READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

Launched with a three-month stay on the New York Times hardcover bestseller list, In the Company of Others follows Father Tim Kavanagh—now retired from tending his flock—as he makes good on a promise to show his wife, Cynthia, the land of his Irish ancestors. In a charming fishing lodge in County Sligo, any hope for a peaceful sojourn is dashed by an intruder, a stolen painting, and a bitter family conflict dating back three generations. New and old fans alike will be riveted by this compelling tale of the desperate struggle to hide the truth at any cost and the powerful need to confess.

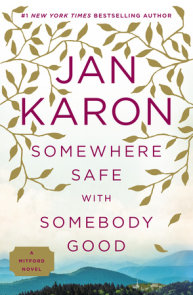

ABOUT JAN KARON

Jan Karon is the bestselling author of the Mitford series and Home to Holly Springs. She lives in Virginia.

A CONVERSATION WITH JAN KARON

Q. What strikes one immediately when reading this novel is the emphasis on language—particularly the lyrical voices of the Irish characters. Can you talk about how the Irish vernacular has inspired your writing?

Irish vernacular is full of color and surprise, metaphor and double meaning. I grew up on remnants of this speech because our North Carolina mountains are populated with people of Scots-Irish heritage. I had heard it all my life, in a form diluted by time, but still resonant of the original and full of sap.

Q. Tell us about your travels to Ireland and interactions with its people. What were some of your favorite experiences?

I love the country house hotels, where either Irish or English family descendents are trying to make a new living off old ground. No chain lodgings, no commercially driven meals, no expanses of asphalt and industry, but (usually) innkeeper descendents of the original owners, gorgeous views, family pride, food from their own gardens or sheepfolds or local farms, and, if one has Irish blood, they may end up treating you like family.

Q. You clearly did a lot of research into medical practices in nineteenth-century Ireland. How did you go about it? What were the more surprising things you learned?

I learned what a scamp Dr. Wilde was (I enjoy gossip laced with history), how rare was the man with the gall to pull teeth for the populace (one usually had to do it oneself), how innocent they were about germs, for Pete’s sake, and I can’t think what else. I loved living in that time period through my writing and research. I never intended to go on about Fintan O’Donnell’s life there, but he kept at that journal and so did I. My favorite character next to the good doctor himself was, of course, the Lad. He was my Dooley of decades past.

Q. Dr. O’Donnell’s journal is a fascinating part of the novel—it’s a treasure trove of history and a portrait of life in a bygone era. Why did you decide to incorporate it into the book?

I needed a place to hide what had to be hidden, and the theft needed to be more complex than a random robbery—if only to keep the author interested. The journal simply spread out over years and other lives as dandelion seed dispersed on the wind.

Q. W. B. Yeats figures prominently in the book. Aside from those mentioned in the novel, which of his works would you recommend to your readers?

Might as well get the complete works and go at a run with it. It makes one giddy, like spinning around and around, then stopping and falling over.

Q. Early in the novel, you have a refreshingly candid admission of the emotional toll the priesthood takes on Tim as he realizes that his heart is exhausted by a life of giving to others (p. 96). Yet he continues to minister to the Conor family. As you have explored Father Tim’s character throughout the novels, how have you come to understand this trait of his?

He can’t help himself. He is attracted to suffering and grief and loss and there’s no way around it. God wired him this way and he has learned to just go with it—doesn’t resist it, just gets into whatever is calling him out and gets to the heart of it if it can be done. He is a kind of warrior who, when he hears the battle cry, is on his horse and into the fray and devil take the hindmost. As Cynthia says to him, ‘I do books, you do people.’

Q. When we travel, as Father Tim and Cynthia do here, we learn about the places and people we visit, but we also learn about ourselves. How has this trip changed the not-very-adventuresome Father Tim?

I’m not sure it has changed him. When the next book opens, we find he is very happy to be rooted once again in Mitford ‘like a turnip.’ No, he will not be seeking any more adventures. Any adventure will have to come to him—which, of course, it most certainly will.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS