Mortals

By Norman Rush

By Norman Rush

By Norman Rush

By Norman Rush

Part of Vintage International

Part of Vintage International

Category: Literary Fiction

Category: Literary Fiction

-

$19.95

Jul 13, 2004 | ISBN 9780679737117

-

Mar 23, 2011 | ISBN 9780307789365

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

The Republic of Imagination

Immigrant Voices, Volume 2

The Procedure

Boy in the Twilight

The Jewish War

The Portable Hannah Arendt

The Power of Nonviolent Resistance

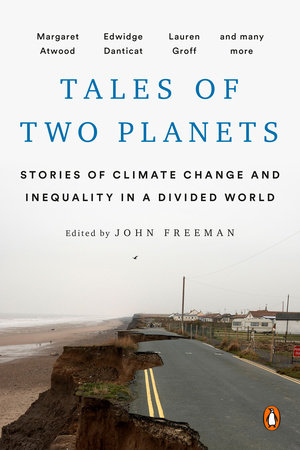

Tales of Two Planets

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

Praise

An astonishing accomplishment . . . [A] detonation of talent that threatens to incinerate competitors for miles around.” —The Christian Science Monitor

“Rush has now produced three books so full of brainwork, contour, sinew and laser light that we don’t want to leave home without him.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Wild and wonderful. . . . Whether the matter under scrutiny is marital wrangling or guerrilla rebellion, Rush’s observations are brutally accurate—and funny.” —The Seattle Times

“The depth and richness of Norman Rush’s second novel, Mortals, give him his own shelf in the canon”—New York Magazine

“Brilliant . . . Mortals is a deeply serious, deeply ambitious, deeply successful book. . . . Its central achievement has to be the fidelity with which it represents consciousness, the way in which it tracks the mind’s own language. . . . The two hundred or so pages in which Rush describes what is in effect a small African civil war seem to me some of the most extraordinary pages written by a contemporary American novelist.” —James Wood, The New Republic

“Remarkable . . . Rush [is] as challenging and surprising and uncompromising as ever.” —Time

“It’s no small feat to write engagingly about love, religion, philosophy, and war, and it’s no small feat to end up with something that dances on the line between earthy and stately. Each of [Mortals’] 715 pages is ripe with more ideas and insights than most authors try to get into a chapter. Mating was magnificent. Mortals, as hard as it is to believe, is even better.” —Fortune

“Psychologically acute, meticulously written [and] ambitious. . . . Should help console those still unreconciled to Graham Greene’s death.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Rush’s political wisdom, honed by the years he spent working in Africa, is enhanced by an acutely moral literary sensibility and his core humanity; together, the traits . . . imbue his work with depth and grace.” —The Boston Globe

“Complex and accomplished. . . . In both its wry-yet-forceful narrative style and its generous conceptual research, it is a worthy successor to [Mating].” —The Washington Post

“Few other books so powerfully convey the uneasy connection between intimacy and absurdity, the way that the minutiae of everyday domestic life can become so loaded with meaning . . . . Read it if you care at all about some very old, very vexed questions–about matters such as the knowledge of good and evil, or the nature of human wisdom and human folly.” —Houston Chronicle

“Broadens the scope of [Rush’s] fiction while going deeper into the human dynamic of a country in the midst of profound upheaval. Mortals envelops the reader in a manner that modern fiction too rarely attempts . . . no one caught in its sweep will want the experience to end.” —Chicago Sun-Times

“Bitterly funny. Mr. Rush has a canny understanding for Africa, a profound appreciation for the fine points of romantic love, a muscular style of description, and an eye for character so frighteningly sharp that it argues against running across the man at parties.” —The Economist

“The great joy in reading [Rush’s] work is that it seems to proceed from an unshakable belief in the capacity of the novel to embrace everything: global poltics, the nature of love, race relations, philosophy, religion, literature, the exact feeling of the dust in Botswana. . . . There is no denying its intellectual meatiness and its moments of intensity.” —Newsday

“A novel as ambitious and spell-binding as his first. . . . Rush weaves an astonishing array of subjects into his story, from Freud, religion and politics to life, death and Africa. Rush is a master of his characters’ minds. . . . Within [their] intense internal dialogues are thought-provoking, smart and often hilarious nuggets.” —The Baltimore Sun

“The sheer energy and ambition of Mortals seems to mock its creator’s earthbound status. . . . Reader[s] will be justly rewarded for persisting to the explosive climax that rips this novel’s civilized veneer wide open.” —The News & Observer (Raleigh)

“Breathtakingly ambitious. By the book’s end, Rush has given us masterful slices both of Africa’s indelible beauty and of its ongoing chaos. Rush is a real seer, and he captivates us with his audacious fictional vision.” —Elle

“A serious work that calls attention to the indissoluble link between the public and the private. . . . You’ll find it hard not to be impressed with the scope of Rush’s vision.” —The Miami Herald

“[Rush] is economical with language, choosing the best words to distill ideas and express them in gems . . . [He] has real affection for Botswana and its people. His rendering of the cadences of their speech is just right.” —St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“A masterwork of literary art . . . Mortals is a beautifully written, well-executed novel. It is written with passion, grace and flair. . . . Rush has a rare and beautiful gift of making readers feel true empathy for his characters. . . . A triumphant follow-up to Rush’s Mating.” —Fort Worth Star-Telegram

“Full of situations that range from subtly humorous to near slapstick that reveal an unusually keen human insight.” —The Denver Post

“Mortals is brilliant in its presentation of milieu, the heat, the squalor and the human misery of Botswana. The reader is immersed in an exotic culture and its political and social history rendered vivid by Rush’s prose.” —Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“Well worth the wait. . . . Rush’s prose, wit and insight provide so many delights. . . . Mortals should solidify his reputation and win him new readers.” —The Oregonian

“Wild and wonderful. . . . Rush inhabits the restless synchopative rhythms and associative bedlam of a male mind consumed by jealousy, disillusion and fading altruistic dreams. His observations are brutally accurate and funny.” —The Charlotte Observer

“[An] absorbing and variegated novel . . . effortless and riddled with surprises. . . . For readers hankering after a novel of ideas, it doesn’t get much better than this.” —The New York Observer

“The ideas are a brilliant bonus. The writing itself is intensely readable: not dry but juicy. It is rare for a novel of consciousness to be also a novel of action, but it is one of the distinctions of this book to be both.” —The San Diego Union-Tribune

“Lucid, luminous, proudly literary prose. . . . Makes the erudition of Rushdie or Frazen seem show-off frippery by comparison.” —The Village Voice

“Has the feeling of one of Evelyn Waugh’s satiric excursions into Africa. . . . The author’s keen intelligence and his experience of the multifariousness of Africa provide some generous rewards.” —San Jose Mercury News

“Brilliant . . . moving. Mr. Rush shows once again that he is one of the most intelligent and patient psychologists now writing fiction. The reader is not likely to find a better novel this year.” —The New York Sun

“Compellingly intelligent and intriguing . . . Hugely complex, deeply intelligent, engagingly garrulous.” —LA Weekly

“Rush’s latest delivers on his extravagant promise. Not only is Mortals every bit as rich and densely textured as its predecessor, but its thrillerlike plotting adds a whole new dimension.” —Time Out New York

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In