Author Q&A

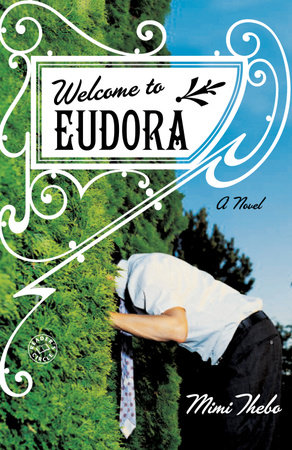

A CONVERSATION WITH MIMI THEBO

Mimi Thebo is from Lawrence, Kansas, but lives and writes in England. She is a Senior Teaching Fellow at Bath Spa University in England. Carrie Etter, a Bath Spa University colleague, is from Normal, Illinois, and is also currently writing about the Midwest. Mimi and Carrie had the following conversation about Welcome to Eudora.

Carrie Etter: First, I want to say how much I enjoyed reading the novel. I wasn’t far into it when I began thinking of people I wanted to recommend it to, especially friends who grew up or lived in small towns–Welcome to Eudora is full of sayings, gestures, and attitudes that I recognize from my own Midwestern upbringing. What experiences and ideas did you draw on to create Eudora?

Mimi Thebo: I think it’d be easier to say what experiences and ideas I didn’t draw on to create Eudora. I’ve been living abroad for much of my adult life, I’m still very much a Midwesterner. I can’t help converting, say, the price of a pork chop (and it doesn’t even come with vegetables), and for that price I could have a great meal with my whole family at Don’s Steak House and still buy a pint at the Free State Brewery!

CE: From the start, the novel moves briskly and buoyantly, and its voice made me think of your own charged energy and sense of humor. Do you see a relationship between the voice of Welcome to Eudora and your personal voice?

MT: I wish I was as clever as the narrative voice. It’s much more detached and objective than I am. When I’m in a social gathering, I’m always worried about what people are thinking of me, so much so that sometimes it’s hard to concentrate on what’s going on. But the Eudora narrative voice isn’t like that. It is secure and content. It knows its own place within this town, and it’s not solely that of a reporter; there’s a real warmth and affection in it. I want to be that voice when (and if) I grow up.

CE: I found the book very funny. Do you find small-town life a naturally humorous subject, or were you striving to make the portrait of Eudora especially lighthearted? Was the humor a part of a strategy for making sure the novel’s treatment of racial conflict doesn’t come across as heavy-handed?

MT: I can’t be serious about anything. I died for a little while when I was fourteen and since then, I have been been rather attached to the absurd. I don’t think it’s a defense against the dark side of life, or that I use it in narrative as a strategy to lighten the text. I mean, even really horrible things like war have many absurd moments. We’re the only beings we know who laugh, and we should do a lot more of it. It’s hard to shoot straight when you’re giggling like a fool.

CE: What would your ideal reader take away from this book?

MT: I think the main thing I’d want to put in my readers’ take-away boxes would be an understanding that divisions can be healed and that we all really do have similar values and desires. What we most need now in this world is people power– we’re being preyed upon by corporations and their political puppets. We all know we don’t want any part of it, but it’s hard to stand up by yourself and say no. It’s much easier, though, to reach out a hand to your neighbor. And when enough of us band together, we don’t have to stand up by ourselves anymore. We can stand together.

CE: Zadie and Doc Emery try to be independent of the community, but find themselves in situations where they need to work with others. Do you see this interdependence as a feature particular to–and a virtue of–small-town life?

MT: Oh, I used to just hateit when I was a kid. I mean, in a town like Eudora, you can sneeze alone in your bed at midnight, and by seven the next morning half the town will be recommending cold remedies. You’ve got no privacy. When I was in my twenties, I really loved the anonymity of a big city. But then I got a bit older and my priorities expanded and I started to be more concerned about my spiritual life than about my social life. My husband is a Zen student, and when I was writing this, linking karma with community was a bit of a no-brainer. If you really mess up in a town like London, you can move across town and change your job and avoid old friends fairly easily. But you can’t do that in a place like Eudora. People in Eudora never let you forget the time you kicked the football into the school incinerator, or kissed the wrong wife on New Year’s Eve. But the thing is, they’ll eventually forgive you. You won’t have to start a new life. You won’t have a fractured past. You’ll have the old one, and the mess will just be one part of it. I think that helps us spiritually. It is better for us in the long run . . . and it makes us happier.

CE: The story of the community–both of Eudora and of a larger national one–coming together to save the quarry seems to present “an ideal in action,” so readers can see how such a unity might be realized. Please tell us a little about the quarry’s role in the novel.

MT: Much of the recent history of the Midwest is a story of corporate abandonment. It’s not dissimilar to that of the coal miners in my husband’s native Yorkshire. Things can be done cheaper elsewhere, so jobs just go. The limestone quarry in Welcome to Eudora is a terrible employer. And I don’t think we think a lot about the economic dependency we have in places like this in our communities. Corporate interests are volatile, but we want our communities to be stable. Unless employers and workers have similar goals and values, you can wake up one morning and find that your town’s major employer has moved to the Szechwan Province, and that your house is now worth forty-five cents.

CE: This book clearly believes in people’s goodness and, partly as a consequence, in redemption. I wonder if you associate these qualities with small-town life.

MT: Every time I write about something, I end up writing about redemption/recovery. I’m just about ready to give up and admit that I don’t write about anything else. This comes, I think, again from my brief death at fourteen. I was in a car accident and fractured my larynx (which is why I sound like whiskey and late nights, even though I’m really about mineral water and in bed by ten). When I was in the accident, I was already in a terrible state. My folks were breaking up their seventeen-year marriage and my dad had just moved out. I was anorexic. Mom and I were broke, my grandmother was dying, and life sucked. Laryngeal fractures are rare. But that same day, there was another girl who was brought to the same emergency ward with that type of injury. She’d been riding her horse and hit a branch with her throat. She was fifteen, a barrel racer, from a stable family. She was a real athlete in prime shape, and her injuries weren’t as bad as mine. But she died, and I lived. I didn’t even want to live, and yet I was the one who recovered. I’ve always been fascinated by that. Always wondered, Why? And so I write about recovery because I’m continually looking at different models, probing them for answers to this question.

CE: Would it be right to say then that the residents of Eudora are so interdependent not just because they live in a small town–but rather, that such communities can arise anywhere where there’s a will, and the circumstances support it, because people are basically good?

MT: Absolutely. Right after I wrote the first draft of Eudora, I read a wonderful book by sociologist Robert Putnam called Bowling Alone. He talked a lot about “social capital” and how organizations can (but don’t necessarily) help create social capital. While I was reading this and his subsequent book, Better Together, I realized that Eudora was just dripping with social capital, and that this was its main strength. This kind of capital can be generated by any group of people, for any cause whatsoever. I’m sure a lot of reading groups have generated tons of social capital. I know churches that have gone on to do wonderful things with the fellowship they’ve generated in their congregations. Magazine publishers, computer companies, trade unions, PTAs . . . you can find examples of social capital wherever people strive for a common goal together. This kind of unity creates the people power that the world needs so desperately now. Friendship and trust radiate out from organizations that are successful in this way, and the people in them are truly able to change the world for the better. And as far as “circumstances” go, I think people make their own world in their own image. Social capital and the ability to work for the common good do not depend on where you live or what you have. They depend only on finding the things you have in common with your neighbor, and coming to terms with the differences. Once that’s done, the rest seems rather easy, whether it’s holding a bake sale to raise money for baseball uniforms, or petitioning to change government policy on oil exploration. We’re all interdependent. The whole planet is interdependent. Whether or not we can bear to think about it or look at our interdependence properly depends on how willing we are to do that “coming to terms with differences” thing. It’s not easy. Eudorans just happen to be pretty good at it.