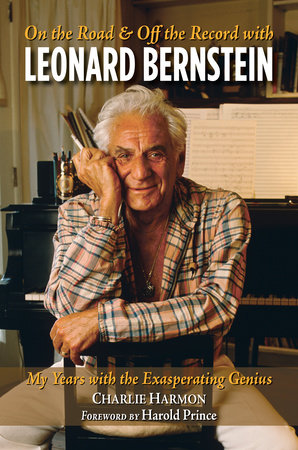

On the Road and Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein

By Charlie Harmon

Foreword by Harold “Hal” Prince

By Charlie Harmon

Foreword by Harold “Hal” Prince

By Charlie Harmon

Foreword by Harold “Hal” Prince

By Charlie Harmon

Foreword by Harold “Hal” Prince

Category: Arts & Entertainment Biographies & Memoirs | Music

Category: Arts & Entertainment Biographies & Memoirs | Music

-

$16.99

Feb 11, 2020 | ISBN 9781623545420

-

Jun 18, 2019 | ISBN 9781632892379

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Inheriting Magic

Giant Love

Two-Headed Doctor

Never Give Up

Carl Perkins

Joan Didion: Memoirs & Later Writings (LOA #386)

Over to You

Jane Austen: Visual Encyclopedia

The Name of This Band Is R.E.M.

Praise

A gossip-filled memoir of life with a musical superstar.In his debut book, music editor and arranger Harmon recounts in vivid detail four exhausting, exhilarating years as assistant to the mercurial maestro Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990). At the age of 30, the author was a clerk at a music library when he answered an advertisement to work for a “world-class” musician. The applicant, the ad noted, “must read music, be free to travel,” and “possess finely-honed organizational abilities.” In the course of a three-hour interview, Harmon learned that the musician was Bernstein (called LB throughout the book), who was embarking on a strenuous schedule of performances around the world. The author was not sure he had the stamina for the job, which involved handling phone calls, mail, and appointments; packing and unpacking scores of suitcases for every trip; taking notes during rehearsals and performances; and—a task that proved especially challenging—making sure LB, infamous for his “celebrated libido” and drunken rants, did not generate negative publicity. Despite some reservations about his capabilities, in January 1982, Harmon set off with Bernstein and his entourage to Indiana University for a six-week residency, during which the composer began work on an opera. LB was a handful: demanding, impatient, and given to “bouts of fury and bratty behavior,” which Harmon attributed to his enduring grief over his wife’s death, in 1978. That behavior was exacerbated by heavy drinking and use of Dexedrine, fueling “drug-induced mania” followed by overwhelming depression. Drawing on his daybook, Harmon gives intimate accounts of LB’s performances, teaching, creative process, and uncompromising standards—in the midst of a “three-ring circus” peopled by a large and sometimes-divisive cast of characters. Most troubling to Harmon was LB’s imperious, “blatantly self-serving” manager, who wore Harmon down with cruel bullying. Exhaustion and depression eventually led Harmon to seek psychiatric help, though he admits that his intimacy with LB’s musicianship gave him “a remarkable education.” An affectionate portrait of an eminent musician who was driven by demons.

—Kirkus Reviews

Harmon knew that most of Leonard Bernstein’s personal assistants didn’t last very long on the job. He quickly learned, too, that working for “Lenny” meant that he would have to give up any semblance of a personal life. Putting his life on hold, though, and “working alongside a creative genius” game him, he writes, “the strongest sense of purpose I’d ever had.” For four “scorching” years, Harmon’s responsibilities included answers the phones, handling Bernstein’s mail and appointments, and carrying his luggage while also acting as a gatekeeper, valet, and librarian. Harmon’s account of life working for an “exasperating” genius is breezy and anecdotal even when he is discussing his own mental-health issues and self-doubt. He meets countless movers and shakers in the arts and politics as he travels with Bernstein and his entourage around the globe and works alongside Bernstein at the famous Dakota building on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Harmon’s personable and warm account of what it was like to work for one of the twentieth century’s musical giants casts new light on Bernstein and his world.

—Booklist

Harmon, a classically trained composer and arranger, approaches his subject from an interesting point of view. For four years in the 1980s, Harmon was the maestro’s personal assistant, accompanying him through a punishing schedule of composing, performing, and recording. This multifaceted perspective gives readers plenty of salacious gossip paired with insight into Leonard Bernstein’s remarkable artistic achievements later in life. The volume adroitly balances reporting on Bernstein’s personal hygiene, profligate love live, and bouts with depression with an informed discussion of his professional output during the period. Throughout, Harmon weaves his personal experience4s as a gay man in a precarious profession. The net result is a volume that gives equal weight to Bernstein’s struggles as a composer to make a deadline on a commissioned opera and his expirees in applying Right Guard to his forehead to manage the sweat collecting on his brow while he conducted. VERDICT: More memoir than biography, this engaging account will do well in general collections.

—Library Journal

In this tell-all book, Charlie Harmon—orchestra librarian, music arranger, and editor—recounts his four exciting, draining years as assistant to Leonard Bernstein. He describes his job as manager of Bernstein’s day-to-day life as a whirligig of phone calls, appointments, music scores, and traveling. But managing Bernstein involved a lot more. The maestro was demanding and prone to “bouts of fury and bratty behavior.” Harmon was given the job of monitoring Lenny’s “celebrated libido” for young men and keeping this information from the press.

Bernstein’s manic behavior was exacerbated by the vast amounts of Dexedrine he consumed and, of course, the alcohol. These frenzied episodes were often followed by major bouts of depressing, when Bernstein wouldn’t shave, shower, or sleep for days. Contributing to his frenetic behavior was grief over his wife Felicia’s death in 1978. According to Harmon, Lenny seemed haunted by her. He seemed at times to be pursued by demons—driven to exhaustion by a relentless schedule of conducting, teaching, and composing. He sometimes complained that no one cared about him as a person.

We get a good sense of life with Lenny from 1982 to ’86 through the lens of Charlie Harmon. We travel all over the world with the maestro, and we meet plenty of celebrities along the way. For Harmon, his time with Bernstein was a mixed blessing. He ended up suffering from severe exhaustion and depression. On the other hand, it provided him with an extraordinary education. His four years as assistant to a genius were a self-revelatory journal as well as a musical one.

—The Gay & Lesbian Review

When I received Charlie Harmon’s memoir about Bernstein, my first thought was “ANOTHER Bernstein book? I just reviewed Dinner with Lenny!” After a short time, the running theme dawned on me: Two thousand eighteen is the Bernstein centennial, so it’s only natural that there would be an effusion of Bernstein-related literature.

Charlie Harmon was LB’s (Harmon’s moniker for him) assistant in the last decade of the Maestro’s life. As a recent college graduate and a composer with the all-too-relatable predicament of needing to find steady employment, Harmon submitted an application for a laughably unassuming ad in the classified section of his newspaper: an assistant for a “world-class” musician. To his amazement, he got the job after some interviews with LB’s manager Harry Kraut, who briefed him on Bernstein’s many needs, quirks, and manically busy schedule. If that wasn’t enough to keep him busy, Harmon’s biggest task, said Kraut, would be to keep LB on track to fulfill the commission for his (seriously underrated) opera A Quiet Place.

With this gripping memoir—is it even possible to write a boring book about Bernstein?—Charlie Harmon adds a crucial piece to the Bernstein puzzle: an up-close-and-personal look at a turbulent, complex man who happened to indubitably be one of the greatest musicians of his time. Harmon experienced firsthand that LB was not always the fatherly teacher with his belovedly electric podium presence. He could be irascible, childish, egotistical, and blunt. The story about their first meeting sums it up to a T: It was Indiana in 1982, and Bernstein returned to his lodgings with an entourage of students. He was bundled up in a white parka, and he hadn’t shaved, showered, or slept in days—oh, and he was clearly three sheets to the wind. Still, LB gulped down the gin he took out of Harmon’s hand, and when Harmon protested, he snarled at his stunned new assistant, “You don’t talk that way to the rebbe!”

Even after this rocky start, and through relentless travel, insomnia, all-nighters, and one-night stands, the relationship between the two developed into one of mutual respect. Besides, there was a more than valid explanation for LB’s sometimes erratic behavior: The Maestro, according to Harmon, was in depression, grieving the death of his wife, Felicia, and was self-medicating with scotch, amphetamines, music, sex, parties, word games, and his famous four-pack-a-day smoking habit.

Anybody interested in Bernstein, as I am, should read Charlie Harmon’s book, due for release in May 2018. As well as being a unique portrait of the later Bernstein, it’s a loving tribute to the unglorified behind-the-scenes staff of devoted assistants, all with their own personality traits that made for quite a bit of drama. (LB’s secretary, Helen Coates, could be overprotective in a motherly way, and Harry Kraut just plain ruthless and manipulative, often driving Charlie Harmon and others to the breaking point.) If Bernstein appeared to work hard—which he most certainly did—it is because it was made possible by people like Harmon, who acted as a sort of emotional confidant to Bernstein in addition to handling everything from copying music to handling luggage to managing appointments. If nothing else, On the Road is a colorfully written, unforgettably entertaining and unputdownable book, and is available just in time for LB’s 100th birthday. Unreservedly recommended.

—Fanfare Magazine

In this tell-all book, Charlie Harmon—orchestra librarian, music arranger, and editor—recounts his four exciting, draining years as assistant to Leonard Bernstein. He describes his job as manager of Bernstein’s day-to-day life as a whirligig of phone calls, appointments, music scores, and traveling. But managing Bernstein involved a lot more. The maestro was demanding and prone to “bouts of fury and bratty behavior.” Harmon was given the job of monitoring Lenny’s “celebrated libido” for young men and keeping this information from the press.

Bernstein’s manic behavior was exacerbated by the vast amounts of Dexedrine he consumed and, of course, the alcohol. These frenzied episodes were often followed by major bouts of depressing, when Bernstein wouldn’t shave, shower, or sleep for days. Contributing to his frenetic behavior was grief over his wife Felicia’s death in 1978. According to Harmon, Lenny seemed haunted by her. He seemed at times to be pursued by demons—driven to exhaustion by a relentless schedule of conducting, teaching, and composing. He sometimes complained that no one cared about him as a person.

We get a good sense of life with Lenny from 1982 to ’86 through the lens of Charlie Harmon. We travel all over the world with the maestro, and we meet plenty of celebrities along the way. For Harmon, his time with Bernstein was a mixed blessing. He ended up suffering from severe exhaustion and depression. On the other hand, it provided him with an extraordinary education. His four years as assistant to a genius were a self-revelatory journal as well as a musical one.

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In