Author Q&A

Q: Amid the current battles over faith and religion, there appears to be a silent majority of people who don’t align themselves either with the fundamentalists or the atheists, who don’t know quite what to believe about their faith. Your book gives a reasoned and passionate voice to this group; was that your intention?

A: It certainly was my hope. So many books about faith—and many written by really intelligent people—take a single line: “You’re crazy if you have faith” or, “You’re crazy if you don’t have faith.” I marvel at their surety. I’ve always experienced faith as a mystery, when I had it, and now that I don’t. But I have no assurance that I’m right in my thinking or that I’m even close to an answer about belief. I just know in retrospect how wonderful it was to have faith, and that I can’t fake having it when it’s not there. I suspect there are many people with my dilemma, and I hope that my experience will be useful to them as they struggle with their own changing faith, or its loss. And I hope as well that people of faith who read this will be understanding of friends who grapple with belief.

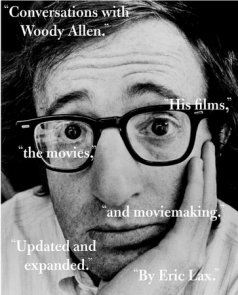

Q: You are perhaps best known for your books on film stars like Woody Allen and Humphrey Bogart. What made you want to write your own story? And why now?

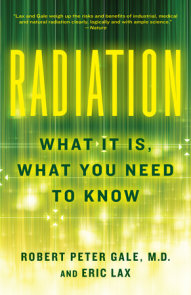

A: I’ve also written about life on a bone marrow transplantation ward, and the development of penicillin, so I like a lot of different topics. I’ve been thinking about this book for at least 10 years. I’ve long been curious about how people come to faith, how they keep it or lose it, and how they use it for good or ill. An omnibus book about faith didn’t appeal to me (nor do I have the scholarship to write one). As I thought more about the subject, I realized that my own story, intertwined with those of my father, an Episcopal priest, and my college roommate George Packard, whose youthful faith mirrored my own, might be a way to examine the subject in a way that would be enjoyable for me to write and also draw readers into a story that would prompt them to consider their own faith as well. As for why write it now, I’m at a point in life—my mid-sixties—where if you aren’t thinking about God and faith and what happens next, you’re not paying attention. As there are no definite answers to these questions, I knew the book had to be short.

Q: In writing Faith, Interrupted you went back through piles of old letters and documents. Was it at all difficult to relive your past so closely?

A: First, I was astonished that I had saved so many letters. My teens through my thirties are quite fully documented by letters I sent to my parents, and those they sent to me, as well as dozens to and from friends. Of course, it was a sobering experience to literally run into the person I was 40 years ago. Some of the stuff I read made me cringe, but then some of it made me feel I was a reasonably thoughtful guy. But it wasn’t difficult to go through the letters—although there were times that memories good and bad flooded in—so much as it was enlightening. For instance, I had long felt that I didn’t tell my parents very much when I was in the Peace Corps and was grappling so intently with being a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War on grounds of religious training and belief. Then I discovered that my most coherent writing about it was to them. Without the letters, I don’t think I could have written this book. I would have had to come at it another way, because I would have had to rely on memory, which we tend to shape to our purposes over the years, instead of being able to draw on the actual feelings and descriptions of the time.

Q: As you mentioned, there are two men whose stories are closely tied to your own faith journey, the first being your father. What kind of influence did your father have on you when you were growing up?

A: My father was a monumental influence on me. He was very funny, not the first thing you associate with a priest, and he had a great understanding of and sympathy for human nature. So although he was very devoted in his faith, he was not rigid. That doesn’t mean he didn’t strictly adhere to the teachings of the Church, but he understood and practiced forgiveness, and held love as the central tenet of Christianity. I was an acolyte from age 6 and was as comfortable in church as I was at home; being in church with my dad was like visiting him in his office. I learned my practice of faith by his example, just as I learned the value and enjoyment of humor through his jokes, puns, and shaggy dog stories.

Q: You write that you started losing your connection with religion after your father’s death. How do you think he would have reacted to your “interruption” of faith?

A: I like to think he would have accepted and perhaps even admired the honesty of it—and then would have prayed very hard that I find my way back to the Church.

Q: The other man whose life you chronicle is your friend George Packard or “Skip.” Why did the direction his life took become so important to you?

A: Skip and I were much alike in our faith as college students. We both were acolytes from an early age and we both were active in the college chapel. Then Skip’s army experiences—many officers considered him the best leader of an ambush and patrol platoon—and mine in the Peace Corps were so dissimilar that our lives were no longer parallel. After the army Skip entered seminary and in the years following, his faith grew in ways much different and deeper than my own. But because we started at more or less the same place, he has been a natural touchstone for me, and the direction his life in faith has taken is what for a long time I thought mine might be.

Q: Do you ever wish that you followed the path that Skip did and had become an Episcopal priest?

A: My father always said that you don’t decide to become a priest; you answer a call from God to become one. There were times in my teens and twenties when I thought I heard at least the first rings of that call, but it never was strong enough for me to answer it. So, no, I don’t wish that I had followed Skip’s path, although under different circumstances, it would have been interesting if I had.

Q: Can you tell us more about what led you to take the position of a Conscientious Objector during the Vietnam War?

A: In the months leading up to my graduation from Hobart College in 1966, the scale of the war in Vietnam increased greatly and it was clear that the draft awaited pretty much everyone who didn’t have a deferral for graduate school. From the start of my senior year I had given thought to whether I was a CO and if so, what was I willing to risk? I concluded that my religious training and belief taught me that killing was wrong, and I had the support of the Episcopal Church, which had long honored such a stance. I rejected the option to be a non-combatant medic because I felt that whatever I did would only support the war and put soldiers back in a position to do what I was opposed to. By declaring myself a CO I was not evading the draft. I believed I could be called to serve the country and was happy to do that in any capacity outside the military. I was born in Canada and could have gone there, but I wanted to work within the law as a citizen and take the consequences. If that meant going to prison in lieu of being drafted, were my CO denied, I would do it, and I told that to my draft board.

Q: Looking back a little earlier, do you think that you would have joined the Peace Corps if not for the Vietnam War?

A: Yes. The Peace Corps ideally suited my talents and needs. I was drawn to the idea of service, and I didn’t have much of an idea of what I wanted as a career. I wasn’t looking to take an advanced degree in English or go to law school, so it was a great way to do something responsible and gain time to come to a decision about what I wanted to be. Without the Peace Corps, I don’t know that I would have ended up a writer. The Peace Corps was also the perfect choice for someone who didn’t want to be drafted. So in all honesty, joining served two ends.

Q: Are there other memoirs that you’ve read that inspired your own work?

A: Memoirs are a lot like Tolstoy’s description in Anna Karenina of unhappy families—each is distinctive in its own way, though in the case of memoirs, they don’t have to be unhappy. The point is, every memoir is unique to the person telling it, and so the story and how it’s told are unique as well.

Q: What was the most important thing that you learned about yourself through the writing of this book?

A: In tracing the path of my spiritual progress (or regression), I was able to understand how I’ve come to where I am in a way I did not know before. One of the biggest questions most people have to answer is where we stand in our faith. Whatever the degree to which we believe or disbelieve, we have to honestly face our deepest feelings, reservations, and doubts. I think only then can we find our way to meaningful faith, or accept that we have none. And in that self-examination I came to realize that the foundation of the faith I had, articulated again and again by my father—that the heart of it is to love one another—has not disappeared, even if that foundation no longer is “religious.”