Author Q&A

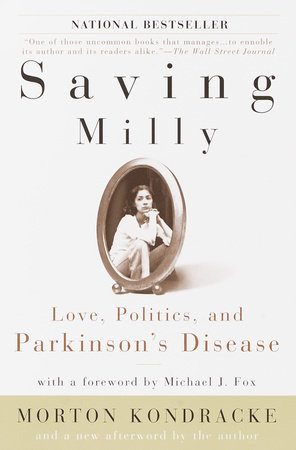

A Conversation with Morton Kondracke

Fred Barnes is executive editor of The Weekly Standard, and Morton

Kondracke’s co-host on the Fox News Channel political show The Beltway

Boys.

Fred Barnes: What was Milly’s reaction to your book?

Morton Kondracke: Milly read the chapters as they were being

written, then I read it to her right after the book came out, and

again recently. The best thing she said was, "This is a great

love story." The first time she read the last chapter she said it

depressed her. It is sad. It’s about death and about losing Milly.

FB: What effect did the book have on Milly?

MK: The book helped change the ending, I think. Partly because

of the hoopla connected with the book–the praise it

got, the publicity, having her picture on the front page of USA

Today, and the hundreds of letters we received–she was encouraged

to get a feeding tube. I think Milly, being the indomitable

person she is, probably would have decided to stay

alive under any circumstances. But the book has made her life

more exciting.

FB: Do you have any regrets about revealing intimate details

of your marriage with utmost candor?

MK: I don’t. I didn’t reveal every intimate detail about our marriage

or what the illness involves, about what Milly can’t do

now and what I do to help her. I did tell a lot because I figured

this was the only biography that would ever be written about

either of us, so I should tell as much of the truth as I could

about our lives. And I wanted people to understand in detail

what a wretched disease Parkinson’s is so they’d help us fight

for a cure.

FB: While writing the book, did you ever pause and think,

"Maybe I shouldn’t be revealing this"?

MK: There were a couple of minor things that my daughters,

Alexandra and Andrea, asked me to take out and I did.

FB: What did Alexandra and Andrea think about the book?

And what effect did it have on your family?

MK: They are very proud of me for having written it and

happy about its success. It’s helped draw us even closer together.

Friends threw two wonderful book parties in Washington.

At one of them, both of my daughters spoke very

movingly of their love and admiration for Milly–about what a

strong mother she is and how much courage she’s shown.

They said that ours was the best marriage they’d ever encountered

or could imagine. They were both eloquent. I was very

proud of them. They say they learned things from the book

about Milly’s upbringing that they hadn’t focused on, though I

don’t think they were surprised by anything. Right before the

book came out, Alex found boxes of old home movies we’d

taken and prepared a video that was played on television a

couple of times when I was interviewed. She said she learned

from those movies what a stylish, "hip" person Milly was in the

old days.

FB: If you could write the book again, are there things you’d

put in that you didn’t?

MK: One thing for sure. Members of Milly’s foster family in

Chicago were deeply hurt by the implication that they were

not only poor, but didn’t keep their house clean. And also by

the impression that Milly’s childhood was totally miserable.

Neither is correct, and I’d try to make it clear that they

scrubbed a lot. But their house was old and it had bedbugs that

couldn’t be cleaned away–hence the use of DDT that Milly

thinks triggered her Parkinson’s. Also, though her mother

abandoned her and her father died when she was young, I tried

to say that she was raised by a wonderful family, the Villarreals,

who gave her great values and inner strength. Milly feels nothing

but gratitude toward them, and so do I. So I’d write more

about good times in her childhood.

FB: Your book got some phenomenal reviews and sold well.

Was this what you expected? Were there any disappointments?

MK: I had so much favorable feedback from friends before the

book came out that I hoped it would be well received. What

happened was beyond all my expectations–some amazingly

laudatory reviews and a lot of publicity that happened partly because

President Bush’s decision was pending on federal funding

of embryonic stem cell research. Saving Milly made it onto two

national bestseller lists. And the mail has not stopped, especially

from people sharing their own experiences with chronic illness.

Of course, once you get a taste of success like this, you don’t

know the limits and you lose your objectivity. So you hope that

maybe you’ve written another Tuesdays with Morrie, and there’s a

letdown when you realize you haven’t. I was disappointed by

a few friends in the media who I thought would pay attention

to the book and didn’t. And I thought that Oprah Winfrey

would–not make this an "Oprah book," but let me talk about it

on her TV show because it is a story about love and commitment.

But basically I’m gratified by the response.

FB: You’ve said that both psychotherapy and your religious

faith helped you handle Milly’s illness. Did they conflict or

complement each other?

MK: No, they didn’t conflict. I suppose some psychotherapists

see religion as too rigid and absolute and some religious people

think therapy means "whatever makes you happy." But as I’ve

experienced therapy and faith, they’re entirely compatible. Religion

is all about ends and ultimate things–your relationship

to the greatest power in the universe and whether you’ve enlisted

in the army that fights for Truth, Goodness, Beauty, and

Love. Psychotherapy is more about means–improving your

capacity for love, openness, and generosity. I think a good

therapist can be an angel, doing God’s work. Mine, Dr. Dorree

Lynn, is. And her message is strikingly similar to that of your

and my spiritual adviser, Jerry Leachman, who preaches out of

the Bible the importance of having a grateful heart–realizing

that all you have is a gift from God. Dorree, when I’m inclined

to dismiss the good things in my life and concentrate on what I

don’t have, tells me that’s sacrilegious. The two of them are entirely

in sync and I’m happy for it.

FB: Why did you need psychotherapy in the first place?

MK: I have a natural tendency to be moderately depressed.

I wasn’t very trusting, was closed to other people and self-absorbed,

narcissistic and judgmental. Maybe you can pray your

way out of such things, but I think God’s answer would be to

send a friend or a therapist to help you. I’ve had both–a therapist

who helped me name and work out my psychological bad

habits, and generous friends who taught me how to be more

generous. In Milly, I’ve had both a therapist and a friend. I can’t

say I’m fully where I ought to be even yet. Everything is a

work-in-progress.

FB: Why did you need your Christian faith?

MK: I’ve always believed in God and I was brought up in the

Christian tradition. Milly’s illness has made me more dependent

on God–utterly dependent, in fact. I say "God, I need

your help" about twenty times a day. And He does help me.

The important process for me now is trying to mature as a

Christian. As I wrote in the book, I believe completely in Jesus’

message. I’m studying his message and his life more deeply, but

I still don’t have the same connection that I feel with God.

FB: Some of your friends, including me, believe you were

too hard on yourself in describing "the old Mort" as self-centered

and snobbish before Milly’s illness. What do you

say about that?

MK: I don’t think I was a monster, but I certainly had chronic

flaws. I may have played them up to contrast myself with

Milly, who was and is the opposite of all I was–generous,

forthright, utterly democratic and unimpressed by status, and

pretty fearless. I may have emphasized my weaknesses to underline

her strengths, but I didn’t distort anything.

FB: Your old friend, Michael Kinsley, the editor of

Slate.com, revealed in Time magazine last December that he

has Parkinson’s and said he chose "denial" as a strategy,

telling very few people and continuing his life as usual. You

and Milly chose what he calls "confrontation." Why?

MK: I’ve known Michael Kinsley for twenty-five years. He was

my editor at The New Republic. I’d learned from others a few

years ago that he had Parkinson’s. I was relieved when he

stopped keeping it secret. Psychologically, Milly and I did try

to practice denial for about a year. We didn’t conceal her tentative

diagnosis, but we did try to deny it to ourselves and try to

find an alternative diagnosis. Milly is such an up-front person

that she doesn’t have much capacity for secrecy and deception.

She didn’t tell her psychotherapy clients right away, but she

did tell everyone else. I followed her lead. If it had been up to

me, or if it had been my illness, I might have opted for a third

option Kinsley describes–acceptance. But Milly’s distress was

so great that I couldn’t do that. And I don’t have much capacity

for secrecy and deception, either. Kinsley disparages what he

calls "aggressive victimhood," which he says is socially trendy.

Michael is such a contrarian and ironist that whatever society

favors is what he won’t do. But aggressive victims and their

families are indispensable in getting more research money for

Parkinson’s and other diseases. So I hope now that Michael

Kinsley will join us.

FB: You’ve lobbied the White House and Congress for more

funding for medical research. You almost lost your press credentials.

How did you resolve this dispute?

MK: I resolved it by obeying the rules of the congressional

press galleries and giving up the chairmanship of a group called

NIH2. It was moribund anyway, and the cause of doubling the

NIH budget was succeeding, so obeying the ethics police was

easy. On the larger issue, "should journalists ever lobby?" I agree

in principle that they shouldn’t. On the other hand, I don’t regret

what I did. I thought my wife’s life was on the line and I

had to do whatever I could. Parkinson’s disease research is still

deeply underfunded, and lobbying Congress to change that

is still necessary. I don’t do it myself, but I help the Parkinson’s

Action Network do so and I speak out at every opportunity,

which is within the rules.

FB: Milly receives medical treatment at the National Institutes

of Health free of charge while you continue to campaign for

doubling the NIH’s budget. Isn’t there a conflict of interest

there?

MK: I don’t feel any conflict at all. I would support doubling

NIH’s budget even if Milly weren’t receiving care

there. And Milly’s been willing to be a guinea pig whenever

NIH has asked her to join in a clinical trial. I acknowledge

we have received far more from NIH than we’ve given back. If

it were legally possible for me to pay for her care there, I

would. Or, my insurance would. And, I’ve been critical of

NIH, too, especially its reluctance to a fight an all-out war on

Parkinson’s.

FB: Why does it do that?

MK: It is determined not to "play favorites" among diseases,

even though NIH itself says that Parkinson’s is the most curable

of all neurodegenerative diseases.

FB: How has the political community responded to the effort

to double NIH’s budget?

MK: Pretty well. The initial impetus for doing this came from

Congress, particularly from Senators Tom Harkin of Iowa and

Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, among those currently in office.

Increases of 13, 14, or 15 percent have been approved for four

years, a pace that would produce a doubling over five or six

years. The Bush administration supports doubling over five years,

but Bush is playing favorites on behalf of cancer and, of course,

bioterrorism research. The big question is, "What happens

next?" If we return to increases of 5 percent or less per year–

which I fear Bush’s budget people favor–it will be a disaster,

like hitting the brakes on a fast-moving vehicle. Labs will have

to close, projects will be stopped, and people will get fired.

Disease cures will be delayed. A lot of thought needs to be

given to what happens after doubling.

FB: You argued that President Bush should permit broad use

of stem cell research on so-called "leftover" embryos at fertilization

clinics. How do you feel about "cloning," or creating

fertilized embryos for research purposes? Any doubts about

that?

MK: Actually, I am torn about the cloning issue. I’m definitely

against cloning to produce babies, which has all kinds of "brave

new world" implications, as well as being dangerous. In animals,

many clones have terrible birth defects. On the other

hand, so-called "therapeutic cloning" has great advantages.

People could contribute cells from their own bodies, have embryos

cloned, and use the resulting stem cells to repair defective

parts without tissue-rejection problems. But, there is a

slippery slope problem here: if it’s okay to create embryos and

extract stem cells when they are five or six days old, why not

let them grow five or six months and "farm" fetuses for hearts

and other body organs–also to save lives? Frankly, I hope this

moral dilemma can be avoided by the success of research on

adult stem cells derived from blood, marrow, or even fat cells

and require no cloning. If I were in Congress, I guess I’d vote

to allow therapeutic cloning, but limit research to days-old

embryos.

FB: Why does it take celebrities such as you and Michael J.

Fox to stir public interest in a disease such as Parkinson’s?

MK: We live in a publicity-minded culture and celebrities attract

more publicity than anyone else–especially if they are as

legitimately beloved as Michael J. Fox and Muhammad Ali are.

Members of Congress are close to the most publicity-minded

group in America, always looking for witnesses who’ll attract

TV cameras to their hearings and attention to themselves. But

celebrity hasn’t been enough to win the fight for adequate

Parkinson’s money, at least not yet. What it really takes is a

powerful politician who is dedicated to the cause.

FB: Has the warfare among disease groups for federal money

persisted?

MK: No, the fact that the NIH budget is doubling has significantly

reduced the competition. In fact, the major disease

groups have collaborated wonderfully in this common effort.

But the competition will start again if, God forbid, the budgets

begin to go flat again. Nobody will say openly "Cut cancer and

give to us" or "Cut AIDS," but they will be inclined to stop cooperating

and just go for themselves.

FB: Do you plan another book?

MK: I think there is a useful book to be written about

dysfunction–you might say, civil war–in the American

health system. We have the best health care in the world, but it

is much less good than it could be, largely because cost pressures

are threatening quality. Everybody’s fighting–doctors

against insurance companies and HMOs, hospitals with their

own nurses, malpractice lawyers with all providers, the government

with drug companies. Through Medicare and Medicaid,

the government sets prices for most medical procedures and

the process is horribly inefficient. And then there’s the growing

problem of the uninsured, who often don’t get attention until

they are sick enough to go to an emergency room. All this

could be described in a compelling way, and I have some ideas

about solutions. I think health care will be back as a major national

issue and perhaps I could help the process.

FB: So you’d go from Saving Milly to Saving Health Care?

MK: I’m looking for a better title, thanks.