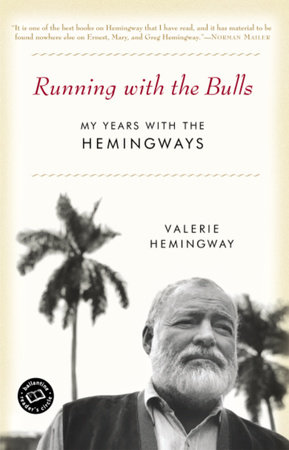

Author Q&A

A CONVERSATION WITH VALERIE HEMINGWAY

Jennifer Morgan Gray is a writer and editor who lives outside of Washington, D.C.

Jennifer Morgan Gray: Your memoir teems with vibrant, colorful detail. Did you keep a journal throughout your life and refer to it while you were writing Running with the Bulls? How long did the book take you to write?

Valerie Hemingway: I have never kept a journal as such, but I have always written down descriptions or incidents that I find interesting and want to remember. I also came from a generation of avid letter writers. I often kept copies of my own letters–using Hemingway’s method of placing a piece of carbon paper between the pages–and always the letters of others. I referred to these materials when writing my memoir. I spent about a year writing the first draft. With that draft, I composed an outline and shaped two chapters for my agent to show to publishers. When I sold the book to Ballantine in May 2003, I had a deadline of December l, 2003, to hand in the final manuscript. I kept that deadline.

JMG: Why did you begin the book with Ernest Hemingway’s funeral, then frame part of the book as a flashback to what came before. In what way was his death and burial a pivotal moment in your life?

VH: Initially I wrote my book starting at the beginning. My agent said he was anxious to get to the part where I first met Ernest Hemingway. I felt that my childhood in Ireland was an integral part of the story, and I did not want to underplay it. The agent’s comment gave me the idea that the impatient reader could be placated with a glimpse into the adventures that lay ahead. Certainly the two funerals, first Ernest’s, then Mary’s twenty-four years later, were pivotal moments in my life. A parenthesis in a way: the beginning and the end of something.

JMG: Along the same lines, do you ever consider what might have happened had you not interviewed Ernest Hemingway on that fateful assignment in Spain? What path do you think your life might have taken had you not crossed paths with the Hemingways?

VH: If I had not interviewed Hemingway, I would probably have returned to Ireland at the end of the year, found myself a job as a journalist, and lived happily ever after. (Possibly unhappily ever after, but since I’m inventing here, it might as well be happily.)

JMG: The book boasts an extensive bibliography. Are there any books that you relied on in particular, either as a frame of reference or as creative inspiration? Did you read or reread Hemingway’s novels–those published while he was alive or posthumously–while you were writing?

VH: I listed many titles in the bibliography because I am familiar with the biographies and their authors. They could be helpful to people reading about Hemingway for the first time. Also, I listed any books I had mentioned in the text. I have never read any of the Hemingway biographies through because I knew him well for two years and worked on his papers for another four years–meaning that, in all likelihood, I know more about Hemingway and his work than any of the biographers. I read extensively and always like to probe new subjects, not revisit old ones. Every few years I reread Hemingway’s works. I do this for certain other favorite authors, for instance, James Joyce and Evelyn Waugh. I most recently reread A Moveable Feast, The Sun Also Rises, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Byline Ernest Hemingway, and The Garden of Eden. I frequently read one or another of Hemingway’s short stories.

JMG: I find it amazing that after your initial meeting with Ernest Hemingway, you forgot your promise to go to Pamplona with him! To what do you attribute your casual attitude toward a writer around whom most people were awestruck? Why do you think both of you got on so well? Were you surprised when he first hired you to be his summer secretary?

VH: First of all, in 1959 I was living from hand to mouth as a freelance journalist and giving a few lessons in English: I was not at all sure that I could afford a weeklong trip to Pamplona. I had no idea that Hemingway intended to pay my expenses–except for the train fare. Hemingway was almost completely unknown to me. He was not famous in Ireland, and I had no idea he was such a revered literary figure.In Pamplona I began to observe how famous he was, not just among the Americans but also with Spaniards and foreigners. I think it was precisely because I was unaware of his exalted position that we got on so well. He could tell that I was not interested in him because he was famous. He also liked the fact that I was Irish. I was flabbergasted when he asked me to be his secretary. I thought it was his idea of a joke. He liked to play practical jokes on people.

JMG: Your time with the Hemingways enabled you to travel the world. Was there one place with which you particularly fell in love?

VH: I had been to France and Spain as a sixteen-year-old. Cuba was new territory for me, and it was there that I became close to both Mary and Ernest. It was my first trip to the tropics, and I thought it was a magical place. Cuba was an island and small–just as my native Ireland was. It was warm and welcoming and filled with music and friendly faces.

JMG: You formed a friendship with Mary that lasted through the years. When you initially met her, what was your impression of her? How did your time in Cuba after Ernest Hemingway’s death solidify your relationship? After you married Greg, how did your friendship with Mary change–for the better or for the worse?

JMG: I liked Mary from the very beginning. She was petite, pretty, with fair hair and blue eyes. She spoke her mind in a way I was not used to in a woman. She was funny, original in her ideas, could curse like a trouper, and had no haughtiness or pretense about her. When the two of us spent five weeks in Cuba after Ernest’s death, we were drawn together by the memories of our last months there with him. Mary tried to understand why he killed himself, and I was one of the few people she felt she could conÞde in and completely trust. Marrying Greg changed my relationship with Mary. She was always a little wary and distrustful of me after that. Greg really disliked her and made no effort to hide it–except when he thought he might be able to borrow some money from her to fund one of his harebrained schemes, such as buying the Irish mansion. As the years passed, I saw Mary more and more on my own, and we reestablished a close connection.

JMG: "As sure as anything, in due course Hemingway’s affection for you will wane," a friend tells you (page 83). Did you feel that this prediction ultimately came to pass? To what do you attribute Hemingway’s strong affection for you during this point in his life? What was Mary’s attitude toward you during that time?

VH: Hemingway’s affection for me did not wane, probably because he died before it had run its course. Hemingway told me that he had fallen in love roughly every decade of his life, and each time he had written a novel. Ten years before he met me he had fallen in love with the nineteen-year-old Italian girl, Adriana Ivancich. He wrote Across the River and into the Trees and then The Old Man and the Sea as a result of his passion. I think when I walked into the Suecia Hotel in Madrid to interview him, or sometime shortly thereafter, he imagined that a new and wonderful novel was in the making. At first Mary dismissed me as another hanger-on. When I arrived in Cuba she was quite distant, but she gradually included me in her activities. I’m sure she recalled Adriana’s visit to the Þnca. Mary was smart enough to realize I did not pose a threat to her marriage, so she decided to make the most of the female companionship.

JMG: You depict Hemingway’s faltering eyesight as an absolutely devastating loss to him. How did it irrevocably change his persona? How did it strike at the heart of what he could always rely upon–his writing?

VH: Hemingway read approximately three books a week, as well as many magazines and newspapers. He fished and hunted, both of which required keen eyesight. The fear of losing that capacity was devastating to him. Concern about his condition interfered with his ability to write and contributed to the deep depression that led to his decline and suicide.

JMG: You say that Hemingway had "strange standards regarding young women" (page 131). Were you ever the recipient of this attitude?

VH: Hemingway was married four times, and I suspect had many affairs with women. I can speak only of the short time I knew him, which was in the final two years of his life. He idealized young women and expected them to be pure. His attitude was paternal rather than that of a suitor. For me he was a chaperone or father figure, not a lover.

JMG: What was your initial impression of Fidel Castro, whom you met during the early years of his power? Why do you think he helped you and Mary Hemingway? Do you think the Cuba that you knew when you first visited is gone forever?

VH: I was rather enchanted by Castro, a very earnest young man with a mission. He was an idealist, a thinker, a reader, devoted to making a better country for his people. He had charm and yet was shy. He clearly admired and respected Hemingway and was greatly honored to meet the American writer. Remember, I lived in Cuba before I spent any time in the United States. I think Castro helped Mary and me out of respect for Ernest’s memory and because he had the power to do so. The Cuba I enjoyed in 1960 does not exist anymore. Indeed, few places remain the same two generations later. The Ireland I grew up in is no longer recognizable. We can preserve such places only in literature and art.

JMG: You discuss the power and the burden of bearing the Hemingway surname. How did you teach your children to handle this? How have they reacted to this book?

VH: My children first learned of their Hemingway connection when they attended school. What is important in life is who you are, not to whom you are related. I taught my children independence of mind and spirit. I gave them an excellent education. The rest was up to them. I would venture to say my strategy worked. My children have told me they are very proud of me. One son set up a website for the book as a Christmas gift, another accompanied me on my east-coast tour. My daughter and her husband arranged a reading and signing in their hometown and gave a superb party afterward to introduce me to their friends. When she Þrst read the book, my daughter wrote to me, "This is the first time I have felt proud to be a Hemingway."

JMG: The last thing Hemingway said to you was: "No matter what, no matter where we are or whatever happens, I will always be with you. You can count on that" (page 148). How have you carried those words with you in your life? How have they guided you?

VH: For many years I avoided the subject of Hemingway as much as I could. I didn’t grant interviews. I didn’t write about my encounter with Hemingway or about working with him and later his papers. Always, in the back of my mind, I have felt that I should never do anything to betray Hem-ingway’s trust in me. If someone is with you, it requires you to adhere to that person’s standards, and for the most part that is what I have tried to do.

JMG: What about Greg first attracted you to him? How did your whirlwind courtship compare to the realities of being his wife? Did your years with him influence your view of Ernest (especially in light of their troubled father-son relationship) or of Mary?

VH: Greg was an enchanting person. We spent a good part of four days together at the funeral. He was funny and clever. He was a startlingly good athlete and amazingly articulate. I knew nothing about him except that he had "gone bad," and that had no bearing on the person I met at his father’s funeral. The courtship was intense and a lot of fun. He was living in Boston then and I was in New York. It took several years of marriage before I realized how disturbed he was, and yet I still hoped. My years with Greg did not influence my view of Ernest because we simply did not discuss his father. Greg harbored great anger toward both his parents. The man I knew and the father he knew were two different entities. Just as Greg was not mentioned at the finca, Ernest was not discussed in our home. I would say that my view of Mary did not change because of my marriage to Greg. I have always judged people on personal experience. Greg resented Mary. Therefore anything he had to tell me about her was biased. I was not influenced by his opinion.

JMG: After your many struggles with Greg, including his transvestitism, what was the ultimate last straw that led to your divorce? Was the postscript that deals with Greg in the initial draft of Running with the Bulls, or did you add it later?

VH: Greg filed for divorce, not I. I realized he was sick and in need of medical help. If he could have received that help, he stood a chance of achieving something in life. When he realized what I was trying to do, he filed for divorce.

The postscript was not in the initial draft. Since Greg’s death was a matter of public record, I was advised to mention it and record my reaction. The final three pages of the book are a condensed version of a eulogy I gave for Greg at the Hemingway Society International conference in Stresa, Italy, in 2002.

JMG: You have held a variety of positions in journalism and publishing. How was tackling a memoir of your own life different from working with the words of others? Was there a single aspect of this book that you found the most challenging? The most exhilarating?

VH: Working with one’s own words is both harder and easier than working with the words of others. Harder because you have to sit and create, to impose discipline and adhere to a schedule whether the muse is willing or not. Easier because there are no restraints, no misunderstandings. There is freedom and pride in accomplishment. What I found most challenging was trying to sort out and condense a vast amount of material–the highlights of almost sixty years–to produce a coherent and flowing story. I know exactly how exciting or harrowing parts of my life have been. Would I be able to convey those emotions to the reader with only words? The most exhilarating aspect of writing was reliving those wonderful early years and realizing for the first time how exceptionally lucky I was to have lived such a life.

JMG: At the conclusion of the book, you say, "This is my time to speak" (page 291). What made you decide that the moment had come to share your story? Did you find it difficult to break your silence?

VH: Over the years I had refused to be interviewed on the subject of Hemingway or the Hemingways. Gradually, biographers invented a persona for me. When Picasso painted Gertrude Stein’s portrait, she said to him, "That doesn’t resemble me." He replied, "It will." Such also is the power of the written word. I came to the conclusion that if I wanted to correct my image before it was cemented, I would have to tell the story in my own words. When news of Greg’s tragic death was splashed in the tabloids and regular press, I was deluged with requests for interviews. I felt that, rather than continue to hide, I should speak out. I intended to end the book with our divorce. It was not easy for me to write about personal matters. I would rather report someone else’s tale. Now I am glad I have done it. I have been amazed at the positive response. I receive letters daily from people who have been touched by some aspect of my story.