-

$16.00

Jul 10, 2018 | ISBN 9781101902622

-

Jul 11, 2017 | ISBN 9781101902615

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

On the Road with Francis of Assisi

Carnivorous Nights

Duende

Kenneth Clark

The NPR Curious Listener’s Guide to Blues

Leonardo

Painting Below Zero

The Joy of Classical Music

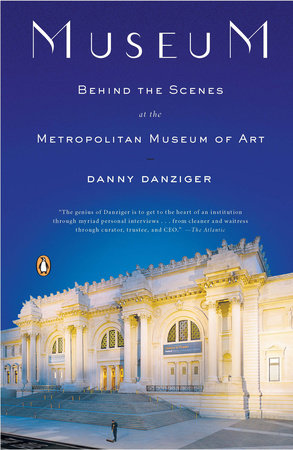

Museum

Praise

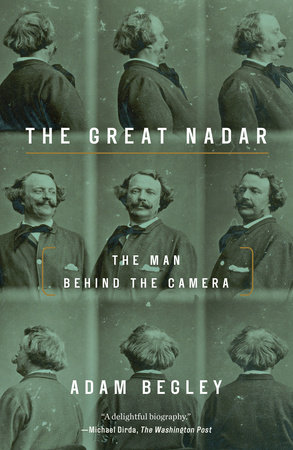

A New York Times Editors’ Choice

“Irresistible. . . . A richly entertaining and thoughtful biography. . . . Begley seems wonderfully at home in the Second Empire, and shifts effortlessly between historical backgrounds, technical explanation, and close-up scenes, brilliantly recreating Nadar at work.” —Richard Holmes, The New York Review of Books

“Concise and thoughtful. . . . Begley delivers a subtle accounting of Nadar’s career as a photographer while reminding us of his subject’s many other talents and exploits. . . . This book, like Nadar’s life, roars past with a whooshing sound.” —Dwight Garner, The New York Times

“A delightful biography. . . . It comes across as a labor of love. Yet the word ‘labor’ hardly characterizes the suavity, swiftness and economy of its text. The book is a pleasure to read, though one could almost buy it just for the pictures.” —Michael Dirda, The Washington Post

“A window on an era of extraordinary artistic endeavor. . . . Mr. Begley has combed through an array of literature, letters, guest books, invitations, drawings and other miscellany to tease out a nuanced portrait of one of the world’s first celebrity artist-entrepreneurs.” —Tobias Grey, The Wall Street Journal

“A taut, engaging biography. . . . Begley creates a vibrant portrait of Second Empire Paris through one of its most colorful characters.” —The New Yorker

“A short, beguiling book. . . . Begley writes briskly, jauntily, and affectionately about his subject.”—Michèle Roberts, The Times Literary Supplement

“Masterful. . . . Begley’s vibrant new biography tells Nadar’s story in all its colorful detail. . . . We can be grateful to Begley for capturing some of that quicksilver spirit, that quintessentially Parisian sensibility, which left us with images that are, in their bewitching way, timeless.” —Thad Carhart, Newsday

“A sympathetic and judicious book. . . crammed with character and incident. . . . Nadar was one of the greatest portraitists in photographic history. . . . He would have been very much at home in our day.” —Luc Sante, The New York Times Book Review

“If genius is the capacity to astound, then Nadar is up there with the greatest. . . . With this book, Begley . . . puts him back where he truly belongs. . . . Battered into submission by the man’s glorious character, towards the end of this book I arrived at the last known photograph of him—an old man in his garden, a newspaper in his lap. I teared up, realising that Adam Begley had made me love him as much as he evidently does.” —Bryan Appleyard, The Sunday Times (UK)

“A joy to read. . . . The best part of the book is the ease with which Begley is able to relay the artist’s life story and its many intrigues.” —Hyperallergenic

“A superb account of one of the nineteenth century’s most irrepressible spirits. Nadar was the founding genius of photography, especially portraiture, a heroic, disaster-prone balloonist, as well as a journalist, cartoonist, would-be revolutionary and one of the first ‘bohemians’. Adam Begley brilliantly evokes the Paris of the Second Republic and Second Empire, its gloriously impoverished and eccentric artistic milieu, its squalor and political turmoil. Nadar knew everyone and took the photographs of the men and women who defined the era. Here the best work is excellently reproduced and discussed with great sensitivity and insight; from every point of view The Great Nadar is a beautiful book.” —Ian McEwan

“Nadar described himself as a reckless enthusiast, a hyperkinetic presence, every father-in-law’s worst nightmare, someone who ‘never missed an opportunity to talk about rope in a house where someone has been hanged or ought to be hanged.’ That was nowhere near the half of it. Adam Begley fills in the rest, providing a portrait every bit as seductive as was its irresistible, irrepressible subject.” —Stacy Schiff

“Adam Begley has found the perfect biographical subject in Nadar—an irrepressible artist, a daring pioneer, a wild-eyed visionary, an outrageous self-promoter, and an enfant terrible, who, like some sort of Zelig, seemed to turn up alongside every major figure in Paris during the heady period of the mid-nineteenth century. But what makes this book so mesmerizing is Begley, who, with his own artistry, brings Nadar roaring to life on every page.” —David Grann

“A completely fascinating, thoughtful and most elegantly written biography of one of the great early photographers.” —William Boyd

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In