READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

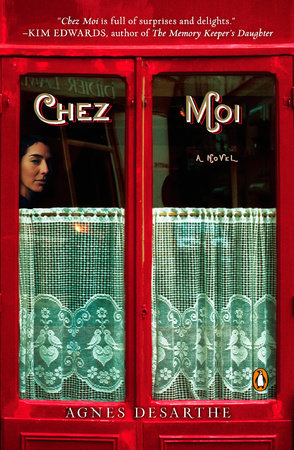

Forty-three years old, trailing secrets and extravagant lies, Myriam has just convinced a bank to give her a loan to open a small restaurant in the Eleventh Arrondissement of Paris. Chez Moi is a modest place, but the name alone signifies its importance. Too poor to rent an apartment, Myriam must live in the restaurant, sleeping on a banquette and bathing in the (thankfully) deep kitchen sink. The restaurant could be her last chance to create a new, stable life for herself.

Six years earlier, Myriam did the unthinkable; she initiated an affair with her son Hugo’s friend. Humiliated and embarrassed, and unable to make amends, Myriam decides to leave her family. With her only possessions, a small suitcase and a thirty-three book library, she managed to secure a position cooking for the Santo Salto circus. The misfits and talented strays of the circus gave her a home, but they could not shelter her from her past indiscretion. Myriam had to find her own way back into the world.

With the establishment of Chez Moi, she cautiously opens her life back up for business. Still tender from the loss of her family, she has little faith in herself or in the future of her restaurant, and is skeptical of the people around her. Despite her misgivings, she puts all the love that she cannot give her family into the food she prepares. Gradually, whether she wants to admit it or not, the restaurant begins to change her.

Myriam has always felt that her life has been predetermined, but with the opening of Chez Moi, things begin to take a positive turn. Ben, an outwardly awkward yet astoundingly graceful waiter, appears at the very moment she needs him, and Vincent, the uptight florist next door, becomes her dear friend after a fraught beginning. Though she is a self-taught cook, her dishes are skillfully executed, and her vivid dreams and intoxicating visions for the restaurant create a haven for the local community. But as her success grows, so does her fear that her life could crumble again, leaving her with nothing.

By reaching out to Ali, a farmer whom she knew during her years cooking for the circus, Myriam hopes to bring his magic to her new venture. But Ali does much more than transform her kitchen; he transforms Myriam’s entire perspective, allowing her to love again. And when, after six years of silence, her son seeks her out with the help of the new love in his own life, Myriam finally begins to make peace with herself.

ABOUT AGNÈS DESARTHE

Agnès Desarthe was born in Paris in 1966 and has written books for children, teenagers, and adults. She has had two previous novels translated into English: Five Photos of My Wife (2001), which was short-listed for both the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize and the Jewish Quarterly Fiction Prize, and Good Intentions (2002). Chez Moi is her first book to be published in the U.S.

A CONVERSATION WITH AGNÈS DESARTHE

Q. In Chez Moi, you deal with serious themes of maternal and romantic love, betrayal, and redemption, yet despite the difficult subject matter, you generally keep a light or even fable-like tone. Why did you choose to write the book in this way? Did you purposefully set out to make Chez Moi a positive, redemptive story, or did that notion evolve during the course of your writing?

Keeping a light tone has always been my way, whether I’m writing for children or for adults. It’s a question of both aesthetics and culture. To me, humor is one of the most exciting literary devices.

“Redemptive” is not a word I would use. A book just has to end. Isaac Bashevis Singer used to say that in literature as well as in dreams death did not exist. I always have this in mind. There is something utterly not serious in fiction.

Q. You write so evocatively about food; it must be a love in your own life, in some form. Are you a cook yourself? Why is food such an integral part of this story? What did you hope to convey by making Myriam a chef?

At one point in my life I noticed that I spent more time cooking than writing. I love cooking, but still, I found it alarming. I started wondering what the problem was with me and realized that when you cook, you do it for people who are hungry. The average human being is hungry three times a day. That’s an awful lot. When you write, nobody seems to be especially hungry (for fiction, I mean). There’s something absurdly romantic in keeping up this activity. I often say to myself that my life would be happier if I were a cook.

The reason why food is so important in the novel is because it allows the perfect give-and-take relationship that will always be missing in art. Myriam is a chef because she has a problem with desire. Cooking is the only way she has found to give herself to others without being too threatening. In France the book is called Eat Me. The sexual tension is made much more obvious than in the English title.

Q. Myriam is a voracious reader and many of her favorite books are mentioned in Chez Moi. Which books have the most personal resonance for you? Are your tastes similar to Myriam’s?

All of the books that are mentioned in the novel are part of my ideal list—but that list includes many more than thirty-three volumes.

Q. You started as a translator, and you’ve now written many children’s books, two plays, and this is your sixth novel for adults. Is there one form you enjoy most? Do you still work in all of these forms?

What I enjoy most is going from one form to the other. I don’t think I’ll ever stop translating or writing for children. Recently I’ve translated Cynthia Ozick’s The Puttermesser Papers and Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room, and both were such nourishing experiences that I don’t see how I could do without them. It gives me the impression that I’m a better writer than I really am, and it’s ego-free work, which is a wonderful holiday for an artist.

Q. What other writers have most influenced your work? If not a direct influence, who do you admire?

That is a particularly difficult question. Very often, in magazines, I read interviews in which the author cites Flaubert, Dostoevsky, Faulkner (very few women in general), and I think, “Wow, he must be really good having received such wonderful influences,” but once I get down to read the actual work, I’m disappointed. I’ll answer all the same, because, as we say in French: Le ridicule ne tue pas (ridicule never killed anyone). I admire and would gladly be influenced by: Virginia Woolf, I.B. Singer, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Primo Levi, Cynthia Ozick, Henry Roth, Marguerite Duras, and many, many more.

Q. What are you working on now?

I’m translating Gail Carson Levine’s Fairest, and writing a novel for teenagers about three issues that torment me: beauty, adulthood, and novel writing.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS