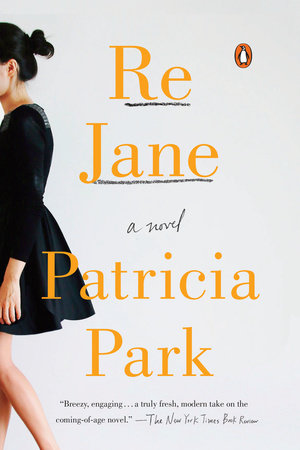

Re Jane

By Patricia Park

By Patricia Park

By Patricia Park

By Patricia Park

By Patricia Park

Read by Diana Bang

By Patricia Park

Read by Diana Bang

-

$17.00

Apr 19, 2016 | ISBN 9780143107941

-

May 05, 2015 | ISBN 9780698170780

-

May 05, 2015 | ISBN 9780698404083

810 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

The Women of Brewster Place

Self Care

The Assistants

State of the Union

The Intermission

New People

The Red Moon

The World in Half

The Shortest Way Home

Praise

“Breezy, engaging… a truly fresh, modern take on the coming-of-age novel”–New York Times Book Review

“Like her Brontean namesake, Jane narrates her tale with honesty and wit. . . Reader, you’ll love her”–O Magazine

“Snappy and memorable with its clever narrator and insights on clashing cultures.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“Be ready to mull over your own place in the world as you root wholeheartedly for Jane to find hers.”–Glamour

“Re Jane . . . drolly explore[s] issues of class, ethnicity and women’s autonomy for an unlikely heroine of the 21st century.”–Maureen Corrigan, NPR

“Park’s debut is a cheeky, clever homage to Jane Eyre with touching meditations on Korean-American identity. . . . Park’s clever one-liners, and her riffs on cultural identity will resonate with any reader who’s ever felt out of place.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Re Jane is breezy and accessible. . . Park offers real insight into assimilationist struggles . . . Park’s portrait of Korean-American life feels authentic and is ultimately endearing. Charlotte Brontë would be proud.”

—BookPage

“Park is a fine writer with an eye for the effects of class and ethnic identity, a sense of humor, and a compassionate view of human weakness. . . An enjoyable book offering a portrait of a young woman struggling to come into her own in the increasingly complicated opening years of a new century.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“[Jane’s] journey ripples with comic and surprisingly authentic moments. Park is a smart, engaging writer, able to capture the emotional weight of a romantic gaze as well as the complicated ties of family. . . . Most everyone who has struggled to fit in will relate to parts of Park’s coming-of-age tale. . . Reader, try not to leave charmed.

—Denver Post

“In her delightful debut novel, Patricia Park uses the classic novel Jane Eyre as a template to examine very modern concepts: questions of identity and love, culture and conscience, even the hardships of immigration. But you don’t really need familiarity with Charlotte Brontë’s most famous work to appreciate Re Jane; it’s entertaining all on its own, vibrant and witty and a hell of a lot of fun.”

—The Miami Herald

“A sensitive, witty tale of the search for belonging….Park’s novel is so much more than a mere retelling of Jane Eyre . . . Readers should feel free to take this ‘Jane’ as is – an astute, resonating, humorous, discerning, original debut.”–The Christian Science Monitor

[A] delightful first novel…Park’s narrative voice is energetic, witty (the book bristles with one-liners) and thoughtful.”—BBC.com

“Re Jane is a rich and engaging novel. Besides being a love story, it is infused with contemporary subject matter, such as longing versus belonging, the immigrant experience. Patricia Park writes with earnestness, honesty, and exuberance, which make the novel thoroughly enjoyable.

—Ha Jin, National Book Award-winning author of War Trash and Waiting

“The Korean Americans of Queens find a daring new voice in Patricia Park’s debut novel, as she takes a story we know and makes it into a story we’ve not seen before–a novel for the country we are still becoming.”

—Alexander Chee, author of The Queen of the Night

“Patricia Park’s Re Jane is packed with authenticity, poignancy and humor. I was enchanted by this modern retelling of Jane Eyre as the tough yet vulnerable narrator captured my heart.”

—Jean Kwok, bestselling author of Girl In Translation and Mambo in Chinatown

“In Re Jane, Patricia Park transforms Charlotte Bronte’s beloved novel with her own inimitable wit and imagination….A wonderfully suspenseful novel that will delight those who know the original, and those who don’t.”

—Margot Livesey, author of The Flight of Gemma Hardy

“A noteworthy debut from a writer who opens a window to an understanding of immigrants anywhere.”

—Elizabeth Nunez, author of Prospero’s Daughter and Anna in-Between.

“Re Jane is a contemporary retelling of Jane Eyre that’s also entirely its own exquisite story. Jane is a hilarious, sometimes muddled, and utterly beguiling heroine. Park’s surprising twists and razor-sharp writing and deep heart make the pages fly by. This story is all about what it’s like being young and learning from mistakes and figuring out who you are without fear.”

—Margaret Dilloway, author of How to Be an American Housewife

“Some nerve, to take Jane Eyre, reconfigure it, make the heroine an orphaned half-white Korean girl, all the while mixing new-fangled Jello shots, hipsterisms, and spicy fish stew with old-fashioned romance. Some nerve to bring it off with such energy, color, and emotional insight! Reader, you’ll love it.”

—Daniel Menaker, author of My Mistake

“What a pleasure, this journey from Queens to Brooklyn to Korea and back with such a smart, witty, observant insider. And have I mentioned the writing? So many times I said to myself as I read a particularly delicious sentence or description in Re Jane why can’t I do that?”

—Elinor Lipman, author of The View from Penthouse B

“Patricia Park displays her keen observation skills, her penchant for finding le mot juste (be it in English or Korean) and her natural gift for story telling in her witty debut novel, Re Jane. Not only does this charming novel entertain, especially with spot-on descriptions of people, but it also opens a window into the Korean culture. This may be Patricia Park’s first novel, but it won’t be her last.”

—Firoozeh Dumas, bestselling author of Funny in Farsi

“This is a richly imagined and engrossing novel, and also an important work that marks what it means to be American now. Park’s writing is remarkable for its tenderness and honesty.”

—Sabina Murray, author of Tales from the New World and The Caprices

“Even with its appealing echoes of Jane Eyre, Patricia Park’s first novel is a true original–a smart, fresh, story of cultural complications that hasn’t yet been told in quite this way. The funny and shrewdly observant narrator won me over on the very first page.”

—Stephen McCauley, author of The Object of My Affection

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In