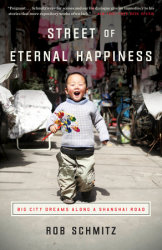

Rob Schmitz, China correspondent for American Public Media’s Marketplace, first immersed himself in China back in 1996 as a Peace Corps Volunteer in rural Sichuan province – and the country hasn’t let go of him since. As APM correspondent, he has reported on a range of topics illustrating China’s role in the global economy, including trade, politics, the environment, education, and labor. Now, the Edward R. Murrow Award-winning journalist opens up to an even wider version of his experience in China with his first book, Street of Eternal Happiness: Big City Dreams Along a Shanghai Road. After reading the book, we had some follow-up questions for Rob.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: What is the single biggest difference between China today and the China you first came to know twenty years ago, when you’d arrived there with the Peace Corps?

ROB SCHMITZ: Money. Since I arrived as a Peace Corps Volunteer in 1996, the pace of China’s economic growth has been unparalleled. Before the turn of the century, most Chinese still lived in rural areas and farmed for a living. Now, hundreds of millions have moved to the cities and they’re working a wide range of jobs in a much more diversified economy. This rapid pace of growth and the accumulation of wealth has had a profound impact on everyday Chinese, and I wanted to capture how they coped with such change.

PRH:You write about the various people you came to know as an expat living in China. Generally, did you find that you were accepted as an American living there? What was the overall Chinese opinion of American and Americans in the late 1990s when you were there with the Peace Corps? Has that general consensus changed over the last two decades?

RS: The people I’ve come to know and write about along my street are very curious about America, and that’s something that hasn’t changed since I first came twenty years ago. What’s different today is that some of my characters have actually visited – and lived in – America. The youngest people in my book speak very good English, and their lives are becoming increasingly global. More Chinese are traveling to New York, Paris, Sydney, and they now own homes in Los Angeles, Vancouver, London. They are now our neighbors, and from the standpoint of an average American, they know more about our country than we do about theirs.

PRH:You write quite a bit about Xi Jinping’s Chinese Dream, which essentially is this government-promoted idea that an individual’s goals in life should match up directly with China’s national goals. Is it true that this idea has become quite divisive? What is it that draws people to it? And pushes them from it?

RS: In order for the Chinese Dream to be divisive, people in China would first have to give it serious consideration. I don’t think that’s happened. I see propaganda posters up and down my street promoting the Chinese Dream, but like most propaganda is in China, they’re largely ignored. That’s not to say that most Chinese aren’t patriotic. Typically they are, and many Chinese believe the campaigns Xi Jinping is waging – especially the campaign against corruption – are needed to ensure a better future for China. But as far as dreams go, individual Chinese – much like people everywhere – possess their own dreams, and they’re more intensely personal than a collective dream for the motherland.

PRH:I was stunned by the stories of Maggie Lane. The block’s residents have been, in recent years, forcefully ejected from their homes (quite often violently so) and kept away until those homes are levelled to the ground, along with the residents’ possessions, leaving them homeless. This is allowable as the Chinese government owns all property in China, correct? Do you see this changing anytime soon?

RS: The state owns all the land in China. That said, seizing land the way the local government took Maggie Lane – by abducting residents without any warning and then abruptly bulldozing their homes – is illegal under current Chinese law. That doesn’t mean these residents could hope for a fair trial, because China’s legal system is controlled by the Communist Party and, of course, favors the Party in legal disputes. That said, I do see changes on the horizon that will ensure residents have stronger rights to the land their homes sit on. But I think the reason for this is a government that is increasingly worried about how land seizures are impacting social stability.

PRH:Speaking of required relocation, it was announced this week that the Chinese government will relocate two million people from rural backcountry to urban environments this year, to be followed by an additional eight million people over the next four years. In spite of the greater access these people will have to better public resources – namely, healthcare and education – this immediately puts forth a bevy of potential pitfalls. What do you think of this plan? Will it succeed? Is it a terrible idea? Is it the wrong way to lift people from poverty?

RS: I think it depends on whether these new urban residents will have jobs waiting for them in the city. The government’s urbanization campaign is coming at a time of slowing economic growth, and jobs are becoming harder to find. The other concern is whether China’s city governments are prepared for this influx of new, rural residents. I recently returned from Lintao, a city of nearly 200,000 people in Gansu province, which suddenly ran out of water after this year’s Lunar New Year festival. The reason wasn’t the terrible drought suffered by the region in recent years. Local government officials told me that drought was only part of the problem. The other part was pressure by the central government to relocate poor, rural residents into Lintao. They’d moved tens of thousands of people into high-rise apartments inside the city over the past year. More people means a greater need for resources such as water. And by February, they’d tapped out their groundwater.

PRH:In addition to being a challenge for trade, internet censorship in China puts forward a host of other issues. Do you foresee this changing anytime soon? Do you think it should?

RS: Foreigners and China’s English-speaking elite are certainly annoyed by China’s Internet censorship, because they can’t access many of their favorite foreign sites without the aid of a VPN (virtual private network). But most Chinese aren’t concerned about the issue, because nearly all the websites and social media apps they typically use are allowed inside the Great Firewall. That’s not to say they shouldn’t be worried about it. The Party’s control over information inside of China means young Chinese don’t have easy access to uncensored versions of history and news.

PRH:Street of Eternal Happiness approached your experience in China in such a unique way – through the stories of a number of Chinese individuals. Do you think you’ll write another book on China? If so, have you thought about the angle?

RS: I would love to write another book about China, but I’ve been too busy with my own reporting to give the matter any serious thought.

PRH:What is your absolute favorite thing about living in China?

RS: The people. I could sit and talk to people here for hours without getting bored. Their stories are fascinating, and their perseverance through difficult times inspires me.