READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

The Flaming Corsage begins with the “Love Nest Killings of 1908.” From this dramatic, bloody scene in a Manhattan hotel room, Kennedy moves his plotline both forward and backward, the events ranging from 1884 to 1912. Eventually, and ever so deliberately, much of the truth about the love nest killings will be revealed. Surprises are in store.

At the heart of the novel are two characters who will be somewhat familiar to Kennedy readers: the Irish American playwright Edward Daugherty and his wife, the upper-class Protestant Katrina Taylor Daugherty. Edward woos the enchanting and mysterious Katrina and she seems to reciprocate his love; however, a catastrophic fire changes everything for the young married couple, as Katrina loses part of her family and is irreparably scarred by “the flaming corsage.”

The development of Edward’s play writing career coincides with Katrina’s increasing withdrawal from the world of reality. Their lives become more and more complicated as mutual adulteries surface; Edward’s with a voluptuous actress and Katrina’s with the young Francis Phelan.

Ever present is Kennedy’s Albany; the details of the old Irish North End, where Emmett Daugherty receives his church’s last rites, and the elegant Elk Street, where the imposing and austere Taylor mansion stands. But The Flaming Corsage also portrays some more unsavory parts of town, depicted with acute precision in venues like the red-light tents of the State Fair.

ABOUT WILLIAM KENNEDY

William Kennedy was born on January 16, 1928 in the predominantly Irish neighborhood of North Albany, New York. His first recorded experiences as a writer occurred during his high school years at the Christian Brothers Academy, where Kennedy wrote for the newspaper. While earning his B. A. at Siena College, Loudonville, New York, Kennedy edited the school’s newspaper and served as associate editor of its magazine.

In 1956, Kennedy worked as a columnist and an assistant managing editor of the Puerto Rico World Journal, a San Juan newspaper for an English speaking audience. The paper folded after nine months, but by the end of the next year, Kennedy had already earned jobs as a reporter for the Miami Herald, a freelance journalist for Time-Life publications, and a reporter for Knight Newspapers. He had also married Dana Sosa, a dancer, whom he had met in Puerto Rico.

In 1959, Kennedy became managing editor of the San Juan Star. Two years later he attended Saul Bellow’s creative writing workshop at the University of Puerto Rico at Rio Piedras, and resigned his editorship to devote his full time to writing fiction.

Kennedy went home to Albany in 1963 to care for his father, who was living alone. He accepted part-time work from theAlbany Times Union. By 1965, his articles about Albany’s slums and racial integration had won state and local awards and were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Between 1968 and 1970, Kennedy was film critic for the Times Union, and in 1969 published his first novel, The Ink Truck. The reading world had been introduced to William Kennedy’s Albany and to the first of his fictional individualists, the striker Bailey.

In 1975, after painstaking research and numerous narrative experiments, Kennedy published Legs, a fictional account of the rise and fall of Jack “Legs” Diamond. In 1978, Kennedy’s Phelan family made its first appearance in published fiction, Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game, bringing the reader to the streets of Albany’s “nighttown,” a world of gamblers, kidnappers and political bosses. In 1983 Kennedy published O Albany!, a collection of essays on Albany’s neighborhoods and ethnic history.

In 1983, Kennedy won a prestigious MacArthur Foundation fellowship. In 1984, he won the Pulitzer Prize, The National Book Critics Circle Award, and a PEN-Faulkner award, all for Ironweed (which in 1987 was made into a feature film). During that same year Kennedy enjoyed “A City-Wide Celebration of Albany and William Kennedy” hosted by his city in pride for its native son.

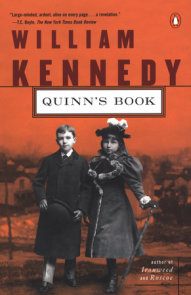

After writing the screenplay for The Cotton Club in 1984, Kennedy wrote the nineteenth-century historical novel Quinn’s Book, at whose center is a newspaper man turned fiction writer. In 1992, with Very Old Bones, Kennedy returned to the family Phelan. Riding the Yellow Trolley Car: Selected Nonfiction appeared in 1993, and in 1996 Kennedy published The Flaming Corsage, which he is currently adapting for a feature film for Universal Pictures.

It has been said time and time again that Kennedy has done for Albany what Joyce did for Dublin. More than a mere delineator of place and recorder of details, Kennedy has repeatedly succeeded in telling stories of unmistakably original characters who struggle against what, to borrow a few words from Hamlet, are life’s slings and arrows.

William Kennedy and his wife, having raised three children, continue to live near Kennedy’s inexhaustible Albany. In a book-filled and memorabilia-crammed study, the Albany Cycle continues.

PRAISE

“Kennedy’s most commanding performance since his Pulitzer Prize-winning Ironweed.” — The New York Times

A CONVERSATION WITH WILLIAM KENNEDY

Conducted by Vivian Valvano Lynch

Much historical information is contained in The Flaming Corsage, and a particularly memorable chapter that depends on solid research is “Edward Delivers a Manifesto.” How did you go about conducting your research?

The “Manifesto” was a consequence of my visiting Ireland in 1973. I wrote some pieces then; but one I never wrote was a piece on Connacht. I saw that situation over there, saw how people had to live, had to take endless rocks out of the land, to exist on small patches of soil. It was a horrifying thing, like a lunar landscape. It still exists; it’s a monument to desolation. I always wanted to use that someplace. I tracked it down historically for the “Manifesto.” I found out about Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland. It became a historical quest from one book to the next to find out how the Irish survived, where they went. I used Cromwell’s letters, British historians, Irish historians. On other matters, such as the Delavan Hotel fire, that was historically accurate. There was such a fire and it burned exactly when I said, as to day, date and time, and with similar consequences. Of course, I had to invent the details of the characters’ lives. I researched all the news coverage of those days. But, again, the burning of the hotel, which was such a famous place, and the deaths of so many Irish servant girls; these things made me want to go back and take another look at them and use them.

Edward Daugherty is a playwright, and significant portions of The Flaming Corsage recount his play, The Flaming Corsage. But, of course, it is your play. What was it like to be an experienced novelist attempting to write in a different genre? Has there been a secret ambition to be a playwright all along?

I thought as a beginning writer, writing short stories, that maybe I would be a playwright. But that didn’t last long. I wrote one play in the late 1950s, but I decided I wanted to write novels. However, I continued to be interested in theatre. After Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game, in which I invented The Flaming Corsage as a play and created Edward as a playwright, it became a matter of becoming equal to my own imagination. I conceived the novel The Flaming Corsage in 1977; I was already working on it when Billy Phelan was published. I wanted to write a three to four act play, as a coda for the novel. I kept that thinking alive for a number of years because I didn’t get to write the novel then. Other plays of Edward’s became important to me, for example The Car Barns in Ironweed and The Baron of Ten Broeck Street. The impetus was to use an artist of that age. Theater was new, the Irish were involved, for example, O’Neill. Edward would precede O’Neill.

An important narrative device in The Flaming Corsage is the non-sequential presentation of the plot. However, the book features datelines that the reader can use for chronological reference. Could this be a bit of homage to the techniques of journalism, the field in which you began your writing career?

I think the homage is to the reader, to keep him on target. It’s a very complicated story. If you didn’t have those dates and titles, you could easily get confused because of the leaps in time. It was an evolutionary form. I didn’t set out to write a back and forth kind of story. Originally, I didn’t have the “Love Nest Killings” at the beginning. When that became the opening, that set a pattern I had to follow, which was to maintain the mystery. It became a slow unfolding, through the inquest, various press reports, the pursuit of information by Edward (including his going to see Melissa), until you eventually understand the nature of the whole story’s evolution. I wanted to parallel that with the story of the marriage. At a certain stage, the two parallel stories come together; they fuse. It was the matter dictating form.

Of Katrina Taylor Daugherty, who had already appeared in some of your novels, most notably Ironweed, you said in an interview in 1989: “I love Katrina” (South Carolina Review 21.2, Spring 1989). How do you feel about her now, having written more of her story?

I’m still very intrigued by her. She’s probably the most complicated woman I’ve created. As an achievement of creating character, I think she stands alongside Helen Archer in Ironweed. They’re so different, but they are equally complex. I have great fondness for Katrina’s eccentricities. I’m writing the screenplay for the novel now, and I have to rethink her all over again.

Many characters appear and reappear in your cycle of novels. How do you go about deciding when to reintroduce (or finish) a character?

I never necessarily finish a character. I don’t know whether I’m finished with Katrina; I might be. I’m not finished with Legs. Billy Phelan could come back again, as he did in Very Old Bones. These characters emerge as my imagination focuses on a past era or a past story, maybe the unfinished story of one of them that I have to tell. I know that for Daniel Quinn, of Quinn’s Book, I have a novella or a long short story or maybe a novel. He’ll take a role; he may not be the central character. I just never know; they pop up in my imagination.

Which contemporary fiction writers do you read?

The writers don’t all have to be alive, do they?

No; why don’t you tell me what you’re reading?

I’m still reading Faulkner, and Beckett. I just read a segment of the new DeLillo novel and books by Cormac McCarthy, and Philip Roth. I just finished a wonderful novel, In the Memory of the Forest, by Charles T. Powers. It’s a book of post war Poland under the Communists, and he carries it to the present day. It’s an excellent piece of work. I’m sorry to say he died before he could see the book in print.

In today’s multimedia influenced world, how would you define the role of fiction and the fiction writer?

I suppose it will be as important as it always has been in the creation of story. The storyteller isn’t going to change, no matter how the media changes. I think that serious fiction is suffering some decline and has been for a number of years, and I hear the same sad stories from Europe. But I have great faith that fiction writing will continue to be one of the most important things writers can do with their talents. I love it. I’ll do it until I die.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS