquent language; hyperreal, Technicolor settings; and larger-than-life characters who are nonetheless heartbreakingly vulnerable and keenly emotional. It’s a tour de force.” —Elle

“Beautiful, dark, and funny.” —Rolling Stone

“A spook-house masterpiece.” —Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Dazzlingly original. . . . Like the state itself, Swamplandia! is a crossroads where the wild and the tame, the spectacular and the mundane meet; underneath the hubbub of the fantastic lies a family of misfits at sea in their grief—theirs is a story that is as ordinary as it is heartbreaking.” —Boston Globe

“Wonderfully imaginative.” —The Seattle Times

“A rich and humid world of spirits and dreams, buzzing mosquitoes and prehistoric reptiles, baby-green cocoplums and marsh rabbits, and musty old tomes about heroes and spells. With Ava [Russell] has created a goofy and self-conscious girl who is young enough to hope that all darkness has an answering lightness.” —The Economist

“A lusciously written phantasmagorical treat.” —Palm Beach Post

“Swamplandia! flashes brilliantly—holographically—between a surreal tale brimming with sophisticated whimsy and an all-too-realistic portrait of a quaint but dysfunctional family under pressure in a world that threatens to make them obsolete. . . . Ava is a true contemporary heroine and not easily forgotten.” —More

“Winningly told.” —Vogue

“Audacious, beguiling. . . . Ava’s story turns into a tale that could have been concocted by Flannery O’Connor in partnership with the Brothers Grimm—in other words, a first-class nightmare. . . . You will admire this novel for its prose, but you will love it for its big heart.” —The Daily Beast

“Ava’s juicy, poetic voice, assembled through sheer willpower and joie de vivre and desperation from a self-taught young genius’s love of language, is what carries this book. . . . [A] garish and fierce beauty.” —Salon

“The talent Karen Russell paraded in her remarkable short story collection St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves has turned into mastery.” —Chicago Sun-Times

“Swamplandia! is both a celebration of the Everglades and an elegy for it. . . . Russell has created a credible, captivating universe.” —The Sun Sentinel

“Think Scout Finch if she’d been raised in an old-school tourist attraction instead of a tiny town. Or Dorothy if a tornado had dropped her in the Everglades instead of Oz. Or Alice if she had tumbled into a Wonderland populated by gators and ghosts and a man in a coat made of feathers. . . . A story rich in fantastic images and gorgeous language, anchored . . . by its wonderfully human characters and its big, warm heart.” —St. Petersburg Times

“A rich, lively narrative (sometimes silly, sometimes sad) with gorgeous language. . . . Russell’s debut novel shines with the glow of the southern sun.” —The Oregonian

“Funny, sorrowful, and engrossing. . . . Hardly a page goes by without the reader marveling. . . . An adventure story, a tale of family, a testament to resilience and an account of America’s homogenization, Swamplandia! is an accomplished and affecting debut.” —Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Unlike any story you’re familiar with. . . . A mesmerizing gothic portrait of love, death, and the loss of innocence.” —The Gainesville Times

“Russell’s writing is clear, rhythmic and dependable, even as her imagination runs wild.” —Los Angeles Times

“An astonishingly assured first novel.” —The Washington Times

“Some novels pull readers forward with plots that demand resolution; others make them want to linger on each sentence, bathing in the delights. Swamplandia! . . . does both, leaving readers with a sweet dilemma: Appreciate the present or forge on to find out what happens next.” —The Columbus Dispatch

“There’s simply no question that Russell writes beautifully, even about the darkest of truths.” —Time Out Chicago

“May be the best book you’ll ever read about a girl trying to save her family’s alligator-wrestling theme park.” —O, The Oprah Magazine

“Satisfying and heart-warming.” —Florida Times-Union

“Gorgeously written. . . . Russell’s flirtation with the fantastic adds a dangerous, off-kilter edge.” —Bookforum

“Intensely moving.”—The Onion’s A.V. Club, Grade: A

“[Russell’s] prose dazzles in any medium.” —The Philadelphia Inquirer

“Russell’s prose is beautiful, vivid, and lovingly creepy—just like Florida itself. . . . Magnificent.” —The Stranger (Seattle, WA)

“[A] wonderfully overstuffed, scaldingly funny, and frightening debut. . . . Read this book, pass it on to those who deserve it, and be thankful that the world contains artists like Karen Russell.” —PopMatters.com

“Exuberant, big-hearted, and entertaining. . . . In the midst of making readers think, Russell also makes us laugh, cry and gasp as she concocts an amazing and undiscovered world and populates it with characters we come to care for deeply. You’ll want to savor the sentences in this literary triumph.” —Maclean’s

Awards

New York Public Library’s Young Lion Fiction Award WINNER 2012

School Library Journal Adult Books for Young Adults WINNER 2011

Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction FINALIST 2012

Pulitzer Prize FINALIST 2012

The Orion Book Award FINALIST 2012

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In