Author Q&A

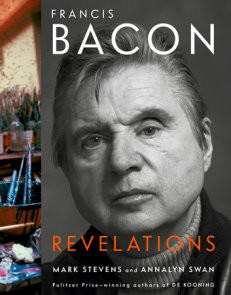

Q: This is the first major biography of de Kooning, who is widely regarded as one of the leaders of the New York School of art. What drew you to him?

A. To begin with, de Kooning is a seminal figure in 20th century art, but he has not been the subject of a serious biography. Today, many artists regard him as the last great painter–if not artist–in the Western tradition. The last to be schooled in the Academy. The last to lay on the paint in the grand style. The last great draftsman. The last great painter of the female figure. He has an inimitable "touch" and a bravura brushstroke.

But we were also drawn to him because he’s one of the rare artists to transcend the medium and become an emblematic figure in American culture. De Kooning embodies many classic American themes, notably that of the immigrant who comes to America, is desperately poor, and then succeeds–only to have success almost destroy him. In the 1950s, he became one of the first art world celebrities, with all the sex and swagger that implies. Walking with de Kooning through Greenwich Village was, a friend said, like walking with a movie star.

Q: Why hasn’t more been written on his life?

A: After the tremendous success of abstract expressionism in the 1950s, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and the other Pop, Minimal and Conceptual artists took art in a different direction. De Kooning, in particular, became a figure whom young artists and critics defined themselves against. It was not until the 1980s that de Kooning’s reputation began to soar again. But this re-emergence was clouded by questions involving his final works, which he painted while descending into an Alzheimer’s-like dementia.

Also, Elaine–de Kooning’s wife–re-entered de Kooning’s life in 1978 after more than two decades of separation. Elaine, while warm, witty and herself a talented artist and critic, was also extremely controlling. Until her death in 1989, an independent biography of de Kooning could not have been written.

Q: This book has been over a decade in the making. Talk a bit about the process of writing this. What sort of research did you do? Were you able to interview many of his contemporaries?

A: We wanted this biography to be as complete as possible, both about de Kooning’s life and his art. So we began at the beginning, doing research in Rotterdam Noord, where de Kooning was born in 1904. With the help of several Dutch researchers, we did extensive archival work on de Kooning, his family, the academy where he studied and the Rotterdam of his youth. Much of the research on his life after 1926, when he came to the States as an illegal immigrant, was done through interviewing hundreds of his friends and contemporaries, going back as far as the 1930s. Since we also wanted to set de Kooning firmly in the time in which he lived–we felt portraying a life in isolation tells only half the story–we also tried to reconstruct the cultural history of American art from the 1930s onward. The interviews with artists at the Archives of American Art were invaluable, too, since many in de Kooning’s generation had died by the time we began the book in the early 1990s.

Q: What kind of childhood did de Kooning have?

Very poor. His parents divorced when he was very young. He only saw his father very rarely. He was beaten by his mother, who was a histrionic woman who took up all the oxygen in the family. He was very close to his sister.

Q: De Kooning said to himself, when looking at New York’s skyline shortly after his arrival in America, "There’s no art here. You came to the wrong place." How much of this sense imbued his early work? Was this an inspiration to him or a hindrance?

A: That moment when de Kooning drove with an early friend up to Storm King, looked back over the city and said "You came to the wrong place" is actually an important turning point in his life. De Kooning originally came to America to make it rich, not to be an artist. He hoped to become a highly successful commercial artist. What he subsequently discovered, however, was that what he wanted to be a true artist. That had been his childhood dream as well, until the time when he became carried away, as many other young artists were, by the powerful new commercial and applied art scene emerging in Germany and the Netherlands in the 1920s.

De Kooning did not devote himself to painting full time until the mid-1930s, after a stint on the WPA. But the emphasis in his mind began to change as soon as the early 1930s. This is a book about, among other things, the evolution of a sensibility.

Q: De Kooning said, "I can’t see myself as an academic. I think of myself as a song-and-dance man." What did he mean by that?

A: De Kooning hated pretense and had a healthy suspicion of people-and institutions-who take themselves too seriously. He was, after all, a product of the working class who never got beyond a middle-school education and who lived for years in poverty and obscurity. He was never comfortable around the polished rich or the Establishment that offered honorary degrees and other prizes. He identified with another, more vital America–show girls, Times Square, constant change. Not the staid establishment.

By the way, de Kooning said many marvelous things during his life and that was one of the great pleasures of doing this book. Most artists are not great talkers, but de Kooning, who kept his Dutch accent, spoke a wonderful kind of broken home-made English, filled with puns and slang, which poets always loved. About classical art: “The Greeks hid behind their columns.” About his imitators: “They couldn’t do the ones that don’t work.” About the process of painting: “You pick up a paintbrush, and you have fate” (his way of pronouncing the word “faith”).

Q: Though many were impressed with de Kooning’s classical training, he was insecure about his academic background. How did this affect his work? Was it part of why he would destroy pieces and had such trouble finishing his paintings?

A: More than one of de Kooning’s fellow artists thought that his art was marvelous precisely because, as one put it, he was “forever in doubt.” He wasn’t insecure about his academic background. But his problem was how to be truly and authentically original and of his time. He struggled with facility and tremendous talent. He wanted something better and stronger than easy or conventional effects. To finish a painting was the hardest thing for him because he had stop changing it. "Every time I paint a picture I’m rolling the dice," he would say.

Q: Like many major artists, his real education–conceptually, at least–seems to have come from other artists. Picasso was one of the major influences upon him, helping him become a "modern painter", as you write in the book. How much did his peers influence him?

A: De Kooning once said, rightly, that he never painted a Cubist picture in his life. But for all artists who came of age in the 1920s and 1930s, the shadow of Picasso was inescapable. Elaine de Kooning, his wonderfully witty wife, once said that Picasso was like Sherman on his march to the sea–there was nothing left after he’d passed through.

While Picasso was a great influence, however, he was a distant one. De Kooning always said that he was tremendously lucky on first coming to America to meet the "Three Musketeers," as he called them–Stuart Davis, John Graham and Arshile Gorky. While the first two mattered greatly to him, it was the Armenian-born artist Gorky who was the most important to his development into a serious, and full time artist. De Kooning had a nearly religious experience when he first stepped into Gorky’s studio. Here, he had at last found a modern American artist totally committed to art.

Q: The later accounts of de Kooning’s life in the 1930s and 1940s, as well as that of his peers, talks about his poverty. How poor was he?

A: "I’m not poor; I’m broke," de Kooning liked to say, making a distinction between what he suffered in the 1930s and 1940s and the class-bound poverty he endured as a child. Nonetheless, his poverty–like that of his fellow artists–was very real before success came in the 1950s. It profoundly shaped his sensibility. Gorky described it as "crushing," and said no one who went through it survived intact. De Kooning and Elaine were often so poor that they could not pay the rent. They lived in cold water flats. They hid from the Con Ed man and stole electricity by tapping lines. They often had to decide between cigarettes and a square meal. The "outsider" status of the downtown artists became such a powerful bond that, in fact, it was very difficult for them to deal with success in the 1950s. Being on the inside made them extremely nervous–and prompted much of the drinking that beset them later in the decade.

Q: Did de Kooning’s relationships with women affect his work? Did he hate women, as is commonly thought?

A: De Kooning did not hate women. Quite the opposite. They were his muses. In the 1930s, de Kooning first painted a series of ashen men. But from 1940 on, after Elaine entered his life, de Kooning began to paint boldly colored, increasingly abstract figures of women. He returned again and again to this major theme. His women have many different moods: the ferocious Woman I of 1952, her more benign sisters painted later in the decade, the contemporary cuties in the 1960s, the great lush pastorals of the 1970s, in which the female figure becomes a kind of passionately charged landscape.

De Kooning was always perturbed, in later years, by the ferocity others found in Woman I and some of his other images. He insisted that he loved women, and that it was just his occasional irritation with them that came through. He also insisted on the funny aspect of his women, which he thought had been overlooked. They were part ancient idol, part Pop Princess.

De Kooning did not portray women “realistically” from the “outside.” Instead, he painted his sensations of the body. He saw the figure from inside. The pictures are not static. De Kooning had a kind of living relationship with what appeared on the canvas. At times, he almost seemed to make love to his subjects even as he painted them. You can see that in the caress of the brush, the tumescent build-up of paint, the distinctive flesh-tones of the paint. There was often a simultaneous connection and alienation–a love-hate, as it were.

Q: How did de Kooning feel about Jackson Pollock? Critics put them at odds. Did they have a contentious relationship? Why do you think de Kooning hasn’t had as high a profile in the mainstream as Pollock, despite the fact that they clearly shared the top slot of artists of their time?

A: Much has been made of the rivalry of de Kooning and Pollock–a rivalry fueled in particular by the critics Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, who helped make their reputation by championing one painter or the other. But de Kooning and Pollock were, above all, friendly rivals–first among equals. There’s a wonderful story about the two of them sitting on the curb one night in front of the Cedar Bar, the artists’ favored haunt in the 1950s, saying drunkenly to each other, "You’re the greatest painter, Bill." "No, Jackson, YOU’RE the greatest painter."

There are several reasons why de Kooning never captured the American imagination to the degree Pollock did. One was that Pollock busted out of the art tradition in a very fresh way with his famous “drip” paintings, while de Kooning held in many ways to the great traditions of Western art. For example, de Kooning wanted his paintings to be on the human scale–no bigger than his outstretched arms–while Pollock celebrated the mythic and grand. Pollock also became a romantic figure, a kind of cowboy who lived hard and died young in a car crash. De Kooning outlived Pollock by more than 40 years and died a death shadowed by dementia. But de Kooning tells just as important an American story: that of an immigrant who makes his way in the new world.

Q: Why was de Kooning such a tremendously powerful figure among the many celebrated artists of the New York School?

A: Because he was, in every sense, a painter’s painter. Nobody worked harder; nobody was more supportive of his fellow artists, especially younger painters; nobody had shown more determination through years of bitter poverty to be a real artist. He was so closely identified with the famous Club, which the artists founded in 1949, that it began to be called “de Kooning’s Club”–to the annoyance of some of his old friends.

Q: Describe a typical night at the Cedar Bar.

A: The Cedar was a bit of a dive, a place with garish fluorescent lights and beat-up booths, that the artists began to frequent in the early 1950s because it was near the Club. At first only the hardcore downtown artists–de Kooning, Franz Kline, Philip Pavia, Ludwig Sander–went. As the ‘50s wore on, however, everyone–artists, writers, critics–wanted to join the Club and hang out at the Cedar, and glowing articles about the downtown scene began to appear in magazines. The Cedar became a magnet not just for artists but Frank O’Hara and the New York poets–the group that one writer dubbed “the poets and the wits”–as well as such celebrities as Marilyn Monroe and Gloria Vanderbilt. The drinking went late into the night. There were fistfights and pickups. In one famous incident, Jackson Pollock pulled the door off the men’s room. Franz Kline once had 23 beers.

Q: Did the painters sleep around as much as the stories would have it?

A: As you can imagine, as the downtown scene exploded and the artists became boldface names, the art groupies followed. De Kooning and Elaine, his wife, began to live separately in the late 1940s, and each went their separate ways sexually throughout the 1950s. De Kooning’s most important relationship was with Joan Ward, the mother of his daughter, Lisa. But like the other artists, he had innumerable flings, especially as the decade wore on and the drinking became more and more maniacal. And of course de Kooning was the artist to sleep with. One person described it as bells going off all over the Village when de Kooning went on a bender, alerting young women that he was available.

Q: Once he moved to Long Island, de Kooning’s work never reached the same heights that paintings such as Woman 1 and Excavation did, and De Kooning learned that there aren’t any second acts in American life. Did he ever get over this?

A: Actually, we would argue the opposite–that de Kooning turned the cliché on its head and showed that there can be a second act in American life. It’s true that he had a down period in the 1960s, when he suffered an eclipse in reputation as the next generation became the great new thing. He was drinking heavily throughout the period, and uncharacteristically had trouble reinventing himself after the magisterial works of the late 1950s. Some of his openly sexual paintings of the 1960s are so graphic that critics were embarrassed by them. But then, in the mid 1970s, de Kooning began a series of great, sweeping pictures in which he essentially reinvented the pastoral tradition in American art. That would have been second act enough. But in the 1980s, he rallied from alcoholism to create one last final series, his controversial so-called "ribbon paintings." Many people love them. They capture what it’s like to be old. They’re the master’s good-bye, a kind of sublime emptying out, a whistling past the edge of the grave.

Q: How did de Kooning’s descent into an Alzheimer’s-like dementia affect his work?

A: The most important thing to say about de Kooning’s dementia, which began to be noticeable in the late 1970s, is that it progressed slowly, and not monolithically. In other words, there were good days and good periods balanced against bad days and bad periods. Dementia did not truly impair his ability until the mid to latter part of the eighties. We quote Oliver Sacks, among others, talking about the ability of artists even in advanced-stage dementia to maintain their "muscle memory," as it were, and still create great paintings. In a sense the 1980s are two separate periods–the early part of the decade, in which de Kooning began to empty out his canvases but retained the distinctive energy of his surface, and the latter part of the decade, when he began to churn out paintings, many of which appear more formless and clotted.

Q: What surprises you most about de Kooning? What were the most fascinating discoveries you made while writing this book?

A: The most fascinating thing about de Kooning, in the end, is that his art never really settles down. It can never be pinned down. He’s an immigrant who never stops moving. He was part European, part American, part romantic, part classical, part woman-hater, part woman-lover. Whatever was said of him, the opposite could be said as well. He was even ambivalent in his relationships, always avoiding a definitive break. You can imagine how difficult that was for the women in his life!

Q: What is de Kooning’s legacy? How will his work and contribution be viewed in 50 years?

A: He will be regarded as a painter who, in his earlier work, created a masterful synthesis of Cubism and Surrealism and then, bravely, threw away this blue chip style–to embark upon risky explorations of the figure and the landscape. He will be admired for creating a new kind of female figure and a new kind of pastoral landscape. He will be viewed as an artist with one of the great “hands” in art, a master of “touch” who developed an utterly distinctive brushstroke. He will be respected as a “painter” when many artists were losing interest in the craft of art. And he will be remembered, too, as a painter with an eternally restless eye. An existential wanderer.