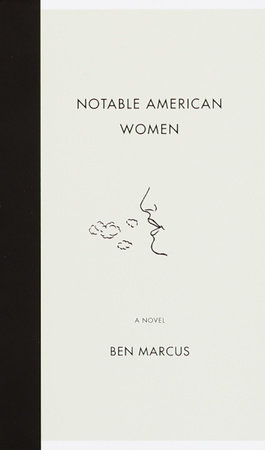

Notable American Women

By Ben Marcus

By Ben Marcus

By Ben Marcus

By Ben Marcus

Part of Vintage Contemporaries

Part of Vintage Contemporaries

Category: Literary Fiction

Category: Literary Fiction

-

$20.00

Mar 19, 2002 | ISBN 9780375713781

-

Dec 18, 2007 | ISBN 9780307427052

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Earthly Possessions

Out of This World

The Voice Is All

The Reef

The Second Plane

The Ways of White Folks

The Pioneers

House of Meetings

The Romance of Tristan and Iseult

Praise

"Ben Marcus has been accused of redesigning the ordinary sentence, of emptying words of their meaning and injecting them with new, of treating grave matters (such as family and humankind in general) with farcical disrespect, and of blowing away traditional narrative structures with a diabolical wind. And all this may be true. But for those who would describe this work as fantastic, surreal, or anti-real, I can only say that this is Ohio exactly as I remember it. Jane Dark was my fourth grade teacher." —Robert Coover

"Notable American Women is a weird nougat of a book that suggests Coetzee, Kafka, Beckett, Barthelme, O’Brien, Orwell, Paley, Borges—and none of them exactly. Finally you just have to chew it for its own private juice." —Padgett Powell

"Ben Marcus’s Notable American Women is a radical performance in American fiction. It is too literary for the novel as it is now practiced and consumed, and too perverse for other plausible designations. In order to pioneer the Marcus life-project the writer provides a ferocious handbook which, followed to the letter, launches a permanent revolution of nothingness. A family of unprecedented personae—the Marcuses, aided on the distaff side by Jane Dark, her listeners and Silentists—are brought forth to insure the evolution of "a new category." The writer "fathers" an extensive formal vocabulary to advance the Behavior Bible’s annihilating goals, including uncomely devices and strategies like the fainting tank, the thought rag, the shushing posture, along with an array of essential life-project products such as the Ben Marcus Locater Bell, Chew Stand, Apology Center, Thompson Waterô, etc. It is killingly funny, and creepily sad. This book represents an unmediated thrusting toward love with an arsenal of intellectual alienation, and just as forcefully, a thrusting toward alienation with an arsenal of brotherly love–depending upon where you are poised to withstand the cataclysm. It is a profound and profane description of our basest drive: fear. Notable American Women is the work of a retiring albeit twisted virtuoso. Not for the pusillanimous reader." —C. D. Wright

"Ben Marcus has created an innovative and unflinching portrait of the turmoil of the human condition, providing the reader a most rare gift: something truly new. Notable American Women contains strains of Donald Antrim and Samuel Beckett but is beholden to neither; it is a brave, original book." —Myla Goldberg

"Notable American Women gives us, with great panache and in eerie detail, a world that is cruelly reasonable within the near-religious limitations of its weird laws and customs. It is a book as unique as it is wonderfully strange." —Gilbert Sorrentino

"Notable American Women is an enchanting and moving novel. Like Italo Calvino and Lewis Carrol, Ben Marcus reconfigures the world that we might see ourselves in a cultural and moral landscape that is disturbingly familiar, yet entirely new. As though granted a new beginning, Marcus renames the creatures of our world, questions who we are and who, as men and women, we might be. Notable American Women is a wonder book, pleasurable and provocative." —Maureen Howard

"Auden, who asked two things of an imagined world—that it be somehow like ours and somehow unlike—would be Ben Marcus’s ideal reader, yet even without the poet’s dire program, I am altogether taken by this hilarious and sexy alternative universe. Just imagine! it is all done with words instead of mirrors, so much more reliable and so much more heartbreaking. Thus Prospero enthralls his crew." —Richard Howard

"Ben Marcus’s novel is funny and touching and full of movement and sound, all of which is even more remarkable since the book itself is about stillnesses and The Silentists and Behavior Water and things you put in your mouth to keep you from speaking. Marcus investigates—with equal passion—the intricacies of a new mythology alongside the intimacies of a broken family. This is the kind of strange and beautiful book you just want to have around, to dip into again and again." —Aimee Bender

"I don’t use the word lightly, in fact, I don’t use it at all, but Ben Marcus is a genius, one of the most daring, funny, morally engaged and brilliant writers, someone whose work truly makes a difference in the world. His prose is, for me, awareness objectified—he makes the word new and thus the world." —George Saunders

"Marcus (The Age of Wire and String) has crafted a dystopian novel in the tradition of Brave New World and 1984, with an overlay of 21st-century irony and faux naïveté. Writing in off-kilter documentary-style prose laden with acronyms and neologisms, he often wanders into ponderous whimsicality, but stretches of the novel are inspired riffs on contemporary totems and anxieties. Ambitious and polished, if sometimes willfully opaque, this is an intriguing debut." —Publisher’s Weekly

"For another disturbing book about breeding, try Notable American Women by Ben Marcus, an allegory about a misdirected child-rearing experiment (a boy is raised to have no feelings) that makes for a stunning, strange and beautiful novel." —Esquire

"[Ben Marcus] constructs his narratives as an astronomer would a space telescope, so as to better observe and laugh at the earthly conventions of realism. . . . Imagine The World According to Garp as rewritten by Edward Gorey. . . . Marcus’s prose can spiral up and away into sublime nonsense." —Village Voice Literary Supplement

"Ben Marcus’s first novel Notable American Women is a beautifully strange and compelling family allegory—Midwest mum and dad raise their son to shun all emotions—rendered in language that seems imported from a universe of deepest feeling, of intellect, of poetry, and, in the end, of majestic heart."—Elle

"[A] darkly funny caricature of modern life."—Time Out New York

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In