READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

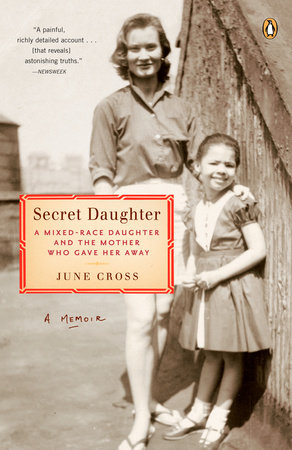

Secret Daughter

The relationship between a mother and daughter is often complicated, fraught with frustration as much as it is fortified by love; the relationship between June Cross and her mother Norma was exceptionally so. In her memoir Secret Daughter: A Mixed Race Daughter and the Mother Who Gave Her Away, Cross, a journalist, television producer, and university professor, shares the story of her struggle to understand her mother and thereby learn to accept herself.

Growing up during the Civil Rights era, Cross exists at the intersection of race in America, and her private life parallels the country’s racial coming of age. While the social landscape is dotted with school integrations and marches on Washington, Cross’s home is the situation for a more private and high-stakes battle for black-white relations. On one side is her white mother Norma, the woman who gave her up, alternately ashamed and ignorant of her daughter’s black identity; on the other, her black aunt Peggy, the woman who raises her, teaching her to appreciate her racial heritage yet unable to accept the social progress of her time. In their own ways, both women love and care for Cross, however both leave her with something lacking. She feels compelled to make decisions she is unable or unwilling to make: Should she obey her aunt or her mother? Who is her real family? Who will accept her? Who can she trust?

As Cross matures, she slowly unravels the history behind her life story, reconnecting with her father and discovering the true nature of her parents’ relationship. Anxious to learn more, Cross realizes that the person who holds the key to the information she seeks is the person at the center of it all—her mother. Using her journalistic training, Cross begins to research her mother’s identity, creating a probing documentary for Frontline in which she examines her mother’s actions, highlighting the complicated web of demands race has forced on people in America over the past forty years.

Moving from a childhood marked by deception to the mature self-acceptance that only the truth can bring, Secret Daughter is a fascinating and intimate look at race, relationships, and personal identity. Cross’s tale of the hardships endured and inflicted by her mother is shocking, even heartbreaking, yet the love that Cross continues to feel for her mother shines through the entire book and the connection between mother and daughter—no matter the difficulties—is undeniable.

ABOUT JUNE CROSS

June Cross is assistant professor of journalism at Columbia University. She has been a television producer for Frontline and the CBS Evening News and was a reporter, producer, and correspondent for PBS’s MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour.

A CONVERSATION WITH JUNE CROSS

Q. After having produced the documentary for Frontline, what prompted you tell your story in book form?

A. The documentary was an extremely focused piece of work that concentrated on my mother’s betrayal and my attempt to uncover the truth of it. In the process, however, we had to leave out much about the black family that did raise me, that provided an identity for me and which loved me, giving me the strength to withstand the schizophrenic life I lived. I wrote the book to tell that larger story, and hopefully answered two questions which emerged from the documentary: how did I really feel about my upbringing and my mother—and how did I survive psychically?

Q. What are the differences in the creative process of telling your story as a filmmaker and as a writer? How do you feel the content and effect of the story have been altered by this change in medium?

A. Films tell external stories; books tell internal stories. Documentary films focus on facts; books focus on feelings, impressions. I had to spend a long time ruminating about how I actually did feel about this experience, literally writing my way to the marrow of it. Television writers also write much differently. We strive to write short, and research deeply so that we can write succinctly and accurately. Additionally, we have those pictures, worth a thousand words, which provide a number of cues: body language, facial expressions; the pause between words as an interviewee struggles to articulate her thoughts. These all provide subconscious cues about character. In a book, you can’t see any of that. You have to describe it—but not all of it; you must choose the moments that illuminate and develop the theme the author is trying to convey.

It was nearly impossible on paper to capture my mother’s charisma. I’m just not practiced enough in that medium. I do think I was able to convey her narcissism but not the witty intelligence that she brought to any relationship. The same with Aunt Peggy—she had a wicked sense of humor and a great sense of compassion which those older than I remember but which I also had great difficulty conveying.

Q. Throughout the book, you include conversations and other details that seem impossible to completely re-create. How did you decide how much creative license to allow yourself in presenting the past? Were there any struggles between factual accuracy and narrative style?

A. I had a wealth of information: letters between Aunt Peggy and Norma; diaries I had kept since the age of eleven; a trove of pictures of all sides of the family; and I had the interviews that I had done for the documentary. Some scenes I developed with participation from those I had interviewed previously. I went back to my classmates at Indiana Avenue School, for instance, and asked them for their remembrances of Mrs. Cotton. I did the best I could to triangulate the conversations.

There were, of course, conversations I couldn’t triangulate, because the persons involved have died—those with Aunt Peggy and Uncle Paul—the conversation with my father at his deathbed. These I wrote while in something akin to a meditative state, free writing my way through them while holding what I knew about their characters in my conscious and striving to put myself back in the shoes of the person I was. I fact-checked everything and did my best to honor their character as best I had reported it, and as best I could remember it.

Q. Your Aunt Peggy died in 1982; your mother passed away in 2003. In what ways has each of them continued to influence your life? What do you think their opinions of your book would be?

A. Aunt Peggy once told me that I would grow up and write this book and make her the villain. I hope I haven’t done that, even though, by circumstance, her authority was the one I rebelled against. She often told me that I could be whatever I wanted to be, but she was a conservative at heart, and I sensed that her greatest aspiration for me was to get married and have kids. She did not want me to have a professional career, although she was fine with the idea of me working. I think had she been my biological mother, I might well have become a music teacher in some suburban life.

My biological mother, on the other hand, brought to the enterprise of raising me that sense of entitlement which American whites have, and she instilled it in me. She exposed me to the world beyond Atlantic City; it’s a world I still yearn to explore. Mom just wanted me to finish the damn book, even if meant she would emerge as the villain. She gave me permission to roam the world, to express myself; to test the limits of what was expected. Frankly, I still feel torn between the two of them. One side of me seeks security and a sense of belonging; the other is more of an adventurer and runs away from commitment. I’ve tasked myself with spending the next phase of my life attempting to merge the two.

Q. Having broadcast the Frontline documentary, you’ve already experienced public reaction to your life story. What kind of responses did you get initially?

A. Overwhelmingly positive; although many viewers wanted to know how I felt about the way I was raised. Many people ask me for advice about how to raise trans-adopted children. I tell them to give them a sense of their own history so that they have the strength to stand against the onslaught of American homogeneity.

Q. Is it difficult to place yourself and your loved ones in public scrutiny?

A.I just pretend I am writing about somebody else. There’s a schizophrenic aspect to it.

Q. How did you prepare to handle this sort of attention again with the publication of the book?

A. I’ve become a connoisseur of single malt scotch.

Q. What experiences do you hope readers take from your life story? Is there a lesson to be learned from your book?

A. My biggest challenge was allowing both of my mothers their humanity, and their ambiguity. I would like to think that the book makes readers aware that we all have our good and bad qualities and that those ambiguities don’t make us less worthy of love, just more human.

Q. How would you characterize the current state of race relations in America?

A. Race remains the national neuroses, but I think September 11, 2001, transfigured the landscape of race relations. Muslims and Mexicans have now become the new “other.” While the majority of black Americans continue to face tremendous obstacles, I think we have entered an era in which the definition of who is American includes African and Caribbean immigrants; and a biracial African American is even running for president! That would seem to indicate progress, but in fact what I think has happened is a reconsideration of privilege in which some of us so-called “mainstream” blacks have become like honorary whites, in that we are now allowed access to the American dream, assuming that we can prove our worth in terms of education, politesse, credit score, etc. Meanwhile, the historical position of the black as “less than” has become the yoke borne by a group of poor Americans who may look Arab, black, white, or Latino. This is not to say that a middle class black man still can’t get shot by the cops in a case of mistaken identity, it is to say that the terms of the conversation have gotten even more complicated. It makes the work of developing language with which to discuss our differences all the more important and makes the need for compassion imperative.

Q. You clearly have a strong sense of who you were as a child and young woman, and how you arrived at the life you have today. If you could say anything to yourself as the girl at the heart of Secret Daughter, what would it be?

A. Be fearless. You are worth more than you think. You are enough, you have enough talent, to do whatever your heart desires.

Q. What’s been happening in your life since the end of the memoir?

A. I was tenured at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, and I’m studying the Chinese art of Feng Shui. A number of book clubs and organizations have asked me to come speak, and I try to oblige as many as I can.

Q. What is your next project?

A. I’m currently working on a film that follows an extended family from New Orleans as they try to rebuild their lives post-Katrina.

Q. Can you see putting yourself at the center of your work again in the future?

A. I have developed a first-person narrative style in my documentary work. I have thought about writing a part two of the memoir but that is probably an effort that’s some years away.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS