READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

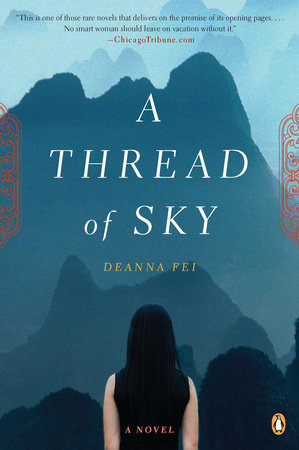

When her husband of thirty years is killed in a devastating accident, Irene Shen and her three daughters are set adrift. Nora, the eldest, retreats into her high-powered New York job and a troubled relationship. Kay, the headstrong middle child, escapes to China to learn the language and heritage of her parents. Sophie, the sensitive and artistic youngest, is trapped at home until college, increasingly estranged from her family—and herself. Terrified of being left alone with her grief, Irene plans a tour of mainland China’s must-sees, reuniting three generations of women—her three daughters, her distant poet sister, and her formidable eighty-year-old mother—in a desperate attempt to heal her fractured family.

If only it were so easy. Each woman arrives bearing secrets big and small, and as they travel—visiting untouched sections of the Great Wall and the seedy bars of Shanghai, the beautiful ancient temples and cold, modern shopping emporiums—they begin to wonder if they will ever find the China they seek, the one their family fled long ago.

Over days and miles, they slowly find their way toward a new understanding of themselves, of one another, and of the vast complexity of their homeland, only to have their new bonds tested as never before when the darkest, most carefully guarded secret of all tumbles to the surface and threatens to tear their family apart forever.

ABOUT DEANNA FEI

Deanna Fei was born in Flushing, New York, and has lived in Beijing and Shanghai. A graduate of Amherst College and the Iowa Writers’ workshop, she has received a Fulbright grant, a New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship, and a Chinese cultural scholarship, among other awards. She currently lives in Brooklyn, New York.

A CONVERSATION WITH DEANNA FEI

Q. In the acknowledgments section, you mentioned your own trip with the women in your family. What were some experiences you had in China? How did they inform and inspire A Thread of Sky?

Ten years ago, I toured China with my mother, my sisters, my aunt, and my grandmother. Even at the time, I was struck by the dramatic possibilities of that journey: the conflicts among six strong, complicated women; the secrets lurking behind a family reunion; the paradox of seeing the country where one is supposed to be “from” on a guided package tour. For me, the tour was the culmination of a year filled with paradoxes, during which I’d studied Chinese in Beijing on a scholarship awarded by the Chinese government—the regime that my parents’ families had fled. I’d arrived with grand plans of mastering my mother tongue, of reclaiming my heritage, and yet I often felt like the more I learned, the less I understood.

After I returned home to New York, I started scribbling some notes, and the characters began taking on lives of their own, completely apart from their real-life counterparts. I realized that I had the seed for a novel. But I was twenty-three and teaching at a middle school in Harlem, and writing a novel seemed like such a far-off enterprise.

A few years later, I was a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and when I had the chance to take a novel-writing class with Elizabeth McCracken, there was no doubt in my mind what story I would try to tell. I hammered out a few chapters, but by then, the setting felt too distant. So I applied for a Fulbright Grant to move back to China to research and write my novel, and I was lucky enough to get it.

This time, I arrived with no classmates or coworkers or relatives or friends—in other words, with my characters as my main companions. I immersed myself in modern life in Shanghai while making periodic trips to the cities on my characters’ itinerary, viewing the sights through their eyes, carrying their histories and personalities everywhere I went. But even my daily life became my inspiration, whether I was riding the bus, ordering breakfast, hanging my laundry out on bamboo poles, or going to a gallery opening.

My time in China eventually stretched to four years. I couldn’t leave, because I had found the heart of the story: the yearning to reconnect. In various ways, each of my characters had become estranged from one another, husbands, careers, family history, even themselves. And separated as I was from my own loved ones, I often felt like I was on that journey alongside them as we lived out the strange truth that, so often, it’s only when we travel to a distant place that we rediscover the meaning of home. To quote Irene, the mother in A Thread of Sky: “Jia—family, house, home. In Chinese, it was all one word” (p. 12).

Q. How did you go about researching the historical pieces of the book?

My primary task was exploring the ways in which my characters are haunted by personal and political histories that come to light during this tour of their ancestral home. Chinese history is so long and fascinating that I sometimes thought my research would never feel complete, but I also knew that my characters and their journeys had to dictate my research—not the other way around.

For example, Kay’s background as an activist led me to the long and often obscured histories of Chinese Americans chronicled by Iris Chang and Peter Kwong, among others. Lin Yulan’s tumultuous past led me to research village life in feudal China, the Nationalist movement during the Japanese occupation, the Communist revolution, and the struggles of exiles in Taiwan. I read historical accounts, conducted interviews, watched movies—and cajoled my own grandmother to write some of her life history in the form of letters to me.

Finally, a common theme running through all six characters’ stories in A Thread of Sky is what it means to be a strong female, what it means to leave a legacy. With that as my guide, I researched the history of feminism in China through biographies of the heroines Hua Mulan and Qiu Jin, as well as contemporary portraits of female leaders such as those in Wang Zheng’s Women in the Chinese Enlightenment and Xie Bingying’s A Woman Soldier’s Own Story.

Q. There is a growing appetite for writing on China. Is there anything that you think fiction about China offers readers that nonfiction or academic writing does not?

I’ve relied on plenty of wonderful nonfiction and academic writing to deepen my own understanding of China, but fiction definitely has its place. China often tempts Westerners to make sweeping, oversimplified statements—for instance, Chinese culture is repressive, or materialistic, or all about saving face. Sometimes this happens precisely because China is a place of such vastness and complexity that it’s easier to make such statements than to convey true understanding; sometimes it’s plain ignorance. Either way, when you combine this impulse with the fact that nonfiction and academic writing are often aimed at arriving at a definitive answer, at some inarguable conclusion, there’s a lot of potential for misunderstanding.

Fiction, by contrast, is aimed at exploration, not explanation. It’s the province of nuance and contradiction. A good novel gives a sense of expansion, of a broadening and deepening view, but it also acknowledges that some things remain beyond our grasp. In this way, fiction can sometimes offer readers a truer perspective of China than other forms of writing.

That, at least, is my hope.

Q. Your female characters react virulently to exoticized stereotypes of Asian women. Do you think Asian American women in general still feel and react in the same way? You mention in a Huffington Post article that women should “pick their battles.” What kinds of guidelines would you recommend?

I think it’s completely up to the individual. My characters probably react more than most because they’ve been raised in a family tradition of female activism, as was I. Of course, there’s no shortage of stimuli to raise the hackles of those of us attuned to how subtle and pernicious the stereotypes can be, and I’m a believer in raising the consciousness of others when we have the chance. But I also think it’s important to keep some perspective—and a sense of humor. Actually, one of my readers said it best. At a reading in Seattle, one woman told me how deeply A Thread of Sky spoke to her because it captures how “we get so used to fighting for everything that we don’t know when to stop.” I think this applies to all women who feel the need to prove their strength day after day at work and at home. Sometimes you have to fight—but sometimes you have to just be.

Q. Upon completing your novel, was there anything that surprised you?

When I first started writing, I assumed that the American-born daughters in A Thread of Sky would be the closest to me, since their personal histories are obviously more akin to my own. But over the years, I became so immersed in the stories of their mother and their grandmother that, often, those were the voices that came to me most easily. Overall, I’d say each of the six women are equally me and equally characters outside of me.

Q. Who are some of the writers you most admire? What are some books that you turn to again and again?

This question always makes me anxious about the great writers I’m forgetting to mention, but here goes. I love to read virtually anything by Alice Munro, John Cheever, Anton Chekhov, Graham Greene, and Edith Wharton. Some of the books that I’ve turned to repeatedly in recent years are Drown by Junot Diaz, The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston, The Transit of Venus by Shirley Hazzard, The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich, Like Life by Lorrie Moore, Bad Behavior by Mary Gaitskill, and Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson. Finally, the book that I always keep by my desk (along with a thesaurus) is Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life. Whenever I start despairing, it revives me.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS