Author Q&A

When did you start thinking you would be a writer?

I always knew that I would be a writer. Well, at least since the second grade. I went to one of these progressive schools where one was encouraged to write stories all the time and they didn’t really correct your spelling. I remember that I spelled yellow with three Ls well into fifth or sixth grade because they kept saying, “That’s great. That’s even more yelllow than yellow.” So I think I was encouraged to be a storyteller from early on. Also, both of my parents are visual artists so I was always around the creative process. It was okay to be creative in our house. Growing up, I thought everyone was an artist with a studio in the house. I remember once I was having a sleepover at a friend’s house and his father left for work in the morning and I thought his father was leaving forever. I had no conception of what a normal 9 to 5 job was.

Did anything change when you got older?

Well, even though I knew I was meant to be a writer, I steered around it in some ways. It was very difficult for me to say “I am a writer.” When I went to college, I started getting involved in teaching, and giving back to the world started to become very important to me. For some reason, I saw writing as this very self-centered pursuit that wasn’t in that same vein of social justice, so I struggled with that, grappling with these two sides of me. How do I combine my compulsion to teach and my evident natural propensity for storytelling? I graduated from Brown with a teaching degree and started down the path of teaching and also doing educational research, but in my mid-twenties I had that quarter-life crisis where I asked myself, “What am I doing? I need to give writing a chance.” So I enrolled in the MFA program at Columbia and managed to stretch that out for four years…which allowed me to write this book.

You grew up in Cambridge, went to school at Brown and Columbia, why set the book in Montana?

I was conceptually interested in the West, and cowboys, and why we’re obsessed with cowboys, and with landscapes, and with what “the frontier” culturally represents for us. And with this book I knew I wanted to write about the son of a cowboy. Originally, when I looked at my prewriting for the book and some of my false starts, T.S. Spivet was a 57-year-old drunk in a Parisian prison looking back on his life on the range. Thank God I didn’t follow that. So I rethought it and decided, “No, T.S. isn’t drunk, he’s twelve and he’s hyper-analytical and obsessed with commenting and drawing and diagramming everything.”

So how did you choose Butte and Divide, MT as your location?

I’m not really sure where most of the details or choices in my writing come from, but I can tell you that I’ve been fascinated with Butte for awhile. About 10 years ago, on my way from San Francisco to do an improv performance in Saskatoon, I stopped with some friends in Butte and had lunch at the M&M, a bar that for many years actually had no lock on the door because it was open twenty-four hours a day. There are a lot of bars in Butte; it could give any town a run for its money in this respect. Anyways, soon we were wrapped up in several long stories with some locals about Evel Knievel, the hometown hero and the Berkeley mining pit, which we had just passed on our way to the downtown. Something got stuck in my head that day and never left. Butte and its once mighty Copper industry seem so desperately emblematic of the boom and bust and beauty and tragedy that is all wrapped up in the West.

And Divide? Well, I wanted to write about a ranch, so I knew it had to be just outside Butte. I’m also very interested in the symbolism of the continental divide, that invisible boundary that can also represent the emotional divide in the family. I was driving down I-15 one day and saw this mileage sign that said: "Divide 1, Wisdom 52" and I knew this was the place. "It takes place here," I thought. I’ve since met a few people who actually live in the spot where the Coppertop ranch supposedly stands—and I was nervous to meet them, because what if I got it wrong, you know? But they were very gracious, and excited that I had written about their town. One of them even had me sign her phone book “in case I became famous.”

You traveled a lot researching for the book?

Yes. I visited Butte a bunch of times, pouring over the incredible archives there, much as T.S. does in the book. At the height of its boom in the 1920s, Butte had seven daily newspapers, so there’s a lot of material to work through.

At some point I also decided that I should become a ranch hand on a western ranch so that I could really experience what it was like. After thinking about this prospect for only a couple of minutes, however, I realized that I would probably be more of a liability on the ranch than anything. So I thought about what skills I could actually offer, and they weren’t much, but I one thing I can do is teach creative writing. I wrote a couple of dude ranches, offering to teach a writing workshop on their ranch, and one ranch wrote back and said, “Sounds great! What’s a writing workshop?” Somehow I got six people from around the country to come to this amazingly beautiful working cattle ranch in the Idaho Tetons and for a week we had this transcendent experience. We would workshop intensively in the mornings and then ride the range in the afternoons, and this worked out really well because it’s almost impossible to hold onto anger or tension when you’re on horseback; any worries you might’ve had about a particular story or insecurity or divorce, just drift away into the high country. We also participated in a real round-up, which was sensational. When you’re working on horseback, the distance between you and the animal disappears. By some coincidence, the workshop was all women (except me, of course) and these women really got into the branding and castrating of the calves. I had to look the other way, but they were right up in it.

You did comedy improv at one point during college – did you find that it helped writing the novel?

If you give me a script and I’m on stage, I’ll freeze up because I think I’m going to say it wrong. But with improv I always felt so free. I was never nervous because there’s no wrong answer. My brain works like, “Oh, you say that and I say this and we’ll enter this wormhole together and follow this until we can’t follow it any more.” I love creating a world and then pushing the boundaries of that world. I write like I improv: I’ll write something on the page and be completely surprised by it, and then I’ll follow that little tiny thread to the end. With writing a novel, you can follow those threads and see where they take you; particularly with this book, where it was all about the voice of my main character.

How did you create the marginalia that appears in your book?

I started with footnotes. I wrote the whole thing at first without doing any illustrations because I wanted to get the writing right. Footnotes are so problematic in fiction and have such a tangled history. There’s something sort of pompous about them. And they’re an intentional break of the reading process, which is very evasive and annoying (particularly endnotes). It really disrupts everything and whenever I read things with footnotes, fiction or nonfiction, I tend to read a couple lines of them and end up choosing to skip them. So my question was, “What if the most important parts were in these digressions, in this satellite material?” And somewhere along the line, when I started thinking about the page like a map itself, that’s when I thought maybe they shouldn’t be footnotes, but they should be marginalia where you’re physically directed to them, where your hand is held and you’re led to them through arrows and such.

What did you draw upon for inspiration for the character of T.S.? Were you an analytical child?

I’ve had people ask me if I’m as obsessive as T.S., if I map everything and keep a notebook. Well, I was very into maps as a kid. I spent a lot of time with the National Geographic Atlas, pouring over these maps of distant places, looking through the index of all these exotic names. I think a map is like a good story in that it gives us just enough to sink our teeth into but also leaves enough room for us to fill in the gaps with our own memories and stories. I’d make up crazy stories about Uzbekistan and what went on there and create these from one Island to another. In seventh grade one of the tasks they gave us was to draw the world by memory, which some people dreaded but I really got into. I can still sketch a world map fairly accurately. There’s a character in the book, Corlis Benefideo, borrowed from a Barry Lopez short story, who says that we’ve lost touch with really knowing the place that we’re from and this is probably true in the world of GPS systems.

As for other things I have in common with T.S., I do archive the world to a certain extent in notebooks and on my “writing board,” but maybe not as much as I would like to. I have a fantasy where I have a room completely filled with notebooks from top to bottom—my own personal Akashic record of existence. But the truth is probably a lot less glamorous. I’ve always loved diagrams and the incompleteness of diagrams. For instance, there’s something so satisfying when you look at those airplane safety manuals. I love their simplicity: here’s how you put on a child’s oxygen mask. As if all you have do is follow these instructions and life will be fine. But then you realize that’s not how the world works. That’s why we keep coming back to diagrams—because we wish we could follow a step-by-step program for how to fall in love or to live a moral life. So I love the idea of a kid trying to understand the world in all of its horrific complexity by simply mapping it out. And it seems like growing up is transferring the unknown to the mapped, for better or worse. I had an art teacher who said that he spends most of his time trying to get his students to see like kids again, since we replace what we see with an intense system of symbols. It’s interesting to give a kid—who’s still largely in this pre-pubescent state of seeing the world sans symbols—this amazing set of coding and mapping skills and see what comes out of it.

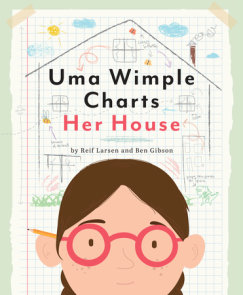

Are all the illustrations in the book drawn by you?

Everything’s drawn by me. My publisher paired me up with a designer, Ben Gibson, and that was great. He helped to push the drawings to the next level in terms of giving them a lot of amazing texture and he really listened to what the drawings wanted to be. The final edition is going to have this amazing Moby-Dick spread at the end that goes across eight pages. I would have loved to have done that but there’s no way I could have approached it. T.S. is obsessed with mapping the real world, but every time he tries to map the fictional world all his powers break down. Because the novel is infinite and everything is possible. And the Moby-Dick map is amazing because you start to see his madness around page three and then it devolves into this kind of fever dream of infinitum.

Have you thought about how people will react to the illustrations – mixing art with text?

I definitely didn’t set out with the idea to write a novel with images. People might say this book is “unconventional,” but I think I’m pretty old-fashioned. In my MFA program, there were a lot of people doing very non-narrative, avant-garde writing and I wasn’t one of them. I believe in character and plot, and sometimes plot is a four letter word in the MFA program; I actually really believe in giving these things to the reader. I think story and character are what gets those tenterhooks into the reader’s being. Every choice in this book was driven by wondering how can I explore this character and express him on the page. In that way it’s a very traditional novel, more so than a lot of novels coming out now.

How does it feel to move from “struggling writer” to “Writer” with a capital letter W?

There were certain points when I was writing this novel where it seemed all I was doing was writing a 300-page bedtime story. And why would anybody want to read this? But I’ve realized this, and it may sound stupid, but I’ve realized that releasing a story to the world is an act of giving. I’ve changed in how I think of writing. In its most basic form, literature is a giant conversation between readers and writers. When you read a book, it punctures your world for ten minutes, twenty minutes, two weeks; it pushes you off your orbit just enough so we get that literary chill, when your knee deep in a book and can’t wait to get back. I think that’s why we read. I no longer think of writing is as self-centered a pursuit as I once did. That said, I’m still very excited to be a teacher. I’m going to be a teacher for the rest of my life. I know this. Some writers dread teaching and just teach to pay the bills, but for me, at least, the challenge of getting the students to open their eyes or nudge them is actually quite close to the discovery on the page. The discoveries that happen in the classroom are similar to the discoveries that you can make about a character. It informs my writing as opposed to taking away from it.

Your novel has sold in 22 countries around the world – do you find that surprising since on the surface it seems like such an American story?

Well, this was actually a huge surprise to me, because you’re right, this is quite an American story, really, almost like a traditional Western—boy on ranch, boy goes on cross-country journey, boy finds answers. I wasn’t sure it would really translate across the pond. But in talking to people, I’ve come to realize that the notion of the “frontier” is a nearly universal symbol, that there’s a kind of longing there—for brighter pastures, for a better time, for the end to our hardships—and it’s a longing that many people can relate to. I was listening to a radio program about how Dolly Parton can fill stadiums in Zimbabwe and around the world, and many of her audience members don’t speak English, but they get the feeling behind her songs, the “My husband left me and now I’m broke” pathos. And also: a story is a story is a story. If something rings true to itself, it’s going to translate. But, yes I was really surprised. I’ve been working very closely with all the translators. We’ve set up a blog where I answer their crazy questions about how to translate all this cowboy-speak.

You taught in Africa, what was that experience like?

I went to South Africa because I was really fascinated with the transition from apartheid to black democratic rule. It was a relatively bloodless transition, compared to the civil war that could’ve been and the new government seemed to put a huge emphasis on education as the way forwards. So I took some time off from Brown to teach at this school in Cape Town. I taught English and Drama and I also became one of the school counselors. I came in armed with all of these very progressive teaching ideas from Brown; I thought we’d do all kinds of experiential learning and set up all of these learning goals and I got burned in a matter of months. Very quickly it became, “How do we get these kids to show up to school?” That was the number one problem. My only achievement at that school was that I introduced a Student of the Week award. In the U.S., I totally cringe at those obnoxious “My Child is an Honor Student” bumper stickers, but in the faculty room in this school, all the conversation was so negative about students. It was like, “That guy deserves to be in jail. I don’t even know what he’s doing in school.” So this award was just trying to introduce positive discourse—any positive discourse—among the faculty. And there were some weeks where they were like, “No one deserves an award.” It was tough.

But just as I was getting burnt out there, one of the teachers told me I had to see this other school. “It’s up in Botswana. Before you leave Africa go to this school. It’s the future of the continent.” It’s this school called Maru-a-pula, which means “Clouds of Rain.” Rain in Botswana is a blessing so it also means “Blessings of joy.” This school is in the middle of the bush, with desert all around, and it’s filled with these amazingly motivated students. These kids work their butts off. They take their A-levels, they’re doing all this community service, arts, athletics and more and then they go off to these U.K. colleges and Ivy League schools here. And most of these super confident, motivated students are women. The future of Africa lies in its women.

You worked with a marimba band in Botswana. Will you explain?

One day I was walking past the music room and I heard this amazing music… it was the school marimba band. A Zimbabwean marimba is like a giant wooden xylophone, with these African gourds beneath the keys. There were ten of them, played by these students, and it was the most amazing sounds I’d ever heard. I knew right then that I had to bring them to the U.S., so when I got back to Brown the next year I spent most of my senior year organizing this marimba tour, where the band visited schools up and down the east coast. It was awesome, but it was a lot of work. For years after that the school was like “Why don’t you organize another tour?” And I said “no way,” and then I finally last year I agreed to do it again.

This second tour had grander ambitions–Maru-a-Pula had since started an AIDS orphan scholarship fund, and in addition to playing schools and universities we also planned several large fundraisers for the scholarship fund. Anyways, the organization of the tour was another six months of hellish, unpaid work and then the day before they were to arrive I got a call from the principal of the school, who was at the Johannesburg airport with the band. He said that baggage regulations had changed and they couldn’t bring the marimbas on the plane―could I please find 10 Zimbabwean C Major (F# added) marimbas by tomorrow? Needless to say, I went into a kind of fever, and was on the phone for six hours with marimba players all over the country, trying to track down 10 Zimbabwean marimbas. I talked with every member of the marimba community in the U.S. from Spokane to Santa Cruz, Santa Fe to Asheville including the lead marimbaist from the "Lion King" on Broadway. After six hours, I had only discovered this: finding the particular Zimbabwean C Major (added F#) marimba in this country (let alone an ensemble of 10) was nearly impossible.

Then a minor miracle happened. I received a call from a Martha Jenks from Syracuse, New York. Martha and some of her friends had attended a Zimbabwean music workshop several years ago led by Alport (the director of the Maru-a-Pula marimba band and a legend in Zimbabwean Marimba music). They were so inspired by the music and the traditions that over the course of the next couple of years they built their own set of Zimbabwean C Major (added F#) marimbas out of wood, replacing the African gourds with PVC piping. On the phone, Martha was a bit nervous that her marimbas would be properly taken care of, but she said it would be an honor for Alport’s band to play them.

But we were one short… until another miracle happened. NY1, the local news station in New York, had caught wind of the marimba crisis and broadcasted a cry for help on their station: could any New Yorkers lend a hand to this marimba band en-route to the states? I thought this was kind of amazing: New Yorkers searching their basements for that spare Zimbabwean C Major (added F#) marimba beneath the unused kayak. But New York is an incredible city: a woman from Queens actually had a spare soprano Zimbabwean marimba that she had bought while living in Santa Fe (which has that vibrant marimba community). It was the missing marimba, and the woman delivered it in time for the first concert. The tour was a great success, and in some ways, restored my faith in humanity. Or maybe I had never lost my faith in the first place.