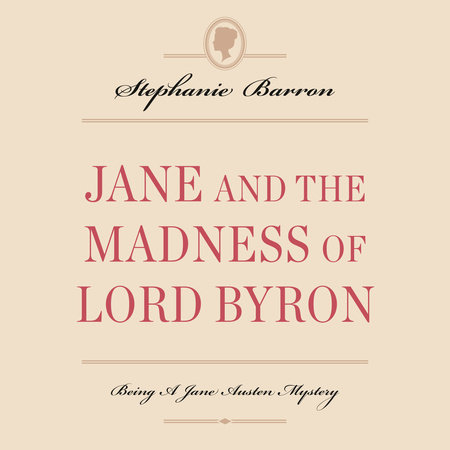

Author Q&A

A FEW QUESTIONS FOR STEPHANIE BARRON

Q: Your ten-book series about Jane Austen as detective has

carried readers through more than a decade of the novelist’s

life, from December 1802 to what is now the spring of 1813

in Jane and the Madness of Lord Byron. How closely do you

follow the historical record of Austen’s life, and how much

of the series is pure fiction?

A: Some of the books are so faithful to Jane’s letters that I’ve

used the actual calendar of her week as the structure of the

novel—and included everyone she mentions as a character.

But others, like Jane and the Madness of Lord Byron, are

complete invention. Although Jane chose Brighton as the site

of Lydia Bennet’s infamous elopement in Pride and Prejudice,

there’s no record of her ever having visited the town, for

example, and certainly none of her having met Lord Byron.

And to be fair, the man was never taken up for murder in

1813. But I knew Jane had seen almost every major town on

the Channel Coast over the years; I knew she read Byron’s

poetry—she refers to several of the poems in her letters, and

in her novel Persuasion—and they had acquaintances in

common. It was just within the realm of possibility for them

to meet. I like the realm of possibility; it’s the bedrock of all

my writing, and far more interesting than the known world.

When I saw that Byron was writing that spring about a

doomed love affair and a drowned girl—and that he made a

habit of sailing in Brighton—I knew I had to place Jane in

the town. And remarkably, at Byron’s death in 1824 he was

laid in state not at Westminster Abbey, which refused to have

him—but at the London home of Fanny Knatchbull, Jane

Austen’s niece. No one has ever explained why.

Q: Brighton seems like the last place Jane would be comfortable.

In fact, she derides it in Pride and Prejudice.

A: True. But she was always happy to go anywhere a friend

was willing to take her, which is why her brother Henry is so

vital to the story. Henry was fashionable and ambitious and

well connected to people in the Prince Regent’s set, who

would have descended on Brighton by April for the Royal

birthday. Henry would absolutely love the frivolity and display,

the pretty and available women, the horse races and

the crowd of gamblers at Raggett’s Club. Given that he was

in mourning—and that we know Jane spent both late April

and late May in London with him—it seemed logical to send

them off to the seaside during the intervening weeks, to recover

from the death of the incomparable Eliza.

Q: Was Byron as promiscuous as you suggest?

A: He was far more promiscuous than I suggest! He seemed

to require constant sexual stimulation, from a variety of

women—usually twenty years his senior—and young boys.

There’s a suggestion he forced himself on Lady Oxford’s

eleven- year- old daughter while staying at her estate, Eywood;

and he certainly had an incestuous relationship with

his half sister Arabella, and fathered one of her children.

When he eventually married Annabella Millbanke—a

cousin of Caro Lamb’s—the relationship lasted barely a

year. Although she would never disclose what Byron had

done to her, Annabella was probably physically and sexually

abused. Byron was not a mentally healthy man.

Q: Byron is called a mad poet in this novel, but frankly Lady

Caroline Lamb seems a bit more unhinged. How faithful to

the actual woman is your portrait?

A: Oh, my goodness—I was probably far kinder to poor Caro

than she deserves! I think today she’d be diagnosed as

manic- depressive. Or possibly a narcissist. Or both. She was

certainly volatile in her moods, violent in her rages, compulsive

in her attachments, and extreme in her selfdestruction.

A few months after Jane and the Madness of

Lord Byron ends, in July 1813, Caro put herself completely

beyond the pale of good society by attending a waltz party

at the home of one Lady Heathcote. She encountered Byron

in the dining room, and when he avoided her, she smashed a

wine goblet and tried to slash her wrists with the shards of

glass. She had to be carried screaming from the party, and

from that moment forward, she was rarely invited anywhere

again. William Lamb, her husband, nearly divorced

her that time—but he found it impossible to abandon Caro.

He sent her into exile at his family’s country estate instead,

which for Caroline Lamb was probably a kind of death-in-life.

Q: Speaking of death-in-life, how deeply attached was Jane to

her cousin and sister-in-law, Eliza de Feuillide, whose death

opens the book?

A: I think Jane was one of the few Austens, other than Henry,

who truly loved her. Jane was witty and sophisticated

enough to enjoy Eliza’s essential nature, which was frivolous,

fun- loving, and profoundly of the moment. Eliza connected

Jane to the Great World, and her kindheartedness

and intelligence would more than make up for any French

pretensions she persisted in displaying. The rest of the

Austens seemed to mistrust Eliza as a bad influence. But her

amusements were so tame—she never appears to have hurt

Henry in any way, and added greatly to his consequence and

comfort—that one wonders whether there was not a bit of

envy at the base of the family’s poor opinion.

Q: And yet Jane and Henry go on.

A: You had to go on, in those days. People died left and right.

In the course of her life, Jane would lose four sisters-in-law,

most in childbirth. She lost her father, of course, and her

close friend Madame Lefroy. And eventually the Austen

family would lose Jane herself, far too young. To be a citizen

of the world in 1813 was to be intimate with death.

Q: You make use of a very convenient tunnel in this book. Is

that an invention too?

A: Actually, no. The Prince Regent liked to get around

Brighton without being seen—particularly in his later years,

when he was obese and somewhat crippled by his size. He

had a number of tunnels built to and from the Pavilion, and

three of them survive in the present- day Royal Pavilion

complex, connecting modern concert and public performance

venues erected in the former stable block.

Q: What’s ahead for Jane Austen?

A: She’s going to travel to Kent in the autumn of 1813, for a

protracted visit to her wealthy brother Edward. At this

point in her life she’s publishing her third novel, Mansfield

Park, and gathering material for Emma, which she’s forced

to dedicate to the Regent! Kent is another secure and comfortable

world full of rich and famous families; but the Pilgrim’s

Way to Canterbury Cathedral also runs through

Edward’s estate, Godmersham Park. A mysterious stranger

will find his end there, in Jane and the Canterbury Tale.