READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

Philip Mazryk never made much time for literature. Until now, the two most consistent passions of the mathematician’s emotionally itinerant life have been running and numbers. They were the mechanisms through which he processed the world. This is all about to change when Irma Arcuri—reader, writer, bookbinder, and Philip’s sometime lover—disappears, leaving him both her extensive book collection and a mystery as dizzyingly seductive as Irma herself.

Philip and Irma have long shared an unusual intimacy. Brought together by a passion for running and their inherent maverick sensibilities, the math genius and the literary renegade have been friends since college. And, although both have had numerous other romantic relationships, they have remained lovers, often sharing sexual partners—including Philip’s two ex-wives.

When Philip learns of Irma’s disappearance and the unexpected bequeathal of her library, he begins making adequate physical and psychic space in anticipation of the books’ arrival—first quitting his job as a number cruncher at a Philadelphia insurance agency and then acquiring and sparsely outfitting an apartment in which to read. The collection itself is physically stunning. From Cervantes to Mishima, Pepys to Turgenev, Irma had stripped them all of their original covers and jackets and rebound them in a wild spectrum of shades and materials. Philip is certain that somewhere within them is the secret to her disappearance.

When the 351 books arrive, Philip shelves them alphabetically but approaches them “using a 3, 4, 7 sampling… This, he often explained to Irma, was one of the simplest and most effective formulae for achieving a representative sample of any finite collection” (p. 20). His method leads him first to Borges’s Ficciones, and Philip—dazzled by the stories—wonders why Irma never urged him to read any of her beloved books before. As one book leads to another, he begins to suspect that Irma intends for him to discover more than her favorite literature.

Restless after an evening of reading, Philip wanders into a nightclub and meets Lucia, a woman who could be Irma’s double. Their encounter is brief but soon he stumbles upon fictional characters that uncannily resemble Lucia. Was his meeting with her pure chance? The mathematician in him dismisses the possibility and soon realizes that Irma—anticipating the order in which he would read them—has planted a series of teasing messages within the texts. Each is more impossibly subtle than the last and Philip realizes that he does not truly know where the authors’ words leave off and Irma’s begin.

He begins applying mathematical equations to the events unfolding around him and catches sight of additional clues strewn throughout his own life. His ex-wife Beatrice reveals Irma’s role in their troubled marriage. His stepdaughter, Nicole, has recently renewed contact with an urgency that conveys the crisis she is undergoing. Meanwhile, Nicole’s brother, Sam, has also disappeared, and Philip senses Irma’s influence at play. Don Quixote leads Philip to Spain, where he begins to wonder just how much power Irma has in the narrative that’s become his life.

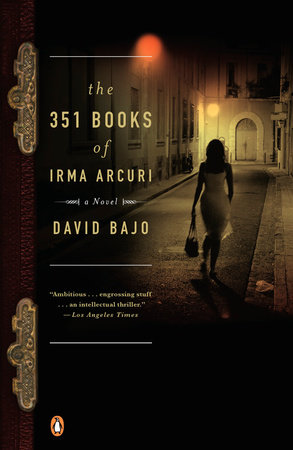

Like The Shadow of the Wind, The 351 Books of Irma Arcuri is an enthralling tale about the power of literature, and Irma herself is an intelligent and brazenly sexy heroine who imbues David Bajo’s unforgettable debut novel with intensity and intrigue.

ABOUT DAVID BAJO

David Bajo grew up the tenth of fifteen children on a California ranch overlooking the Pacific and the Tijuana bullring. He earned a master’s in English literature at the University of Michigan and received an MFA in fiction from UC-Irvine. He worked as a journalist in San Diego, covering border culture, Mexican wrestler movies, music, and drama. He also translated Spanish and Portuguese sociology, anthropology, and physics. David has taught writing at UC-Irvine and Boise State, and presently teaches at the University of South Carolina. He’s published stories in The Sun, Zyzzyva, and The Cimarron Review.

A CONVERSATION WITH DAVID BAJO

Q. Philip is on a quest perhaps as illusory as Don Quixote’s and Irma is certainly his Dulcinea but—from another perspective—she could be seen as Bachelor Sansón Carrasco. Similarly, Irma appears to be a combination of Conchis and the twins from The Magus. What books did you have in mind when you began your novel? Were there any books not mentioned that had a significant influence?

My delusion while writing the first draft was to physically embed it, quires at a time, in a decaying copy of the Quixote, to begin answering the first question. This will sound impossible, but I didn’t consciously consider as influence The Magus—until it came time three quarters into the story to pull a book from Irma’s shelf for Sam. And only after I chose it—randomly, I thought—did I realize that I first read Fowles’s novel when I was Sam’s age, seventeen. I used it to smuggle Valley of the Dolls in a book sandwich with The Master and Margarita. The two outside books in the sandwich cover for the book in the middle, which is the one you really want to read, in this case the Jacqueline Susann. But I read The Magus first, all the way through, swept in by the Grecian islands. Kept stopping in the middle of Dolls to go back and read The Magus. The Fowles was far sexier than the Susann. So was the Bulgakov, but in a different way, more with the visceral quality of the language. The words felt sensorial to me, made me want to drink apricot juice and read The Magus. Which I did.

Another book not mentioned? Yes. Anna Karenina. When I was a college senior, I had a friend who told me she was falling in love. She was out of my league, considerably out of my league, so I knew it wasn’t with me. She was two years older, engaged, beautiful. I would look at her face during our Milton seminar and sometimes she’d catch me and I would smile as though I were just trying to share a joke or thought, then look away like a schoolboy. She was from Germany, dark, and I found her extremely exotic. She’d wear dresses she purchased from different cities around the world. We’d have drinks together at the Silver Spigot and talk about literature, always getting back to our ongoing and unresolved argument about Turgenev vs. Tolstoy. I was Turgenev and she was Tolstoy.

Sometimes she’d take me back to her place, where she lived with her fiancé. She would only do this if he was there. I liked him. He was amazing, wore a white armband of protest on his graduation robe, and got on the news. Going back to her place was all very innocent. One evening at the Silver Spigot she told me she just wanted to read with someone, the way people used to read together.

When we went back to her place, we were alone. She lit a fire. She had a fireplace. In college, who has a fireplace? She handed me a drink, sat me down across from her, and read to me from Anna Karenina. It was that whole elliptical passage leading up to Anna’s death, when Tolstoy takes you deep into her thoughts and emotions. It almost transforms into a first-person narrative. And in the final image beneath the train wheels he bathes her imagination in the light of a reading candle. It’s that same candlelight Quixote read by, that we all read by, to go mad, isn’t it?

There she was, reading to me in this soft continental accent, her lips moving in firelight. For the next two weeks, leading up to graduation, I walked around with his yellow halo cinched around my vision, slightly vertiginous. I thought something had gone wrong with my eyes.

Q. The multiplicity of identity seems to be a pervasive theme of your novel. Was this influenced by either the fact that you grew up in a border town or because you come from an unusually large family?

Yes and yes. I lived on both ends of the kaleidoscope. My vision of others was always a tumble of fragments forming endless, intricate patterns. My sense of self was also that tumble of fragments, in moments that locked in an intricate, irretrievable pattern, then tumbled forward. Tijuana is a living kaleidoscope. And I could see it at night all aglitter from out my boyhood bedroom window. Through the other window lay the view of San Diego. I lived in both worlds at the same time with fourteen other siblings experiencing the same duality, but in fourteen different ways. We traipsed between the two. Our dad took us to explore all parts of Tijuana, from the very poor Third World sections to the very exclusive ones. He was a physician on the border and most of his patients came from these disparate parts of that crazy city. He volunteered at an orphanage there—still does, actually—and would take us. He took us on Tijuana house calls, big groups of us. We’d go from walking up tire staircases in cliffs to walking up tile ones in beachside mansions.

We rode around the Otay and Tijuana mesas. At first we actually had a big green school bus, kind of like the Partridge Family but without the singing. We traded that in for this thing called a Travelodge. Imagine a huge liver-colored jellybean with wheels. Sometimes all seventeen of us—parents plus kids—would be compressed into that thing, crossing the border into Tecate for the feria there. In that situation, jammed together in a very conspicuous Travelodge rolling into a different but twin culture, you simultaneously protect your identity and release it.

Q. A fiction writer, teacher, and, no doubt, a lover of literature yourself, why did you choose to make your protagonist a mathematician who has never read much?

I wanted the story to work for readers more experienced than myself and less experienced than myself. If you’re an experienced reader, you’re ahead of Philip as he steps into Irma’s specialized library and premeditations. But you have to stay with his formula, follow the swing of the pendulum. You might know what’s coming, but you can’t help him, warn him, yet hopefully you stay with him out of kindness, and out of fascination with his odd mathematics, out of admission of our own odd formulae for understanding what we read, what we live.

I translated a textbook on materials science once, the same one Lucia is translating in the novel. Going into the book, I didn’t even know what materials science meant, what the hell vibrating lattices were. Whenever I got to the math, which was often, of course, I would just leave blank space for my editor to fill. He was a physics PhD. It felt strange, writing that way, leaping over these chasms in the text, trusting an entirely different construct and conscience to make sense of it all. Only in unison could we reconstruct the book. That’s kind of how Philip and Lucia navigate Irma’s contrail, I suppose.

Q. Are you, in a sense, pitting rational thought versus psychoanalytic thought? Philip versus Irma?

Irma controls the book from the outset, in varying degrees. The analogies are endless. Philip is the moth squirming in the chrysalis, Theseus in the labyrinth with the string Ariadne gives him, the second theme that keeps working its way to the surface of the sonata, the blurry photos in a Sebald novel that affect the text.

Mathematical thought isn’t any more rational than psychoanalytical thought, or more rational than normal quotidian thought. It’s just as interpretive as any highly evolved language, gets you muddled, into trouble even, if you don’t allow it flux. I did see this story as Philip versus Irma, but neither of them stands for any thought form.

Q. Irma tells Philip that in Pepys, “at table” or eating is veiled code for sex. Is there a similar code at work in your novel? Is sex just sex or does it stand in for something else?

For Irma, Lucia, and Philip, sex is a comprehensive expression, a physical, emotional, even aesthetic exploration of another who is game but elusive. In the novel, I don’t see sex as a code for something else, or as standing in for something else. Lucia, maybe because she is the translator and the one most willing to admit her body and her emotions, is the one who claims that she, Philip, and Irma are of a kind rare in the world. With sex they can explore that about themselves and each other which exists beyond language, beyond thought that can be put to language. Sometimes, when you want to understand a person who is similarly inclined, you start there. Sometimes you end there.

Language and text are very important and powerful to all three of them. So sex, which can take them beyond even language’s formidable power, becomes crucial in making themselves known to one another. They need to get to that point of exchange where they lose their voices.

I really did want to explore that kind of good and game sex, faced it with much trepidation. Often the fiction writer’s good, effective tack is to make sex essential to the story awkward, or understated, or even fearful. Ian McEwan does that so well. But what if it isn’t awkward or fearful? What if it can’t be understated? What if the people involved know what they’re doing, and like it, and are good at it, yet still wonder where it might carry them? Beatrice, Philip’s first wife, knows exactly what she wants and exactly what to do. She’s ahead of them all in that regard, even Irma. All four of those characters take sex very seriously, not lightly or casually at all, even when it’s spontaneous.

Q. It’s clear from your description of Peter’s childhood that he lacks the emotional sensibilities that spark the creation of music or literature, yet he is an appreciative audience. Are you suggesting that the best readers are those without the desire to craft fiction themselves? Who is your novel’s ideal reader?

I do suggest that, but do believe that someone with the desire to craft fiction can read with that desire suppressed, or with that desire unguarded. And I believe that a magnificent book can overcome or redirect that desire in the fiction writer and render him a pure reader. Readers are more important to fiction than writers. They determine what endures, what survives the silverfish; they build the metaphorical library of Alexandria, its labyrinth. It’s what Borges pursues in Ficciones, what he illuminates in “The Library of Babel,” a piece that could only be composed by the director of the National Library of Argentina who is going blind.

My novel’s ideal reader is anyone who would be willing to get lost in the labyrinth of Borges’s Library of Babel, or Eco’s library in The Name of the Rose. Lucia invites Philip to come get lost in the labyrinth with her, and he meets her there physically, emotionally, psychologically, readerly. The novel’s ideal reader is anyone who would, no questions asked, go meet Lucia in the darkness of Ionic Street, Quixote in hand.

Q. Irma once tells Philip, “You don’t write a book because you have to. You don’t write a book because you have something to say. You don’t write a book because you have a story to tell, a story that must be told. You write a book because you need to bind it and watch it come unbound. That’s the only decent, honest reason” (p. 194). Why are you a novelist? Why did you write this book?

I wrote Philip’s question in the first draft, putting it right where it had to be in the story. For the story to make sense, he had to ask it and she had to answer it, both dropping all pretense. Irma’s answer, which I didn’t find until a later draft, is the truth of the book. I wrote this book because I needed to bind it and watch it come unbound. I need to find it one day, when I’m very old, in some strange attic where it will be decomposing, feasted on by the Chaetomium that is eating the library Philip searches in Corsica. It will have lots of penciled margin notes, misplaced and missing pages, and dog ears. And I’ll be able to read it learning the story anew.

When Irma says that, she’s submitting herself to the collective process of binding a book, and the collective process that decomposes a book, beginning with the acid on a reader’s fingers and including the silverfish and fungi that will bore holes through the spine and paper. Most of that process is beyond her powers, occurs according to the whim, appetite, and wonder of others. You spin forth a novel and then watch it become something else; it’s thrilling, frightening, never closed.

Q. You, like Lucia, have worked as a translator of Spanish and Portuguese textbooks. What are some of the most interesting ideas you’ve come across in your translating work? How does being multilingual inform your work as a novelist?

Aside from a couple of hard-science textbooks, most of what I translated was social science, a combination of ethnographies, quantitative studies, and lots of theory. It was factory work, for twelve bucks an hour. I would do forty articles a week. It was all highly interesting and educational, but it was like standing under a waterfall of ideas. For seven years. But it was a good day job for a writer and it allowed me to travel and to telecommute from wherever I wanted to be. Like Lucia in the novel, except in much cheaper hotels.

Being able to consider how a phrase might be written, a thought expressed, an image rendered, in another language is highly valuable to a writer, especially when you’re dissatisfied with what your English has accomplished on the page. Every language reaches some area of human expression unique to that language, stands alone on a frontier. Another language enables you to turn a thought under different light.

W. G. Sebald’s process fascinates me, the way he first writes his novels in German, has Michael Hulse translate them into English, then revises them himself in English. He masters both languages, yet chooses to refract his work using both equally, like someone firing a brilliant beam of light through three carefully aligned lenses, one German, two English. What he produces is utterly unique.

Q. As a journalist, you covered Mexican wrestler movies—an essentially “low” culture spectacle—but, as a novelist, you’ve written an intelligent, high-culture literary work. What are the correlations between these interests?

My managing editor at The San Diego Review had me cover border culture, all genres of it, genres I didn’t even know existed. I covered LA’s Culture Clash performing El Santo vs. The Martians. It was one of the most entertaining and brilliant pieces of political and cultural commentary I’ve ever witnessed, and I can’t even say what I’d call it. Growing up on the border, I had become very familiar with the luchadores and their movies. But Culture Clash invented something new and spontaneous by mixing the wrestling movie with live action and wandering through the audience. In fact, there was no telling who were the audience and who were the performers—because some audience members wore masks to honor El Santo and The Blue Demon. And there seemed to be no separation between what was real life and what was performance. I’m trying to write about that experience now, in a novel. So much for intelligent, high-culture literary work. That answers the question, if you think about it.

Q. Does teaching others to write make writing yourself easier or more difficult?

It makes it more challenging, which is good. I try to present myself as more river guide than teacher. I try to tell students what baggage to leave behind, what won’t fit, knowing they’ll smuggle some things anyway. I lead them upriver. Some pools I know have piranha in them, some hide waterfalls. But most currents we explore together, eyes opened to everything. Sometimes they see things first, before I show them, or before I even see them. Those are the best moments on the river, in the classroom. I am constantly reminded about how much I have to learn. It makes my writing better, I can tell, because now I feel I write more with a sense of informed exploration more than a sense of knowing. And I exchange that with my students. Also, I can say for a fact that there are some amazing young writers on their way to creating new works of fiction, ready to keep Borges’s library alive.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS