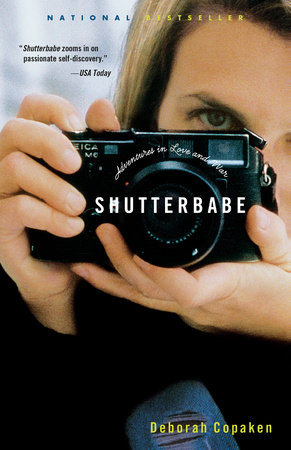

Shutterbabe Reader’s Guide

By Deborah Copaken

1. This memoir begins with the loss of an egg (menstruation) in a minefield and ends with the birth of a child at home. Discuss the metamorphosis of the author’s conceptions of motherhood.

2. Often our knowledge about news events is shaped by the media’s portrayal of these events. At one point the author laments, after a photo of her climbing a Soviet tank is splashed across the front pages of newspapers, “Nobody wants to hear the truth when the myth is so much better.” Discuss the differences between the myths propagated by the media and realities the author saw in Israel (rock-throwing by the Palestinian children), Afghanistan (the mujehaddin yelling “Down with America!”), Holland (the quiet of the street versus the wire reports), Zimbabwe (a human life taken in the name of conservation), Romania (particularly the orphan photos), the former Soviet Union (the tank photo, the West’s embrace of perestroika versus the everyday reality of Soviet life), and even corporate America’s public lip service to family-friendly policies.

3. How do you think the author’s experiences with random everyday violence influence her choice of career. What about her subsequent abandonment of this career?

4. Examine the following statement from chapter five: “Whatever else we might choose to discuss, eventually it all comes back to either sex or the Holocaust.” What do you think this means?

5. How does the author’s Jewish identity affect her actions and thoughts? In the fourth chapter, the author discusses the Hebrew word for love, ahavah, which is etymologically related to the word for giving, hav. How are Judaic notions of love and charity woven throughout the book?

6. Each chapter in this book is named after a male of some significance in the author’s life. Three are lovers, one’s a good Samaritan, one’s her husband, one’s her son. Could this book have been written without the personal stories intertwined? Why do you think the author–an independent woman, crisscrossing the globe on her own–chose to title her chapters in such a way? What did each of these men teach her? What did she, in turn, teach them? Why do you think she dedicated the book to her daughter?

7. Seeking companionship, understanding, a connection with others is one of our most basic human drives. But opening oneself up emotionally, like covering wars, is also dangerous. It makes us vulnerable. The French have this concept imbedded in their language: aventure can mean either “love affair” or “adventure.” Discuss this parallel as it pertains to both the author’s relationships and her work as a photojournalist.

8. Throughout the ages, men have tried to control women and their bodies. Discuss this statement with regard to the author’s experiences both abroad (particularly in Afghanistan and Zimbabwe) and at home (particularly with regard to rape and assault.) Now take it further. How are all of the following things related: chastity belts, female genital mutilation, veils/headscarves/burkas, foot binding, high heels, workplace discrimination, sexual harassment, catcalls, spousal abuse, rape? Can you think of others?

9. Western art, more often than not, involves men gazing at women. What happens when women gaze at men? Do we accept the frank female gaze or try to crush it? What does the way you critique this book say about you, your sense of morality, your acceptance or rejection of the female gaze? How does your gender and/or sexual identity affect the way you read this book? How does your age, religious beliefs, marital status, education or upbringing affect it?

10. The author notes that all of her early heroes–Virginia Woolf, Diane Arbus, Sylvia Plath–committed suicide. Compare the prose of Woolf, the photos of Arbus, the poetry of Plath. How do the different forms of their self-expression nevertheless offer some similar themes? How much of their psychology do you think was self-propelled and how much was influenced by the mores and values of the historical period into which each was born? Would a Woolf, an Arbus or a Plath born at the end of the twentieth century be less likely to commit suicide or not?

11. The word “slut” has no male counterpart. Neither does the word “mistress.” How does gender-biased language affect out ideas about behavior?

12. How will this book alter the way you look at a photograph in a magazine now, if at all?

13. Is the embrace of family and its concomitant responsibilities an abandonment of feminism or an acceptance of biological reality? Why are many of the difficult choices faced by women–to abort or not, to “act like a man” or not, to marry or not, to procreate or not, to work outside the home or not–so fraught and politically charged that, whatever choices a woman makes, she will be lambasted by one camp or another for making them?

14. What about the book’s title? Think about the double entendre: “babe” meaning “naïve”; “babe” as an appropriation of male language. Do you think the title works as an ironic conceit, or does it undercut the book’s message?

15. How and why is humor used in this book? Is it ever inappropriately used? How do you deal with pain?

16. Would this book have been better served if the author had transformed her experiences into fiction? Why or why not?

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In