Excerpts

Prepare an Arab Feast with Reem Assil

The James Beard Award semifinalist and owner of Reem’s California on eating and cooking as an Arab in America.

The following is an excerpt from Arabiyya by Reem Assil, This cookbook is a collection of 100+ bright, bold recipes influenced by the vibrant flavors and convivial culture of the Arab world, filled with moving personal essays on food, family, and identity and mixed with a pinch of California cool.

The Arab Table

By the time I reached my teens, a typical weeknight meal featured a hodgepodge of dishes passed back and forth across our table: spiced rice and vermicelli with stewed green bean loubieh leftovers, perhaps supplemented by last-minute vegetable chow mein Chinese takeout (halal to please my father) and General Tso’s chicken in sweet spicy sauce (to please us kids).

My mother, a grad student, would rush in from a forty-five-minute commute and then whip together dinner to head off the pending state-of-hangry threatening her home. The nightly news, turned up a little too loud, would sedate my dad in the next room, where he dozed after work. I would be pacing my room, guessing at my physics assignments to avert my father’s offers of help (he always took too long). And my sister Dalyah would hang out with her best friend, Elissa, the unofficial fourth Assil sister. My baby sister, Manal, would cling to our mother’s side, still acclimating to after-school care. It took a small miracle to get us all to the table.

The Arab table, for me, begins with my mother, Iman Kishawi. Today, she is a scientist with a Ph.D. and a twenty-year career working on the human genome project, proving it’s never too late to return to your passion.

But it wasn’t always that way. After a brief courtship, my parents married and made a hurried exit from Beirut, where civil war raged on the streets outside, and came to America, where my father landed his first engineering job. My mother jokes that if someone had arrived at her doorstep offering to move her to the North Pole, she would have gone immediately.

Instead, she landed in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where she discovered the ultimate American delicacy, peanut butter, and jelly, to the detriment of her waistline. She consumed these confections along with her first introduction to American culture: the daytime soap opera General Hospital and its incredulous adventures of Luke and Laura, who died and came back to life, reuniting in their love for one another several times. In place of bombs, F-16 fighter jets, and the hum of urban life, horse-drawn buggies pulled Amish families from farm to town. To say she felt shell-shocked would be too ironic.

Where my grandmother was extravagant, sliding plates over one another until the table overflowed with vegetables, preserves, pickles, cheeses, and spreads, my mother was ultra-practical, packing vegetables, grains, and meat into masterful one-pot meals.

Nutrition and flavor ruled my mother’s kitchen; impressing guests was lower on her list. She knew how to layer spices and aromatics into stews like Shorbat Freekeh, a rich smoky concoction of cracked green wheat, that even to this day, tastes like home each time I take my first bite.

When we moved to Sudbury, a small suburb of Boston, our table expanded to feed more than just my mother and father. The Arab table became a calling for her to nourish those she loved. If we came home asking why we weren’t doing taco Tuesday like the rest of the kids, my mother would sauté some ground meat in tomato sauce, spiked with Arab seven-spice mix, spoon it into tortillas, and voilà, it became Arab taco night. She kept her pantry stocked to feed family members who were passing through, whether on their way to begin university studies or nursing heartbreak.

After playing this role for half a decade, my mother decided she had been at home long enough. She overcame my father’s reluctance, convincing him that our family needed two incomes. She wanted to be a scientist and set about resuming her studies at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. As part of her Ph.D. program, my mother took a research job at the laboratories of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Every day, no matter what else might have been happening, she would dash out the door to feed her lab cells. We joked that she cared more about her cells than her kids.

With my mother’s daily departure, we became latchkey kids, raised on afternoon TV, including Saved by the Bell and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. The cupboards soon filled with instant ramen, mac and cheese, and giant square pizzas from Sam’s Club. Dinner became a grab-and-go affair, and we rarely ate at the same time. For us, the comforts and tradition of the Arab table were overcome by the demands of working parenthood in America.

I missed the years when our home was a bed and breakfast for uncles and cousins who filled our table with Arabic and laughter. I began to long for the times when our aunts lavished us with family meals on our trips to Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine. There, no matter the hardships, the family gathered each day: men returned from work, food flooded the table, and everyone sat together at mealtime. Despite the economic and political instability all around them, there was a sense of connectedness at those tables that I loved.

In America, we had stability but no table. The Arabic phrase we use to call family to the table for the first meal of the day, khalleena nitrawwa’, means “let’s relax.” Here, we’d shake cereal from a box and dash out the door to school. There was no tirwaa’a (in other words, no leisurely breakfast), no fetching fresh falafel from the street corner to add to the mosaic of small plates, stacked with fruits and vegetables and spread with olive oil-coated labneh and cheeses.

My mother, too, struggled with these contradictions. She had arrived in this country with a master’s degree in microbiology, only to take up a post in the kitchen, when, in fact, she did not even know how to cook. She deferred her professional ambitions for eight years to fulfill family and social expectations as a wife and mother. It was nearly impossible to do everything well all the time, and yet our freezer full of fatayer proved her determination to try.

While she had less time for meals, she still remained vigilant against blows that scraped away at our identities. Protecting us from the hardships of being Arab in America sometimes meant taking matters into her own hands. In middle school, two older boys often waited at the end of the block, ready to pepper me with insults and threats on my daily walk to school. I’d bow my head and pick up my pace, until I felt safe enough to catch my breath. One day, one of the boys taunted me, “Go back to Arabic.” I answered in the same nonsense way, “Go back to Italian.” That day, I had come home crying one time too many, and my mother marched down the street to confront one of the boys. With a few choice words, issued at very close range, and a handful of his shirt in her grip, the bullying stopped. No one ever braved a second encounter with my mother.

One day, I returned home from school in tears. Our social studies unit on cultures of the world had screened a film from the 1970s about Arabs that depicted an Arab family around the dinner table. In place of the invocation yislamu idayk—“God bless your hands”—murmured almost reflexively by everyone I knew to celebrate the cook, the film’s dramatic climax hinged on Arabs burping to show appreciation. As my classmates laughed, I felt shame and embarrassment.

The next day, my mother stormed the school and demanded that they establish an alternate lesson plan; however, there wasn’t an existing one that depicted Arabs as we really are. So, she made one herself and volunteered to teach it. At the end of the month of Ramadan, our month of fasting, she came to the school as a guest speaker and shared ma’amoul, our special nut-or-date-stuffed cookies with a delicate melt-in-your-mouth semolina crust pressed into decorative molds. Every year thereafter, she found a way to arrive at school with sweets and teach a lesson about Arab culture.

Her ferocity wasn’t reserved just for our battles. She fought to be recognized even in everyday transactions. I cannot count the number of times she confronted store clerks who heard her accent and made the mistake of underestimating her. “Do you think I’m clueless just because I have an accent?” she would say, while disputing even small matters at the register. We’d try to play it down, embarrassed by her escalations. But in hindsight, I realize she was demonstrating what it means to stand up for yourself.

I get my courage from my mother. She’s not a diplomat; she’s an advocate. She wanted to protect us from forces that would cause us to question our worth. Education was our ticket to financial independence, and she made sure we had the best. Throughout my life, I have witnessed my mother stand by the side of women dealing with abusive husbands, fighting unsuccessful battles against cancer, and standing up to unfair conditions in their workplaces. But she struggled in her own household to get support from all of us to keep our house in order.

She wasn’t as religious as my father, but she felt constant pressure to enforce his strict rules, telling us we couldn’t go places or do things that she might have thought were okay. She had little time to herself, and when tensions erupted, she’d dash out of the house and escape alone to a theater to watch whatever happened to be on screen.

In my search for purpose, I have returned again and again to the Arab table as a place that shapes my identity.

The Arab table, for me, is a place of contradiction. The table I create in my adulthood resists patriarchy and concedes to a nurturing maternal impulse. It can feel good, generous, even spiritual to cook for others. And it can feel oppressive when it’s expected of me.

Ironically, when I finally found my way to the kitchen, I confronted an industry dominated by white men. Like my mother, I made it my mission to set my own terms. But it hasn’t been easy.

Still, I’m excited to raise a feminist child and to demonstrate that family, to me, is larger than just my household: it’s my co-workers, community, friends, and comrades, struggling just like me. I’ve stationed my Arab table at the crossroads of my many communities.

MA‘LOUBA ∙

Spiced Rice Tower, Layered with Caramelized Veggies

Makes 8 to 10 servings as the main event

MA‘LOUBA IS A layered Palestinian rice dish; its name means “upside down” in Arabic. Flipping the pot to reveal its contents is the moment of truth. Will it stand upright, revealing a tower of rice layered with mosaics of vegetables? If not, just remember the first spoonful will send it cascading into the serving tray anyway.

No two ma‘loubas are alike. While I was growing up, we had it Gazan-style with eggplant and lamb. In California, Palestinians from the West Bank insist that chicken and carrots make the ultimate ma‘louba. While disputes rage on the best proteins and veggies from village to village, family to family even, devotion to this dish unites all Palestinians, both within Palestine and in the diaspora.

I’ve opted for a version of this dish that places vegetables in the star role. You can use just about any vegetable. I’ve offered a fairly traditional method of preparation, but there are several ways to simplify this dish. It may seem like a lot of frying, but it goes quickly, and it’s the best way to get the caramelized flavor we’re looking for. And if you fry hot enough, your veggies shouldn’t feel or taste oily at all.

TIP • If you prefer not to fry, toss the vegetables in neutral cooking oil, such as sunflower or canola, add a sprinkle of salt, and roast at 425 degrees F until sizzling and golden brown, about 30 minutes.

1 ½ cups basmati rice

1 large globe eggplant, sliced into ¼-inch rounds (about 1 pound)

2 tablespoons kosher salt

2 cups neutral oil, such as sunflower or canola

½ cup cornstarch

1 russet potato with skin, sliced into ¼-inch rounds

2 large carrots, cut on the bias into ¼-inch rounds (about 2 cups)

1 head cauliflower, broken into 1 ½-inch florets (about 4 cups)

2 red bell peppers or 3 or 4 small mixed bell peppers, sliced into ¼-inch strips

Cooking Liquid

4 cups water or vegetable stock, plus more as needed

2 tablespoons Seven-Spice Mix (recipe follows)

1 teaspoon ground turmeric

2 teaspoons kosher salt, plus more as needed

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper, plus more as needed

Neutral oil, such as sunflower or canola, for greasing

2 Roma tomatoes, sliced into ¼ -inch rounds

4 garlic cloves, thinly sliced

¼ cup slivered almonds, toasted

¼ cup chopped parsley

2 cups plain whole-milk yogurt or Yogurt, Mint, and Cucumber Salad (recipe follows) for serving

Rinse the rice and soak for 30 minutes. Drain well.

Meanwhile, sprinkle the eggplant with 1 tablespoon of the salt and set aside for 5 minutes to release some of its water (and some bitterness along with it).

Line two sheet trays with paper towels.

Pour the oil into a large pan, until the oil is deep enough to immerse a layer of the vegetables, about 2 inches, and warm over medium-high heat. The oil is the right temperature if the vegetables sizzle and swim around immediately and slowly brown while cooking. If using an instant-read thermometer, heat the oil to 350 degrees F.

Place the cornstarch in a shallow bowl. Pat the rounds of eggplant dry with a paper towel, coat both sides in cornstarch, and gently lower them into the oil, filling a single layer. Fry in batches until golden, about a minute on each side. Set the rounds on the prepared sheet trays to drain.

Fry the potato, a single layer at a time, until brown. The potato rounds should be lightly golden and about halfway cooked; set aside to drain.

Fry the carrots, a single layer at a time, until the surface bubbles and browns slightly; set aside to drain.

Fry the cauliflower, a single layer at a time, until the florets are crispy and brown; set aside to drain.

Fry the bell peppers, a single layer at a time, until they curl and brown; set aside to drain. The carrots, cauliflower, and bell peppers need to take on a browned color but stay al dente.

Use the remaining 1 tablespoon salt to season the vegetables after they’re fried.

To prepare the cooking liquid: Add the water to a small pot and bring to a simmer. Add the spice mix, turmeric, salt, and black pepper and maintain a simmer.

When ready to assemble, brush the bottom and sides of a large straight-sided pot (a 3-quart Dutch oven works great) with oil. In concentric circles, layer half the eggplant, carrots, potato, tomatoes, bell peppers, and cauliflower, in that order. Sprinkle half of the rice on the first vegetable layer. Repeat the layering with the second round of vegetables and sprinkle the remaining rice on top. Scatter the garlic across the top.

Gently pour in the spiced stock, taking care not to disturb the vegetables and rice; you want to keep the layers intact. Add more water if necessary to ensure the rice is at least ½ inch below the waterline. Over medium heat, return the pot to a simmer, taking care not to reach a vigorous boil, which might displace the layering. Turn down the heat to low, place a heavy plate smaller than the pot as a weight on top to keep the layered rice tower compact, and cover with a tightly fitted lid. Cook for 30 to 45 minutes or until the rice is fully cooked.

Turn off the heat and let the pot rest for 10 to 15 minutes, then remove the lid and plate and cover the pot with a large flat-bottomed platter. Using oven mitts, sandwich the pot with one hand on the platter and the other beneath the bottom and quickly flip the pot upside down so it rests on the platter.

Now comes a little luck and superstition: thump the bottom of the pot with the base of your palm or a wooden spoon and give the rice a few minutes to slide down to the platter. Carefully jimmy the pot directly upward and, if all goes well, the rice and vegetables will retain the shape of the pot to form a layered tower.

Sprinkle with the almonds and parsley. Serve warm with a side of plain yogurt or with the yogurt-cucumber salad.

KHYAR BIL LABAN ∙

Yogurt, Mint, and Cucumber Salad

Makes 4 to 6 servings

I LOVE WHIPPING up this salad with crunchy chunks of cucumber, a little garlic zing, and enough yogurt to have some left over as a condiment. It goes with just about everything.

Each element contributes a cooling effect, creating a nice balance with Arab food’s warming spices, a relationship that I imagine might trace back to Ayurvedic practices and Indian raita, which is prepared in much the same way. Arabs love eating this salad with rice or meat dishes. After a long day, I sometimes wonder, is there anything better than a hearty bowl of Mujaddarra, topped with this salad?

Since khyar bi laban is eaten with Arab meals mostly as a condiment, the portions are fairly small. It can also serve as a condiment for sandwich fillings like Kafta and Shawarma Mexiciyya.

4 unpeeled Persian cucumbers

2 or 3 garlic cloves

1 teaspoon kosher salt, plus more as needed

1 cup whole milk yogurt

1 tablespoon dried mint

½ cup chopped mint leaves (about 5 sprigs), plus more for garnish

1 tablespoon lemon juice (about ½ lemon)

1 teaspoon lemon zest (optional)

Cut the cucumbers lengthwise into sixths and then chop them into ¼-inch pieces.

Mince the garlic with the salt on a cutting board, until it releases its liquid or mash in a mortar and pestle until a paste forms.

Combine the cucumbers and garlic with the yogurt, dried mint, mint leaves, and lemon juice and zest in a serving bowl. Adjust the salt to taste. Garnish with additional chopped mint leaves.

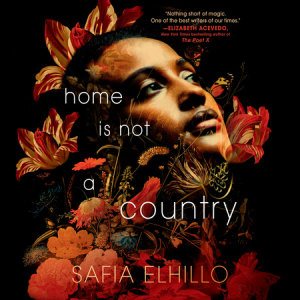

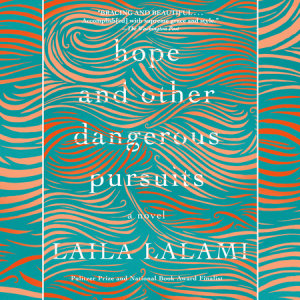

Audiobooks of Arab Stories to Listen to While Cooking

MUSAKHAN ∙

Sumac-Spiced Chicken Wraps

Makes 16 mini wraps or 4 full wraps

MUSAKHAN IS PERHAPS the most iconic of all Palestinian chicken dishes. I often joke that while we don’t have a nation-state, we most certainly have a national dish. Extravagant and communal, the chicken is traditionally served whole, steeped in olive oil and reddish-purple sumac. It is mounded over caramelized onions atop a hearth-baked flatbread called taboon and soaked with the cooking juices. People sit around a table, using bite-size pieces of the bread to tear off bites of chicken.

I didn’t grow up eating it that way. Ever. My mother, like lots of Arab mothers in the United States, adapted the chicken-onion combo into tortilla rolls. Eating this wrap with sumac and onion juices drizzling down your arms is part of the experience and a sign of a good juicy braise.

It’s equally great at room temperature and can be served as a party appetizer wrap.

This home recipe is adapted from my restaurant’s most popular wrap called the Pali-Cali, since it brings together Palestinian musakhan with arugula, producing something deeply satisfying and easier for non-Arabic speakers to pronounce. I like to add avocado for some extra California love. I think my family in Gaza would approve.

1 pound skinless, boneless chicken thighs (about 4 thighs)

2 ½ teaspoons kosher salt, plus more as needed

3 tablespoons sumac

½ teaspoon Seven-Spice Mix (recipe follows) or ground allspice

5 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil, plus more for drizzling

6 cups thinly sliced onions (about 2 onions)

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper, plus more as needed

1 tablespoon pomegranate molasses

4 pieces Saj Bread or your favorite brand of 12-inch flour tortillas

4 cups trimmed arugula

½ cup pomegranate seeds (optional)

1 avocado, sliced (optional)

In a medium bowl, rub the chicken thighs with 1 teaspoon of the salt, 2 tablespoons of the sumac, and the spice mix and let them sit for 2 hours at room temperature or refrigerate overnight.

Preheat the oven to 300 degrees F.

In a medium pan, heat 3 tablespoons of the oil over medium-high heat. Add the onions and ½ teaspoon of the salt and sauté until the onions are soft and translucent and slightly browned.

Transfer 1 cup of the onions to an 8 by 8-inch baking dish and set aside.

Continue to caramelize the remaining onions on low heat.

Arrange the seasoned chicken in a single layer over the onions in the baking dish and drizzle with the remaining 2 tablespoons oil. Cover the pan tightly with aluminum foil and bake until the chicken is cooked through and breaks apart easily with a fork, 55 to 65 minutes.

While the chicken is baking, continue to caramelize the onions on low heat, stirring often, until they’re very soft and deep golden brown, 20 to 25 minutes. It’s important to cook the onions slowly to reduce their liquid and bring out the sweetness. Remove the pan from the heat, add the remaining 1 tablespoon sumac, the remaining 1 teaspoon salt, and the pepper and drizzle with the molasses. Adjust the salt and pepper to taste. Let cool slightly.

Using two forks, pull apart the cooked chicken into bite-size shreds and fold the caramelized onion mixture into the cooked chicken.

Lay out the flatbreads on a dry work surface and distribute the pulled chicken and onion mixture in a nice straight line down the center of each bread. Top with the arugula, pomegranate seeds, and avocado. Fold in the sides and roll up each flatbread, burrito-style, going from the bottom to the top. Drizzle the flatbreads with a little oil and give them a quick toast in a cast-iron skillet or heavy pan for some color.

Serve whole as a meal or sliced into quarters for the perfect party bite.

The rolls can be stored covered or in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to 3 days and reheated or enjoyed at room temperature.

SABA’A BAHARAT ∙

Seven-Spice Mix

Makes ¼ cup

THE MIXTURE IN baharat, which literally means “spices” in Arabic, varies from region to region and family to family in the Arab world. In the Levant, baharat is most commonly prepared as a seven-spice mix that relies on warming spices tempered by woody flavors like cumin and coriander. The spice is so foundational to stews, meats, and rice dishes that, while every family has its own recipe, it seldom needs to be written down. If you equip yourself with only one spice mix to make the recipes in this book, this would be it. I use this spice mix as a base for much of my cooking and layer on other spices as needed.

This recipe can easily be doubled or tripled and stays fresh for a month when stored in an airtight container. If you multiply the recipe, it’s better to toast the spices one at a time to ensure each has sufficient access to the surface of the pan.

TIP • If you don’t have all the spices in your pantry to make the seven-spice mix, you can omit the cloves and cardamom to make a five-spice mix for recipes that call for seven-spice.

1 tablespoon whole allspice

1 tablespoon whole cumin seeds

1 tablespoon whole coriander seeds

9 cardamom pods

1-inch piece cinnamon stick

½ tablespoon whole cloves

½-inch piece nutmeg, crushed

Combine all of the spices in a small pan and toast over medium heat until warm and fragrant. The spices should start to gain the slightest color, have a noticeable fragrance, and begin to make a faint crackling sound. I gently touch the spices with the palm of my hand. They should be hot but not burn you. Do not let them smoke. If that happens, you’ve gone too far, and you’ll need to toss them and start fresh. The whole process should take 2 to 3 minutes.

The spices can go straight from the pan to the bowl of a spice grinder, but be sure to allow a minute or two for them to cool, uncovered, before grinding to avoid condensation. Then pulse in a grinder or high-powered blender until coarsely ground. A coffee grinder works well, too. Just make sure to wipe or run a spoonful of rice through it afterward to clean the cup.

Reprinted with permission from Arabiyya: Recipes from the Life of an Arab in Diaspora by Reem Assil, copyright © 2022. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Photographs copyright © 2022 by Alanna Hale. Illustrations copyright © 2022 by Cece Carpio.

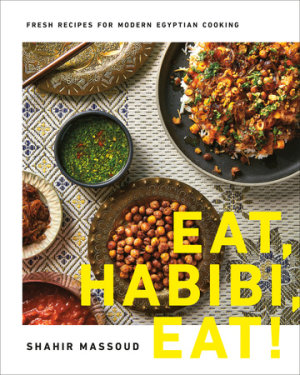

Keep Exploring Arab Flavors with These Cookbooks