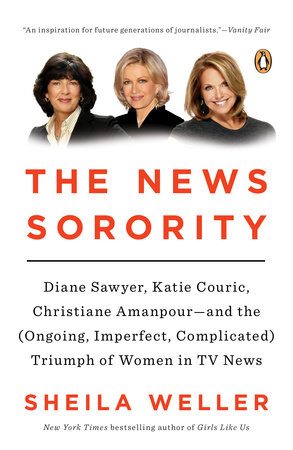

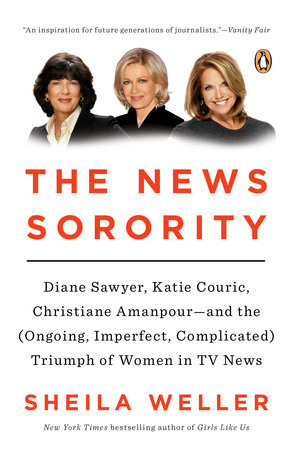

The News Sorority

By Sheila Weller

By Sheila Weller

By Sheila Weller

By Sheila Weller

By Sheila Weller

Read by Morgan Hallett

By Sheila Weller

Read by Morgan Hallett

Category: Biography & Memoir | 20th Century U.S. History

Category: Biography & Memoir | 20th Century U.S. History

Category: Biography & Memoir | 20th Century U.S. History | Audiobooks

-

$24.00

Nov 10, 2015 | ISBN 9780143127772

-

Sep 30, 2014 | ISBN 9780698170032

-

Sep 30, 2014 | ISBN 9780698154568

1037 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Unplugged

Due South

Early Poems

The Art of Crochet Blankets

Garfield Fat Cat 3-Pack #20

Tess of the D’Urbervilles

Garfield Fat Cat 3-Pack #21

The Lady in Gold

Orchard

Praise

New York Daily News :

“This immensely readable book made headlines before publication for its irresistible gossip. It is dishy, but it’s also a close up and very personal examination of three women who broke all the barriers.”

Kera Bolonik, The New York Times Book Review:

“… it’s hard to come away from The News Sorority feeling anything less than admiration, if not reverence, for Couric, Sawyer and Amanpour, and sympathy for all the women… who had to wrangle with ratings, network politics and defiantly sexist executives, while managing the delicate egos of their male counterparts. And that is, in the words of the old CBS slogan, ‘very good news.’”

Los Angeles Times:

“…a well-reported and refreshingly fair-minded biography of these gutsy and influential newswomen. Given the complexity of the subject matter, the remarkable thing is that Weller has produced a book that manages to be both compelling and resolutely evenhanded. Even when the catnip of rivalry raises its hoary head, Weller chooses balance. There are lots of controversies, but they usually come along with opposing opinions from different observers and in a broader context.”

The Washington Post:

“It’s worth reading The News Sorority as both a handbook of cutthroat office politics and a cautionary tale. These women brought ego, ambition and a willingness to play just as rough as the boys to the newsrooms—and made history because of that.”

Chicago Tribune (Liz Smith)

“[D]aring, dashing… Sheila Weller has written “the” book of the year on TV broadcasting, a thing that may be a dying, rapidly changing art form, but it’s definitely still going to need voices and faces and intelligence giving out the news no matter how much our socially gadget-manipulated changing world changes. There will always be stars and TV has had them in spades… This is a terrific book. I marked mine so many times, it is virtually unreadable. Believe me, if you like history and gossip and believe, like I do, that gossip IS history — you will love reading about the big three.”

Vanity Fair:

“Weller rivetingly recounts these gutsy ladies’ time on the front lines of domestic and international war zones, political battlefields, and live morning television; the prejudices they’ve faced; the personal sacrifices made and losses suffered, as well as the backlashes that followed their every gain, fueling their ambition and building their resilience. Weller’s portrait of how these extraordinary women, in the words of Sawyer, turn “pain into purpose” is an inspiration for future generations of journalists.”

New York Daily News

“This immensely readable book made headlines before publication for its irresistible gossip. It is dishy, but it’s also a close up and very personal examination of three women who broke all the barriers in TV news in terms of what it took, where it got them and the price they paid.”

Houston Chronicle:

“Weller is brave to write biographies with more than one primary person at the center. Professional biographers know that such a decision complicates research and writing exponentially. In a previous book, Weller… tackled three female vocalists. That book… deeply touched the emotions of many readers I know, female and male. I suspect The News Sorority will, too. [It’s] a book that makes age-old gender battles seem fresh.”

NYCityWoman.com

“[T]his book is not just the story of the fight against sexism waged by three plucky but different dames. The News Sorority is also a tale about the bygone heyday of network news… Yet it is filled with important truths—Vanity Fair style—about feminism in the news workplace… Weller is terrific in citing genuine and unique strengths: Amanpour’s relentless reporting on the horrors suffered by civilians during the war in Bosnia and the plight of Darfur; Couric’s campaign against the colon cancer that killed her first husband, complete with her on-air colonoscopy; Sawyer’s instinct for inspirational pieces about people like the Chilean miners and her humane yet probing interview with Whitney Houston.”

Bloomberg Businessweek:

“Weller’s book is sure to be catnip to TV obsessives and people in the news business.”

Buffalo News:

“This is an important book.”

Kirkus Reviews:

“As she did in her fluid multitiered biography Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell and Carly Simon—and the Journey of Generation, Weller takes apart feminist icons of her generation—those who came of age in the 1960s and ’70s—to see how they work and how they made it to prime time. Inspiring bios of today’s professional heroines.”

Booklist:

“Best-selling author Weller draws on interviews with their friends and colleagues to offer portraits of the will and ambition each mustered to achieve iconic status. Weller details the personal tragedies they’ve dealt with… [and] also explores the unique personalities of these women and the set expectations among broadcast executives and viewers that they have had to overcome.”

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In