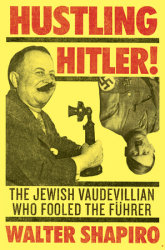

Acclaimed journalist Walter Shapiro always took the fantastical stories his father told him of his great-uncle Freeman Bernstein with a grain of salt. According to family legend, Freeman was a famed vaudevillian who had hustled Hitler and the Nazi government out of thirty-five tons of embargoed Canadian nickel, instead supplying them with endless amounts of scrap metal and tin. It wasn’t until after his father’s death that Shapiro looked in to Freeman’s history – and was astonished by what he found. Endless Variety columns, newspaper clippings, and Freeman’s own memoirs had been waiting to be discovered. Shapiro’s discovery culminated in Hustling Hitler, the story of how his great-uncle fooled the Fuhrer, dedicated to his father. Walter Shapiro sat down with Penguin Random House to discuss his great-uncle’s legacy, vaudeville, the importance of remembering, and more.

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE: Hustling Hitler is, of course, not historical fiction, but the way you construct each scene and get inside the minds of the major players in your book reads like it. Was it important to you that Hustling Hitler read like a narrative as opposed to a history book?

WALTER SHAPIRO: My theory with Hustling Hitler was that every anecdote and story had to either be fun or to illuminate character. I told myself that I wasn’t writing a Winston Churchill biography, so I was free to leave out the boring stuff. But mostly, my great-uncle Freeman Bernstein was such a flamboyant character and his hustles were so extraordinary that there wasn’t much about his life that was boring.

PRH: What gripped you most about Freeman Bernstein, apart from your father’s fondness of him? Was there something about him that ultimately made you want to write this book?

WS: Maybe beneath my political columnist veneer, I’m really a conman at heart. The family connection was part of the fascination, but much larger was the way that I became enraptured with Freeman Bernstein’s life as I learned more about him. Each story (from being a silent movie producer until the tragic insurance fire to running an Irish festival in Boston under the ludicrous name of Roger O’Ryan) was wilder than the last. So, ultimately — like the reader I hope — I was hooked by the story.

PRH: Hustling Hitler isn’t just about Freeman; it’s also about New York, the vaudeville scene, wartime, the American Dream, and much more. A tremendous amount of research must have gone into populating Freeman’s world with detail and atmosphere. How did you begin your research, and keep from being overwhelmed by the breadth of all that you were trying to bring back to life on the page?

WS: The research really began when I discovered at the New York Public Library a pamphlet Freeman had written in 1937 entitled, Was Hitler’s Nickel Hi-Jacked? Promising to offer “The STORY of the CENTURY,” the booklet claimed that Freeman had met with Adolf Hitler himself and the Fuhrer had spoken perfect English, a detail that has somehow been missed by historians.

Another great benefit was that the New York City Archives throws nothing out. So I discovered to my joy that two large boxes — containing all the DA’s files from Freeman’s indictment for scamming Hitler — had been saved in a warehouse in Brooklyn for the past seventy years. Also using federal government and the state of California archives, I assembled in total more than 1500 pages of government papers about Freeman’s quasi-legal activities.

My favorite was finding in the State Department archives a telegram that the U.S. consul in the Dominican Republic had sent to the FBI asking them to hold Freeman when his boat docked in New York. It seems that Mr. Bernstein had abandoned a vaudeville troupe in the Caribbean. The consul warned the Bureau not to believe any “suave story” that Freeman may tell “since he has a gift of making black look like white.”

PRH: Much of the book is devoted to Freeman’s time in vaudeville, as an agent to performers and managing theaters. Why do you think vaudeville was so popular at the time, and why did it fade away?

WS: How I wish I could have seen a night of vaudeville that Freeman produced in places like Bayonne and New Britain. I suspect that it combined the full range of show business — the talented, the desperate, the grizzled grease-painted veterans going through the motions. What killed vaudeville (and it was a long, slow, agonizing death from about 1915 to 1930) were the movies. And by the early 1920s, Freeman’s vaudeville-booking business had disappeared.

PRH: Freeman was a self-described hustler, and owed countless debts for much of his life, but there was also something inherently likable about him. A good amount of nostalgia permeates your writing about Freeman, but you also aren’t afraid to take a step back at times and tell it like it is. How would you characterize your relationship with your subject, Freeman Bernstein, while researching and writing Hustling Hitler?

WS: Freeman did not always behave in an exemplary fashion. It bothered me when he failed to honor his commitments — and stiffed actors and business associates. But Freeman was also generous when he had the money, which, alas, was too rarely to preserve his reputation for honesty. As much as he liked the good life (men’s fur coats, first-class shipboard cabins and hotel suites), he wanted much more to be part of the game, the action, the excitement of Times Square. That was a reason why Variety called him the “Pet of Broadway.”

PRH: The beating heart of Hustling Hitler lies in your efforts to reanimate Freeman’s life. In order to achieve this, you relied largely on censuses, newspaper blurbs, Variety’s extensive coverage of Freeman’s exploits, and Freeman’s own writing. But at times you needed to insert yourself into the book in order to connect the dots and speculate openly. Did you feel confident in your speculations because of how close you felt to your subject?

WS: Unlike most biographers, I wrote Hustling Hitler without the help of family papers, letters, or memoirs. Instead, I found about 2,500 newspaper clips on Freeman’s life and the lives of the people around him. That and the more than 1,500 pages of legal documents helped me reanimate the life of a man whom Variety called in its obit a “Fantastic Vaude Figure of Yesteryear.”

Sometimes I had the facts, but not the connective tissue to explain them. That was part of the reason why I felt necessary as an honest narrator to try to connect the dots for the reader.

I was very meticulous in explaining to the reader where I was forced to make shrewd guesses about what happened. In these cases, I outlined my reasoning either in the text or in the detailed Chapter Notes at the back of Hustling Hitler. Let me stress that all the quotes in the book and all the stories are verbatim — Freeman’s life was too rich and too wild to ever tamper with reality.

In writing Hustling Hitler I tried very carefully to avoid anachronisms in my use of the language. I repeatedly went to a variety of dictionaries (I used four major ones for the book) to check when a word or phrase was introduced into the language. I kept my cultural references within the proper period, as well. An example: I wanted to use some quotes from The Maltese Falcon early in the book. But I waited until a later chapter since the original Dashiell Hammett novel wasn’t published until 1930.

PRH: Why is it important to remember and tell the stories of those who came before us? Had you not uncovered Freeman’s history, he very well may have gone entirely unremembered – most people do. Did you consider it your responsibility to remember, and tell, his story? Did you write this book for your father, whose larger-than-life stories about Freeman you never believed in growing up? Did you also write it for Freeman himself?

WS: Freeman would have certainly gone unremembered. Since he left behind no children and only a few memories cherished by my late father and a few other now-dead relatives, there was no one else but me to lift the torch. But I am not a big believer in family genealogy, so it wasn’t as if I were writing the equivalent of a monograph about an obscure Civil War colonel who happened to be related to me.

I told the story in this book because it was just too good to leave buried in a nearly unmarked grave, which is sadly where Freeman lies in Los Angeles. Ultimately, I guess I wrote for myself because I was having so much fun discovering the details of Freeman’s life story. Though how I would love to have seen my father’s face as he read Hustling Hitler.

PRH: Although the book is titled Hustling Hitler, we don’t get to Freeman’s hustling of the Fuhrer until the final few chapters. As a Jewish man, Freeman tried to spin his actions as political, but only after the fact. To what extent do you think Freeman felt a connection with his Jewish roots?

WS: If I miraculously had been granted an hour with Freeman, that would be one of the questions that I would have asked. Freeman, who was born in Troy, New York, and spoke unaccented English, was independent enough to marry a showgirl, May Ward, who wasn’t Jewish. But he also arranged to be married by an Orthodox rabbi, which may either have been to honor his parents or because the rabbi, without a congregation, was willing to work cheap.

After Freeman’s parents (my great grandparents) both died in 1920, he took a side trip on a visit to Europe to visit the ancestral home in what is now Poland. Probably most of the relatives he visited died in the Holocaust. But when Freeman returned to New York, he gave a shipboard interview to the Yiddish newspaper Der Tog on the plight of European Jews wishing to emigrate.

As for hustling Hitler, Freeman and his partner in Toronto (also Jewish) were out to make a killing on bogus Canadian nickel. If they could hustle the Nazis, so much the better. But, to be honest, they would have also conned the Dutch if the money were good. So I guess the idea that the victim was Hitler was a side benefit rather than the purpose of the nickel swindle.

PRH: Much of Freeman’s identity was wrapped up in his ability to craft a story and sway public opinion with props, flashiness, and the quick turn of a phrase. You’ve covered nine presidential elections and were a speech writer for President Jimmy Carter in 1979, so you, too, know a little something about the power that the right words can have. With that in mind, what do you think Freeman would have to say about the 2016 presidential election, and the current state of public discourse?

WS: Actually, I’m now covering my tenth presidential race as a columnist for Roll Call. Freeman was never very political, even though he tried to make a movie in 1916 boosting Woodrow Wilson’s reelection, which, if it had been made, would have been the first campaign commercial in history. And, of course, there was that Yiddish pamphlet he produced to help elect Herbert Hoover (yes, that Herbert Hoover) in 1928.

I think what would have appealed to Freeman were Donald Trump’s huge crowds. Whenever that many people gathered anywhere, Freeman would have figured there was coin to be had. And if they were gullible enough to support Trump (much as he dreamed of scamming the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s), he really saw a money-making opportunity. Actually, the more that I think about it, Freeman probably would have set up a phony Super PAC purportedly to support Trump – and then pocketed the proceeds himself.