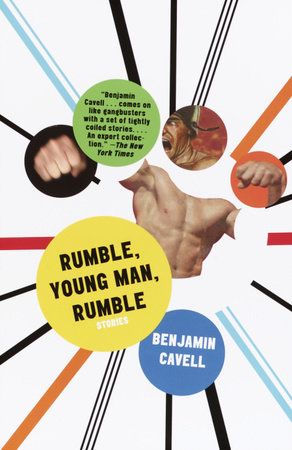

Author Q&A

A Conversation with Benjamin Cavell

Author of RUMBLE, YOUNG MAN, RUMBLE

Q. You’ve created a world of men who often seem consumed by violence and sex but are also yearning for answers. What made you want to explore what it means to be a man?

A: In large part, I think, it was my perversity. That is, I want to write about what it means to be a man to some degree because that subject is so out of fashion. The most striking effect of that trend is that it is possible (and maybe even likely) to graduate from an American university these days without ever having been assigned Hemingway. And yet there may not be a 20th-century writer who has had more influence (positive and negative) on the generations that followed him.

The world my men inhabit is awfully crowded and dominated by extra-human technology (in which elevators speak for themselves) and by rules of behavior that are made more restrictive because it is so difficult to know what specifically they are. This is not to say that I think technology is so bad; I don’t. I also don’t think violence is so bad. I know that there are people who argue that the world would not be in its current state if human beings could somehow eliminate their instinct for violence. I don’t know that it’s even worth arguing this point, since it seems just as likely as eliminating human beings’ need for sex or food. (I am reminded of the character in Slaughterhouse Five who says writing an anti-war book is like writing an anti-glacier book.) I can’t imagine all the conditions that would have to be met for human beings to eliminate violence (wouldn’t they include the death of evil and good, sadness and joy?). The only answer I can give to such a criticism is that I want to live in a world with things in it that are worth fighting for. For me, the real argument concerns what those things are.

Q: Evolution immediately brought to mind recent news events, namely the sniper killings in Washington. Do you feel that this story offers any kind of an explanation for events like that?

A: I guess it would be fashionable to say that fiction can never explain the kind of evil or amorality shown in the sniper killings. But I think good fiction should offer an explanation for—or, better, a way of understanding—any human action. (I am often struck by the passion with which people try to deny the power of fiction. Robin Williams’ character in “Good Will Hunting” rhetorically asks Matt Damon’s character, an orphan, “Do you think I have the slightest idea how hard your life has been because I read Oliver Twist?” But what marks Dickens as a great writer except his ability to give us more than the slightest feeling for the lives of other people?) That said, I’m not sure the sniper killings require much explanation. I don’t mean to sound reductive—I tend to agree with the statement (although I can’t seem to remember its author) that totalitarianism is, at its root, the attempt to apply easy solutions to complex problems. All I mean is, how hard is it to understand that a certain combination of loneliness and depression and desperation can lead a man (and the boy he has taken under his wing) to kill at random? In fact, I would think it’s much easier to kill a person who is only a tiny figure in your gun sight whose face you can’t even see than to stab someone and look into their eyes as they die. For some people, explaining actions is akin to excusing them. That is not the case for me. I regard Muhammad and Malvo each as terribly sad in some way and yet I feel no mercy for them. I think being a good writer (not to mention an intelligent person) requires that one be honest about the world and admit that there probably is no absolute evil or absolute good and that one can feel sorry both for a murderer and for his victim.

Also, just as it is a mistake to think of rape as being about sex, I think it’s a mistake to think of the sniper killings as being about violence. They are about power. In Evolution, the characters regard killing both as a source of power (there is a discussion about the power they wielded over the family they decided not to kill) and as a kind of last frontier for the modern man in his attempt to return to his natural state—they are trying to eliminate conscience as a censor to their actions and killing is the ultimate transgression.

Q: To what extent did your experiences as a boxer inform the story, THE ROPES, and this book in general?

A:The story that Alex tells in The Ropes about being five years old and having his father bring him a tiny pair of gloves and then kneel on the floor in front of him and say, “Hit me,” is almost the actual story of the day I learned to box. The only real difference is that it was not my father who taught me to box but an old friend of his named Kurt Fisher, who had grown up in Vienna and fled to Shanghai with his mother when the Nazis came. Apparently there was a boxing league in Shanghai (made up, I think, of British sailors) and Kurt beat whomever there was to beat in their middleweight division and became middleweight champion of China. So it was a former champion (sort of) who showed me the basics of boxing. Somewhat later, Hemingway and Muhammed Ali each taught me ways that boxing could be turned into a literary subject. And somewhat after that, Tommy Rawson, the Harvard boxing coach, told me his stories and taught me that I had a talent for boxing that most people did not have.

I’m not sure to what extent my experiences as a boxer inform the stories that are not about boxing. Probably boxing has given me a more realistic sense of violence. It has also given me a confidence, which I think comes through in my writing, that I otherwise might not possess.

Q: Race and class are components of nearly all of your stories. Why do you keep coming back to them?

A:Race and class are two of the great subjects and particularly two of the great American subjects, and yet it seems difficult for anybody to say anything interesting about them. I try to have race and class be part of the fabric of my stories without being the focus. I think fiction that is explicitly about race (or racism) and class tends, even when it’s written by great writers, to feel preachy and over-simplified. Also, fiction like that often relies on symbolism in place of reality, perhaps because problems of race and class seem so insoluble. I don’t regard it as the job of fiction to solve those problems, only to show them more clearly and thereby to influence people’s thinking about them.

As for the question of whether a white, middle-class man ought to take on those subjects (which is a question one often hears), the easy answer would be that any writer should have the right to write about anything. A more controversial answer is that most literature comes out of a struggle between guilt and longing, and children of the middle class tend to have grown up wrestling with their shame at being well-off and their desire to be better-off.

Q: “Any of the people you pass on the street could pretend to trip and stumble into you and sorry sorry my mistake pour a glass full of cyanide into your bare forearm . . . You are at their mercy. You are alive because they want you alive or because they do not care whether you live or because they do not notice you . . . You rely on the kindness of strangers.” This opening passage to THE DEATH OF COOL is a frighteningly dim outlook. I literally shuddered as I read it. Is this something that you think of often?

A:I’m not sure that I think of it often, but I’m certainly aware of it and it’s easy for me to imagine a character who has become paralyzed by his fantasies of the dangers that surround him. In some way, I think The Death of Cool and Evolution come from similar impulses in me—The Death of Cool is about all the things other people don’t do to you; Evolution is about all the things you don’t do to other people.

I suppose I ought to say that The Death of Cool was written in response to September 11th (which is true to an extent), but I had been trying and failing for some years to write a story in which the protagonist suffered from that kind of paranoia. I wrote the opening passage almost in its final form shortly after I graduated college. In fact, in the original version it was anthrax (not hantavirus) that the narrator tells us could be released in the subway. I changed the reference after the real anthrax attacks, in part because it would have felt cheap to leave it in and in part because I think the power of paranoia is that it is not limited by reality.

Q: Comparisons are already being made between your writing and that of Ernest Hemingway and Norman Mailer. How do you feel about this, and who are your literary heroes?

A:Of course, it is impossible to respond directly to such comparisons. You can either say, “Thank you!” which may suggest that you don’t feel worthy of the company (death, I think, for an ambitious writer) or else say, “I don’t want to be the next Ernest Hemingway, I want to be the first me,” in which case everyone will (rightly) hate you.

Hemingway and Mailer have been tremendous figures for me since I was fourteen years old and beginning to think seriously about what it would mean to be a writer. Their influence has been at turns inspiring and stifling, so comparisons of my writing to theirs can make me worry that I have slipped into the trap of imitation. I hope that the comparisons come from a more general sense of similarity in our subjects and maybe even in the size of our ambitions.

It took me a number of desperate years to get out from under the Hemingway style. I found it (as, I think, did Mailer) madly attractive and madly limiting. There are themes one might want in one’s work that seem unable to exist inside the hard muscles of Hemingway’s sentences. The major writer in the second half of the last century had to be responsible for an enormous breadth of subjects, particularly Philosophy, many of which would not have interested Hemingway. And this new, post-9-11, world seems even more complicated, for an American, than the Cold War world in which Mailer did much of his writing and in which we better understood our enemies.

I don’t want to give the sense that all of literature is, for me, to be found somewhere between Ernest Hemingway and Norman Mailer. There are many other writers I admire (often for their energy and honesty and lack of sentimentality), in addition to those (Homer, Shakespeare, and so on) whom one does not really have the right to admire or not admire.

Q: The women in your stories range from simple objects of desire or fascination to figures that have a strangely powerful hold on male characters. Why do women seem so peripheral in your work?

A:I’m sorry to hear that women seem peripheral in my writing. They are certainly not peripheral in my life or in my thinking about the world. If I don’t write much about women, it’s only because I feel as though there are other writers who have written about them better than I can. I don’t yet have a lot of interesting things to say about women that haven’t been said before. I think the saying “write what you know” is often misinterpreted as “only write about things you have actually done.” I take it much more to mean, “write what you understand well enough to be interesting about as you work to understand it further.” I intend to write more about women, but I don’t want to do it just because I ought to and to be forced to lean on clichés or to rehash other people’s work. I figure if I don’t have anything new to say, I shouldn’t say anything at all.

Q: You’ve offered us serial killers, football superstars, Jamaican “yardies,” stressed out politicians, struggling artists, and a few guys with some severe mental problems. Your portrayal of each seems so effortless; what’s your secret?

A:The kind of imagination that interests me most is moral imagination—that is, the ability to imagine what it’s like to be the other guy. (I am often thrilled by the imagination required to create “Star Wars” or Dune or even The Lord of the Rings, but that kind of thing often feels like cheap, hot, tasty, fast food that leaves you hungry an hour later.) I think a well-developed moral imagination may be the most important quality in a good writer. I also think that the reason there have been so few good upper-class writers—I mean writers from the upper class, because of course there have been many who have written well about it—and so few good totalitarian writers is that each group tends to lack moral imagination.

It is not difficult to see, superficially, what is desirable and what is frustrating about most lives. After that, one can begin to imagine the internal life of a character in a given set of circumstances. It is more difficult, of course, to create a character who is unlike you not only in circumstance but in personality—a killer, for example. But most people have in them the capacity to be good and evil, kind and sadistic. In order to create an aberrant character, a writer (like an actor) takes the mostly unused piece of himself that is the dominant feature of the character and extrapolates what it might be like to be controlled by that piece.

There are some things one can make oneself learn about writing. But I often think that moral imagination, like an ear for authentic-sounding (which does not necessarily mean good) dialogue, is something one either does or does not have.

Q: Having been a teacher, what advice do you have for other young writers?

A:Don’t be sentimental; it’s cheating. And don’t use adverbs (or italics), unless you absolutely need them.

Q: What’s next for you?

A:I hope that what’s next includes watching the Red Sox win their first World Series title in eighty-five years. More likely, I will make my annual journey from the wild optimism of March to the despair of September when the joy leaves Mudville and the Sox fade from the pennant race. Also I’m at work on a novel, which I hope to finish this spring or summer.