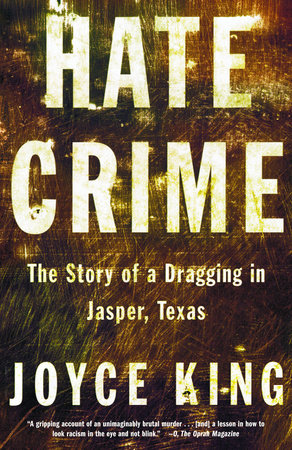

Author Q&A

A Q&A with Joyce King, author of Hate Crime

Q. HATE CRIME tells the horrific, yet captivating story of the dragging death of James Byrd, Jr. in 1998. Tell me what has changed over the last 4 years since this crime took place?

A. This question has answers on several levels. First, in Jasper itself, I believe a hard lesson has been learned. A lot of residents thought such an idyllic little community could never have provided the location for such an unspeakable crime. They thought race relations were okay, but discovered a lot of people are still consumed by the past.

Second, at the state level, the Byrd murder was a catalyst of sorts to reignite a much-avoided discussion on hate-crime legislation. Reborn as The James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Act, Governor Rick Perry, a Republican, signed the bill into law in May 2001. That’s a huge change, especially when you consider his predecessor, George W. Bush, refused to support the measure as it was written. It took six years to push this legislation through. I believe this horrible crime, and the justice served afterward, promoted more positive racial dialogue that made it a little easier to get the conservative support necessary to win its passage.

And finally, on a national and international level, our world has changed dramatically in the last four years, particularly in the past year. Sadly, Americans are learning, as other world citizens understand, that hatred is powerful. Whether it is hatred for a man because his skin color is different, or, hatred of a nation because viewpoints are not the same, the outcome can be painfully similar: Hatred hurts all.

Q. Being from the south, you know firsthand what the racial climate is like. Have things changed for the better or for the worse since the crime was committed? Since the trial?

A. Since the June ’98 dragging, some things feel as if they’re never going to change. Racial progress can sometimes produce a Catch-22 atmosphere–with the remarkable progress of the Civil Rights Movement, and the inclusion of the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday as testamonials. But there is also that undercurrent of “unfinished business” that will require an honest dialogue. I believe this national communication might render blacks and whites more kin than is comfortable. Since the last trial, I think the justice delivered in this case may have fueled an ever-present hope that it’s not too late to go back and provide closure in cases, (because of the explosive timeframe) justice was absent. Certainly, things are better today, but we all have a long way to go. Blacks and whites are in a marriage, that God, in a humor constantly challenged, has forever bound together. No manmade power can separate us.

Q. What could you tell us about meeting the 3 offenders face-to-face?

A. Perhaps the most chilling vis-a-vis encounters with the accused occurred the first time I saw John William King being escorted, shackled across the courthouse lawn. Nothing had prepared me for such a polite-looking hatred. Day after day in the three separate trials of King, Brewer, and Berry, the most difficult thing was hearing gruesome testimony and being able to reach out and touch those responsible. I was told not to even bother trying to get a jailhouse interview with King since he’d never subject himself to answer questions “from a black woman.” People were always asking me about the mindset of the trio, and what made them click. Those same people were always disappointed at the lack of depth, intelligence, and education the defendants possessed, or didn’t. If these young men were such superior criminals, why were they captured less than 24 hours after the crime? There was no “mastermind” at work here. Beyond the three culprits, it was Shawn Berry’s brother, Louis, who gave me my greatest insight into their beer-and-backroads lifestyle. In our one-hour chat, (as the jury deliberated his brother’s guilt or innocence) I learned that Louis was very interchangeable with Shawn. They were one and the same.

Q. Tell me more about the insight Louis gave you.

A. Louis really told me some personal things about the clique of friends that included King, Brewer, Shawn, himself, Tommy Faulk, and a handful of others. They all had similar country-boy personalities–lived too hard, too fast, and liked drinking beer together. There wasn’t a whole lot to do in Jasper on the weekends. Yet, Louis was also, as I say in book, “tragically poetic.” There was something very sweet about him, but also something that might be a little dangerous.

Q. You describe what the George Beto Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice looks like as you drive up and go inside, you also describe the high security. Do you think the prison system is a major contributor to the events that led to the tragedy? What do you think can be done to change it?

A. I don’t believe the prison system, per se, is a major contributor to the events that specifically led to June 7th. However, like several components in this case, it did play a role, just as another common denominator that link the three men. All were high school dropouts. Coincidence? I don’t think so. But does prison need more improvements? Definitely. One change that would require little cash involves educating the public. In my research, I discovered that most people don’t have a clue about life in prison and how it can shape racial attitudes. Some inmates are able to drop survivor beliefs adopted in prison once released. Others, like King and Brewer, never sucessfully let it go when they are deposited back into the "free world." We must be careful to not allow the prison system in this country to shoulder all the blame for the ongoing racial strife that exists, or the racist gangs that organize there, and are on the rise. Prison does not begin to explain, or account for racial crimes committed in the workplace, on college campuses, or at places of worship by people who have never been locked up! Everyone in prison, from warden to inmate, talked about a lack of respect. That’s also the key in the free world as well.

Q. What made you think to place yourself, the narrator, in the story and were you worried that it wouldn’t work?

A. Initially, I started writing with myself as the storyteller only, but all the passion in me was saying, "How can I possibly ignore the way I feel about this case and the impact it has had on me?" With that as a starting point, I was never afraid that it wouldn’t work. I was, and am confident that when given their chance, the reading public will not only see themselves in the ordinary working person I am, but they will also be able to relate this experience to extraordinary circumstances we all face in life, and how we choose to rise to meet those challenges. I didn’t happen to Jasper; it happened to me.

Q. What did you hope to accomplish by writing HATE CRIME?

A. What I hoped to accomplish when I began this journey at the end of 1999, after the third trial, was to have world citizens, literally, walk a country mile in my shoes. To see this incredibly small town, nestled away in these thick woods, among a history of racial violence perpetrated, mostly, against black men. I wanted to accomplish the connection that blacks and whites have so much more in common, than not. At the same time, I didn’t want to paint a rosy, all-is-racially-healed portrait that would’ve given the impression that racism in East Texas has been cured. Justice was never denied, nor delayed in this case, which must, somehow be viewed as a model for those larger cities that remain unsuccessful in the delivery of justice. I think this book accomplishes what I hoped–to give brave Jasperites who did take a stand vindication. After all, the town didn’t drag James Byrd, Jr. Three young white men did.