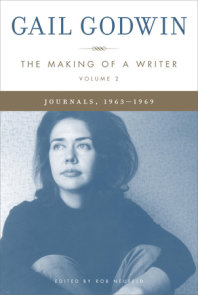

Author Q&A

A Conversation with Gail Godwin

Rob Neufeld is the book reviewer for the Asheville Citizen-Times and

director of the program “Together We Read” in North Carolina. At

present, he is editing volume one of Gail Godwin’s diaries.

Rob Neufeld: One of the most distinctive features of your writing is

that you keep adding layer after layer of history and attitude to your

characters and yet somehow manage to maintain the drama. Is this

layering a method of yours?

Gail Godwin: The characters and the places have to be as real as possible.

I have to know what the characters are seeing and thinking. I

end up developing much more than I use, and sometimes I include

passages that I later have to take out. When I started The Finishing

School, I had gotten stuck in the opening on the story of how Justin’s

grandmother had met her husband. My mother said to me, “I think

you need to get back to the drama.”

RN: The Finishing School is just a little over three hundred pages.

That’s a nice length for a novel, don’t you think?

GG: I wish I could make the novel I’m working on now that length

because I love that length. Father Melancholy’s Daughter was over

four hundred pages, but it didn’t feel like it. With my Christina stories

[autobiographically based stories that have contributed toward

Evenings at Five and other pieces], I’m building one large work that

I’m calling The Passion of Christina.

RN: The Finishing School, along with Father Melancholy’s Daughter,

are two of the most cohesive yet complex novels I’ve ever read.

There are many great novels that aren’t so much of one piece. They

have hinges that show. How do you make a long novel that has the

continuity of a short tale?

GG: I have been pulling out big chunks of the novel that I’m working on

presently—Queen of the Underworld—in order to reposition them or

break them up into absorbable pieces. My goal in this novel is to sustain

three months of the heroine’s experience, seeing how her mind works—

with no foreshadowing allowed. I want the reader to be there with her. I

don’t want any sidetracks to slow down the journey, which is very much

of-the-moment. Sometimes, I am amazed at how much I discard from my

drafts—months of work, including long forays into flashbacks. I ask myself,

What is the trajectory I want? Can I put the information across without

what Kurt Vonnegut used to call my “sandbagging flashbacks”?

RN: Could you talk a little more about the process by which you

maintain continuity?

GG: I make diagrams of my novels with a ruler. I turn a page sideways

and write the name of my novel on top. Then, I take a ruler and draw

vertical lines to make ten divisions and a horizontal line to make twenty

for the number of chapters. I start planning what happens where. If I

have a character offstage for too long, I know I have to bring him or her

back. I’ve done this with every novel I’ve written since The Perfectionists.

It takes me two, three, or fours years to complete a novel. Over that

period, you tend to lose track of things, so you have to keep refreshing

yourself. I also write myself blue papers (after the kind of paper I’d

once used in my typewriter). They’re sermons or pep talks to myself:

“Well, Gail, you think you’re stuck. Why? You have a party with thirty

Cuban exiles at it. What are they doing? You just have to get to the

party and start anywhere—with the food, anything.” Writing The Finishing

School, I knew how many chapters it would become because I

made notes of which scenes would go where. Since Justin hangs on to

Ursula’s every word, I knew I could have Ursula dole out her life story

in bits anytime anything suggested something.

RN: Are discarded parts the seeds for other novels and stories?

GG: The one I just threw out was based on something that happened

to me at St. Genevieve’s [school]. It was about trying to talk with

Cubans. I was sorry to lose it. It was twenty pages long. Then I

thought, This would make another good Christina story.

RN: In the beginning of The Finishing School, Justin reveals that

Ursula DeVane has “claimed a permanent place in the theater of my

unconscious.” Theater is an important concept for you. Madelyn Farley,

a key character in Father Melancholy’s Daughter, is a theater designer.

Justin Stokes becomes a stage actress. In what ways does the

theater of the unconscious resemble theater?

GG: There is a finite stage in the theater of the unconscious. There is

a finite number of actors—not fifty, but only five or ten. The story

crystallizes into figures of necessity. The drama must be riveting, and

the setting has to be a place where you’d want to live for a few hours.

Then, there are certain sets that you return to again and again in your

imaginative theater, like recurrent dreams. I have Asheville sets. One is

St. Mary’s [Episcopal Church]. One is St. Genevieve’s. They don’t

represent themselves. They represent points of growth. They stand for

attitudes and challenges. You can learn so much from dreams.

[After a couple of moments of silence over the phone]

GG: My cat is vocalizing.

RN: Is that the cat [who becomes a protective spirit in Evenings at

Five]?

GG: That’s the cat. I named him Bud in Evenings at Five after my

friend, a Jungian analyst. The cat’s real name is Ambrose.

RN: There’s so much fun in the world, isn’t there?

GG: I know it!

RN: Later, I’ll want to talk about your sense of humor. Now, let’s talk

about your sense of realism—particularly, how you represent what goes on

in people’s minds. Aren’t people’s thoughts at any moment a big mishmash?

GG: Not so much a mishmash. The actual process of thinking has a

tempo of its own. It moves very quickly. Try tracing back your present

thought to the thoughts that had initially led you to it. At first, you

think you’ve gone through some astonishing non sequiturs, but I believe

you’ll usually find that they are all ordered in some way. One thing leads

to another and you discover patterns. Everyone has his or her very own

cloaking pattern. This kind of pattern—which is like storytelling—

may involve a tempo, a costume, purposeful omissions, and intuitive

progressions. The subconscious is your ally in coming up with fictions.

RN: Ursula DeVane says that her mother haunts her. Is a person’s

mind a scary thing?

GG: A person’s mind is full of ghosts, and the main ghosts have real resonance

and real power. They have vibrato. Think of how much you’d know

about a person if you knew the main ghosts that haunted him or her.

RN: What kind of an adventure is it to create a character and go into

his or her mind? Do you see that as an adventure?

GG: That more than anything else is what keeps me wanting to

write—to get to understand the mind of anyone. José Ortega y Gasset

calls it transmigration into other souls—seeing a situation from

the other’s point of view, or trying to. Barbarians don’t do it very

much. It’s hopping into someone else’s being and living another life.

RN: On your Web site, under “tips for writers,” you suggest that a person

write a story first in the style of Ernest Hemingway and then Anton

Chekhov. What would it mean to write a story in the style of Gail Godwin?

You seem particularly interested in the idea of transmigration.

Justin “becomes” Ursula and “becomes” her fourteen-year-old self.

Empathy is important to other characters as well. Justin’s grandfather

“becomes” the slaves.

GG: And the snake!

RN: That’s a good trick! At any rate, do you acknowledge that kind

of empathy as one of the distinctive features of your work?

GG: Yes. In the novel on which I am now working, Queen of the Underworld,

the heroine is a young newspaper reporter in Miami, and

she’s staying in a hotel with Cuban exiles. One of the exiles had been

an owner of a sugar plantation, but now he’s at the front desk. He

doesn’t speak much English. It’s interesting to notice how being an exile

changes the way one moves. Your whole posture changes when you

don’t speak the language. The reporter then imagines herself in another

country as an exile. It’s an exercise in empathy for her.

RN: How do you go about becoming someone else?

GG: I usually start with visualization. I see other people—what they’re

wearing, what their gestures are—going onto a train, going into a

restaurant. They’re coming in thinking what, I wonder. With Aunt

Mona, my first thought was, What kind of person would be the opposite

of the kind whom Justin has been raised to admire—someone who

is not reserved, who talks all the time about starting with nothing?

Then I ask, What would she be like? How would she move, how would

she furnish her house? It occurred to me that that character would be

Justin’s aunt, and Justin would have to go live with her—with a person

who would not have been admired in certain circles in Virginia. Then, I

had to visualize Aunt Mona—her birdlike qualities, her earrings. At a

house I’d visited once, I had seen plastic paths laid down so you

wouldn’t have to walk on the rug. I thought it was bizarre and touching

at the same time because it said, “I’m not used to having things that are

expensive.” Eventually, I start hitting the levels where I become the person.

For example, I see Mona’s sterling qualities. She’s a fighter and

wants to better herself. She’s quite generous and warmhearted.

RN: That’s a good acting method. Are you an actress?

many years] told me I was.

RN: At one point Justin says about Becky, “One day . . . I am going to

crack the code of Becky.” Is Becky’s story waiting to be told?

GG: Becky’s, no. But there is a certain kind of character who has fascinated

me throughout my life—a quiet, inscrutable person who appears

to have who-knows-what going on inside. I met a model of this Becky

when she was three—and now she’s thirty-two. I can see how she’s doing.

RN: At the end of The Finishing School, you suggest that having

multiple personalities—or at least acknowledging them—is the secret

to sanity. Going through transformations and acknowledging multiple

personalities makes Justin whole.

GG: Yes, I agree. Justin does keep transforming. Being able to acknowledge

having many personalities goes against the picture people

have of themselves. The trouble with the phrase “multiple personalities”

is that people think of cheap movies. You know, the doctor helps

someone get rid of all the personalities except one, and that one survives,

and then the person is healthy. We need another phrase. I like to

say internal cast of characters.

RN: Can Justin accept the fact that one of her personalities—or internal

characters—is a monster and still be okay?

GG: If Justin can recognize that then she’ll be able to put it in its

place. We all have monsters. Justin’s monster is the ability to close

down when she feels herself threatened or being turned into something

against her will.

RN: Let’s talk about how you set the stage for your stories. In The

Finishing School, you have a kind of score. Chopin’s Scherzo in B-flat

minor and Franz Schubert’s “Der Doppelgänger” play important

parts. How did these pieces come to you?

GG: The most important piece is the one that Julian plays as an allclear

signal. I heard Robert play that, and it’s diabolic. It summons

trouble. Also, it’s very hard to play. Above the sound of gathering

force, there’s a cascade of relief. I chose it intuitively.

RN: Would you be opposed to the book’s being published with a

soundtrack?

GG: It should be. My late editor, Alan Williams, when he called me

to talk about The Finishing School, played the Scherzo and then came

on to talk. Music can express many things that words cannot. Do you

know the story “The Jolly Corner” by Henry James? A man comes

back to New York and haunts his family’s town house in order to confront

the ghost of who he would have been if he had stayed. James’s

description of the climactic moment—the meeting of the two—

doesn’t work. The ghost comes downstairs and he’s missing two fingers,

which is supposed to represent that he had become a powerful

business mogul. Music could have made it work better. For an eerie effect,

you could tune violins up one whole tone, for instance.

RN: How have you collaborated with Robert on musical compositions?

GG: We created twelve works together, including operas. Magdalen

at the Tomb and Anna Margarita’s Will can be heard through links on

my Web site, www.gailgodwin.com.

RN: Transformation is an important theme in your work, and it’s an

agonizing process for characters. Why is it so hard for people to realize

who they’re supposed to be?

GG: That’s what my new book is about, transformation. The other

key word—the heroine’s key word in the book—is usurpation. She

has gone through her life resisting usurpation. Other people and

forces in her life have been trying to usurp her for their own reasons.

RN: Is that what Ursula was doing with Justin?

GG: Yes. Justin was the perfect blank page. Ursula was the most

powerful person in her life when she was fourteen. Justin was almost

completely drowned in Ursula’s personality until she knowingly

drowned, in a sense, in that pond. Even then, you could say that Justin

has been controlled by Ursula because she was repeating Ursula’s betrayal

of her mother.

RN: You mark characters’ passages with epiphanies. Do you like that

term, “epiphany”?

GG: The term was drummed into me at graduate school. It belongs

to James Joyce. “Shock of recognition” is good, but we need to come

up with our own term. The quickening moment—I like that. It has to

do with the speeding up of the story, as well as bringing things to life.

The quickening moment for Justin—when everything comes together

and comes to a head—is when she dives into that pond. She is, among

other things, asserting her ability to swim. She is also trying to protect

Ursula from being discovered with her lover.

RN: Just before Justin goes off and instigates the story’s big event,

she witnesses the demolition of her subdivision’s old farmhouse. This

leads to her getting angry at her mother for her indifference about

this, and that leads to her running off to see the DeVanes. The fall of

the farmhouse makes the plot work, but is it also symbolic?

GG: The farmhouse represents the place where Justin could be herself,

where she could escape the conformity of her new home. It reminded

her of her old home. She had a great need for it. When children who

were playing around the farmhouse saw Justin coming, they left the

place to her. They recognized a need in her that was so strong, it scared

them. It spooked them. The farmhouse is a kind of symbol, but with a

good symbol, you never can get to the bottom of it.

RN: There is a lot of humor in your books. Aunt Mona is a hilarious

character.

GG: I had one person come up to me once and ask me why I was humorless.

I’m not. I’m glad you mention the humor. There are levels of

humor, and mine tend to lie in the subtler ranges rather than slapstick.

Aunt Mona’s funniness comes from her holding on to certain beliefs

and habits with great tenacity, so there’s a strength to her weakness. You

see her asserting herself over and over again in predictable ways. You

look forward to her comment, for instance, that things would have

turned out differently for her if she had had others’ advantages. And the

contrast between her own terrible decorating style and her image of

herself as someone who can give decorating advice is comical.

RN: That’s right. When Mona warms up to Ursula because of Ursula’s

cultural knowledge, she suggests that she and Ursula might become

good friends, and that she might give Ursula some decorating tips. It’s

very funny.

GG: In the end, though, Aunt Mona is redeemed from being primarily

comic. There’s a seriousness in that.

RN: People look at your fiction and see that, for instance, the mother

characters in the stories are all very different. Yet, they keep wondering

about the autobiographical content. How did The Finishing

School come to light for you?

GG: It came out of Robert’s and my experience of living in a 250-yearold

Dutch farmhouse when we first lived together in 1973. We were not

only thrilled by it, but spooked by it. That whole landscape was waiting

to be put into a book. For a long time, I had had the idea of an older sister

living with her brother in an old house, and a young woman would

get involved. At first, my idea for the story had been melodramatic. The

girl would be pregnant and the brother and sister would take her in because

they wanted a child. They would have researched bee stings in order

to figure out how to get rid of the girl. The other thing that inspired

me was hearing Robert play the piano. You could hear him playing in

the house when you were on the terrace. I once discussed with Robert

the possibility of composing a piece for eleven cellos so that we could

hear weird music coming out of the house.

RN: How did you come up with some of the characters’ names? Jem

is the name of the boy in To Kill a Mockingbird, and “Cristiana” suggests

Christ, which contrasts with Abel Cristiana’s personality.

GG: Jem’s short for Jeremy. It’s a good Southern name. I have a feeling

that the name Jem had floated into my subconscious from To Kill

a Mockingbird. Perhaps I was trying to give a little homage. Cristiana

is a real big name around here—a Huguenot name—and I love it.

RN: Does the cover of the 1999 paperback edition of The Finishing

School accurately portray the hut and pond scenario? How does it

compare to this one?

GG: This new cover is even better. For the previous edition, I had sent

a photo of Mohonk for the artist to use. There was no hut in the

photo—that was added. This new cover is simply gorgeous, truly

strange. You see a window of a hut and you look through it. You then

see a vast expanse of field, and you realize that you’re not looking out

from the inside of the hut, but you’re looking in from the outside as if

into a vision of a vaster life. It relates to putting yourself in another person’s

place.