Author Q&A

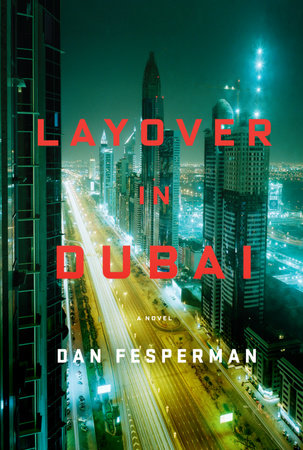

Q: What was your inspiration for Layover in Dubai, the story of Sam Keller, a corporate auditor

visiting Dubai, who unwittingly becomes involved with a lethal mix of mobsters, prostitutes and

crooked cops?

A: A few years back it seemed like every time I opened a magazine there was some new story or

photo spread about all of the bizarre things being built, dredged or conjured from out of the desert

in Dubai – those islands shaped like the map of the world, the underwater hotel, the ski slope in the

mall. Then I started reading about the underbelly to all of that prosperity, with the huge labor camps,

the endemic prostitution, the wild ex-pat lifestyles, and so on. My fascination finally reached a point

that I wanted to set a book there, so of course I had to go see it for myself.

Q: You describe Dubai as “. . . the sharp glass edge of a barren land.” What about this city

fascinates you?

A: The contrast of extremes, mostly. Desert meets Gulf. Explosive wealth meets sleepy culture of

smugglers and pearl divers. Islam meets the wild, wild West. I’m also intrigued by the whole idea

of a country that has grown so fast that all of its major institutions, from the police to the courts to

the governing bureaucracy, are pretty much staffed by foreigners. It’s a little bit like a fabulously

wealthy family with lots of children. At some point the parents blithely sort of throw up their hands

and say, well, I guess we’ll just have to go out and hire a bunch of nannies, tutors, gardeners, cooks,

shoppers and servants to take care of everything. It is a paternalism that, materially, treats its people

very well, but does so with a growing level of detachment. And eventually you reach a point where

you wonder if the inmates are running the asylum.

Q: You’ve said, “Dubai is not an easy place to get to know in a hurry.” What sort of research did

you conduct in order to write this book?

A: Months before I ever went, I started with a few contacts in Dubai, who introduced me by phone

and by email to more, who in turn introduced me to others. By the time I flew over I had arranged

interviews with people in various walks of life – some of them Emiratis, some of them ex-pats – who

then connected me with others while I was there. I also visited as many of the locations as possible

– brothel bars, labor camps, construction sites, the port, the souks, some of the older neighborhoods,

and, of course, the malls!

Q: You depict a fascinating dichotomy in Layover in Dubai: Hard partying vacationers living side

by side with a strict local culture of modesty and piety where women dare not show their faces

in public. For those who have never visited Dubai, can the casual visitor feel this divide or have,

in Layover in Dubai, you let us peek behind the curtain?

A: At one level you feel it everywhere you go, because the locals – especially the women – stand out

so obviously simply by the way they’re dressed. So you do have this vague sense that this other, very

different life is going on just beneath the surface. But the glitz of all the spectacle and newness is often

so blinding that you barely get any sense of the way the place used to be, not so long ago. Without

working at it, you don’t get much sense of cultural continuity from that earlier era. So I had to talk to

a lot of people and do a lot of reading – oral histories, past narratives, and so on – to get a feel for that,

and I’ve tried to imbue it in the Emirati characters in the book, especially Anwar Sharaf, who, despite

being an open-minded fellow, is a bit overwhelmed by the pace of change.

Q: Sam Keller finds himself in the Sonapur Labor Camp, working to build a new high-rise in

Dubai. You’ve said that while doing your research in Dubai you visited a labor camp and that you

were “chased out . . . by image-conscious security personnel.” What do they have to hide?

A: To put it bluntly, they’re like something out of a nightmare passage from Dickens – all-male slums

and ghettoes, populated mostly by impoverished workers from the Indian subcontinent. The camps

were built specifically to keep the workers under control and under wraps, partly so that none of the

vacationers and party-hearty folks ever has to be troubled by seeing them except at the work site. It

is a life of indentured servitude, and their jobs are harrowingly dangerous. After the financial crash –

which the book predates – a few camps became virtual ghost towns when some of the smaller

construction companies went under, so for a while you had thousands of marooned men living in

buildings with no electricity or running water. They had no salaries and no way of getting home.

Q: What do you think Dubai will look like in 20 years? 50 years? 100 years?

A: Even a 20-year jump might be too hard to envision, given the rate at which the place has changed

in only the past ten. Although the one good effect of the crash is that it has at least forced Dubai’s

builders and planners to take a deep breath as they wonder if they’ll ever be as solvent as before. They

also have to wait and see if all those places they built will ever be filled. Dubai seems a bit sugarshocked

right now, like a child that just spent an hour gorging on candy and then threw a tantrum

and collapsed on the floor. But for a while there it had the feel of the kind of dizzy, forward-lunging

society that Alvin Toffler must have had in mind when he wrote Future Shock back in 1970.

Q: What’s next for you?

A: I’m working on a novel in which the main character lives out on the cutting edge of modern

warfare. He’s an Air Force captain who commutes to the Nevada desert to pilot a Predator drone in

the skies of Afghanistan, from 7,000 miles away. He blows up bad guys, pokes around the carnage of

the aftermath, and then drives home to pick up his kids from school in the ‘burbs of Vegas – speaking

of disorienting lifestyles. Another case in which I was attracted by a contrast of extremes, I suppose.

FOR BOOKING INFORMATION, contact:

Sara Eagle, Publicist

212-572-2195 / seagle@randomhouse.com