-

$20.00

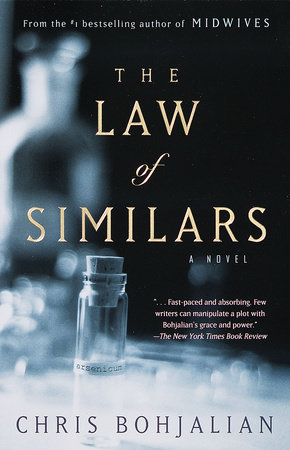

Published on Mar 14, 2000 | 336 Pages

Published on Mar 14, 2000 | 336 Pages

Author

Chris Bohjalian

CHRIS BOHJALIAN is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of twenty-five books, including his most recent The Jackal’s Mistress, as well as The Lioness, Hour of the Witch, Midwives, and The Flight Attendant, which has been made into a MAX limited series starring Kaley Cuoco. His other books include The Red Lotus, The Guest Room; Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands; The Sandcastle Girls; Skeletons at the Feast; and The Double Bind. His novels Secrets of Eden, Midwives, and Past the Bleachers were made into movies, and his work has been translated into more than thirty- five languages. He is also a playwright (Wingspan and Midwives). He lives in Vermont and can be found at chrisbohjalian.com or on Facebook, Instagram, X, TikTok, Litsy, and Goodreads.

Learn More about Chris Bohjalian